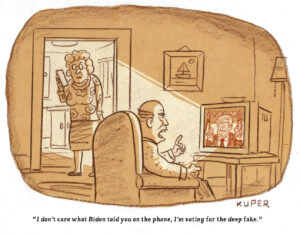

Will Facebook’s System to Detect Fake News Lead to Censorship?

There’s a difference between muckraking and fake news. Determining the difference is too difficult for a computer, even one with the smartest kind of artificial intelligence.

Facebook’s application for Patent 0350675 is either a smart method to use artificial intelligence to root out fake news or a potentially dangerous way of imposing censorship on muckraking media and political satire.

The threat of censorship is especially worrisome now that the search for fake news is becoming automated, with computers guided by artificial intelligence aiding human censors.

Facebook is a leader. It has applied for a patent for a computer device that would have the capability of sweeping through Facebook posts, searching for keywords, sentences, paragraphs or even the way a story is framed. The computer would spot content that “includes objectionable material.” This vague phrase seems to leave the door open for Facebook to censor opinion or unconventional posts that are out of the mainstream, although the company denies it has that intent.

I heard about such automated searching last year when I was working on a story for Truthdig about an organization called PropOrNot. It had compiled a blacklist of more than 200 news outlets that it said were running pro-Kremlin propaganda, and Truthdig was on the list. In the course of finding out how PropOrNot compiled the list and how Truthdig was added to it, I interviewed a well-known communications scholar, professor Jonathan Albright of Elon University in North Carolina.

Albright told me the information was collected basically through an algorithm, or set of instructions to a computer for sweeping or scraping websites or other material on the internet—similar to what intelligence agents do in examining emails.

The computer would be instructed to tag words, sentences, paragraphs or even how the story is framed. I theorized that was how PropOrNot works, scraping sites in search of material that would fit its description of purveyors of Russian propaganda. Apparently, Truthdig and some other publications were incorrectly caught up in a PropOrNot sweep. PropOrNot, which operates in anonymity, told me