Will Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III Make America White Again?

He and his supporters may have whitewashed his record, but the Alabama senator’s past statements and actions can be described in a single word: racist.

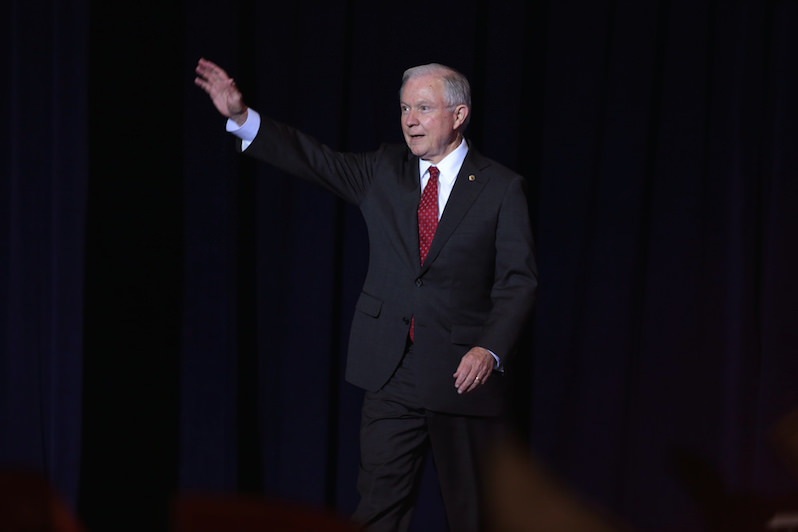

Jeff Sessions at a Donald Trump campaign rally at which Trump outlined a 10-point plan on immigration. The event took place in Phoenix in August. (Gage Skidmore / CC BY-SA 2.0)

President-elect Donald John Trump has named Sen. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, R-Ala., to be his attorney general.

Take a moment to let that sink in: If confirmed, Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III will become the nation’s top law enforcement official, in charge of overseeing the legality of federal programs ranging from immigration to national security and voting rights.

Ordinarily, I wouldn’t begin a column by highlighting the given name of a government appointee. I’d focus instead on policy. But Sessions is an exception—the rare case in which appellation, lineage and ideology intersect and overlap, illuminating the dangers of a nominee rather than obscuring them.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Sessions was christened after Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War, and Brig. Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, who resigned as the superintendent of West Point in 1861 to take command of the first Confederate army at Fort Sumter.

In his long career as a lawyer and legislator, the 69-year-old Sessions—who prefers the diminutive “Jeff”—has done much to make his namesakes proud. Like them, he’s made copious statements, taken actions and, in his instance, cast votes that can be described in a single word: racist.

Sessions graduated from the University of Alabama School of Law in 1973, and after a brief stint in private practice in Russellville and Mobile and a short deployment in the Army Reserve, he became an assistant U.S. attorney (AUSA) for the Southern District of Alabama in 1975. Six years later, President Reagan appointed him the head U.S. attorney for the district.

The Office of the United States Attorneys serves as the principal litigation arm of the attorney general and the Department of Justice. Currently, there are 93 U.S. attorneys stationed throughout the country. Together, they conduct most of the trial work, both civil and criminal, in which the U.S. is a party. They are appointed by the president and must be confirmed by the Senate. On the job, they are vested with tremendous discretion regarding the kind of lawsuits to initiate, and the kind of defenses to raise when the government is sued.

It didn’t take long for Sessions to show his colors once he was installed to run the southern Alabama district.

Early in his tenure, he was confronted with a gruesome case involving two Ku Klux Klan members who in 1981 had kidnapped and murdered a black teenager named Michael Donald. Although Sessions has long taken credit for bringing civil rights charges against the Klansmen, the charges, in fact, were filed only at the urging of Thomas Figures, an African-American AUSA who later became one of Sessions’ most outspoken critics. Figures subsequently collaborated with lawyers from the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division to win a federal conviction against one of the perpetrators.

Sessions, however, turned over the murder prosecution of the lead defendant, Henry Hays, to the local district attorney. Hays was thereafter convicted in state court, and was sentenced to death. He was executed in 1997.

Stories currently circulated by right-wing media asserting that Sessions and his office handled Hays’ murder trial are false. Nor did Sessions play a direct role, as some on the right have written, in securing a $7 million verdict in 1987 against the Alabama-based United Klans of America for Donald’s killing. That judgment was obtained by Morris Dees of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

In a case from 1985, Sessions let his racism completely out of the bag, prosecuting three civil rights organizers, including a former aide to Martin Luther King Jr., for voter fraud arising from a registration drive aimed at poor and elderly residents in several “black belt” Alabama counties during the 1984 Democratic primary election. Sessions based his case on 14 absentee ballots returned by African-Americans that he alleged had been altered. A total of 1.7 million votes were cast statewide—and none was deemed tainted by Sessions.

From the start, the case raised outcries of selective prosecution. The defendants, who hailed from the small town of Marion, northeast of Selma, came to be known as the “Marion Three.” They were acquitted on all counts after the jury deliberated for a mere three hours. Sessions has never apologized for bringing the case and has denied ever since that it was designed to target black voters.

Despite Sessions’ evident prejudice, Reagan nominated him to become a federal district court judge in 1986. His confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee that year were marked by detailed accusations of racism.

Attorney Figures, who went on to become a municipal judge in Alabama and who died last year, testified at the hearings that Sessions repeatedly referred to him as “boy” during their time together at the U.S. attorney’s office. Figures added that Sessions often had spoken of the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Operation Push and the National Council of Churches as “un-American organizations with anti-traditional American values.”

Figures also explained that Sessions initially pressed him to drop the Klan investigation, and maintained that while he and Sessions were involved in the case, Sessions joked that he used to think the KKK was “okay until [he] found out that they smoked pot.”

After becoming a criminal defense attorney in private practice, Figures was indicted in 1992, Sessions’ last year as a U.S. Attorney, on charges of bribery and witness tampering. He was acquitted in a trial held a year later that his supporters claim was brought in retaliation for his criticism of Sessions.Another witness before the Judiciary Committee, J. Gerald Hebert, then a senior trial lawyer with the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division who periodically conferred with Sessions about voting rights cases, testified that Sessions had referred to the NAACP and the ACLU as “communist-inspired” and had faulted the groups “for “forc[ing] civil rights down the throats of people who were trying to put problems behind them.”

Hebert recently told Huffington Post senior justice reporter Ryan J. Reilly that he was “stunned” by Trump’s nomination of Sessions to become attorney general. In retrospect, Hebert said, Sessions “demonstrated gross insensitivity to black people. So Tom Figures reporting that he had been called ‘boy’ by Jeff Sessions, that wouldn’t surprise me at all.”

In his defense before the Judiciary Committee, Sessions adamantly denied ever calling Figures or anyone else in his office a “boy.” He didn’t deny pinning the “un-American” tag on the National Council of Churches or the NAACP, however, but insisted he “meant no harm by it.” Rather, he testified, he intended such remarks only to apply to civil rights organizations “when they leave the basic discriminatory questions and start getting into matters such as foreign policy and things of that nature and other political issues.”

Despite having the full-throated backing of the Reagan administration and vigorous support on the judiciary panel from his close friend, Alabama Republican Jeremiah Denton, who recommended his appointment to the bench, Sessions’ nomination failed to make it out of committee. It was withdrawn the following July.

Unfortunately, Sessions’ legal and political career survived his rebuke by the Judiciary Committee. Rather than fade away in ignominy, he went on to win election as Alabama attorney general in 1994, in which capacity he fought court-ordered desegregation, and he was elected to the Senate in 1996. Today, ironically, he is a member of the Judiciary Committee.

Since taking his seat in the upper chamber, Sessions has amassed a virtually unbroken record of ultra-conservatism, bordering at times on what can accurately be described as authoritarian white nationalism. Among the multitude of views he’s espoused, he has defended voter ID laws and called the Voting Rights Act “a piece of intrusive legislation,” denounced the Black Lives Matter Movement as “radical” and guilty of promoting “false” claims about police abuse, consistently opposed criminal justice reform, and resisted calls for removal of the Confederate flag from government facilities.

He has also supported Trump’s proposed ban on the immigration of Muslims and the president-elect’s vow to build a border wall. He has called for slowing down the rate of legal immigration, cancelling federal funds to sanctuary cities and ending the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship. He’s decried the advent of gay marriage, and opposed abortion rights and the Violence Against Women Act. He’s also been a militant war hawk in foreign policy matters, and a staunch proponent of gun rights and enhanced government spying under the Patriot Act.

As attorney general, Sessions would manage the entire Department of Justice. He would supervise the operations not only of the U.S. attorney’s offices across the country and the Civil Rights Division, but also the solicitor general, who represents the interests of the federal government in cases argued before the Supreme Court. He would have the president’s ear in making recommendations for future Supreme Court nominations.

In short, once installed, Sessions would be ideally positioned to help transform Trump’s central campaign slogan—”Make America Great Again”—into its actual intended objective of making the nation “white” again.

Although Democrats hold only 48 Senate seats following their debacle at the polls, there is still a margin of hope that civil rights and liberties activists can force them to muster up the courage and shame a handful of Republicans to join them in blocking Sessions. Nothing on the near-term progressive agenda is more important than stopping Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III from becoming attorney general of the United States.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.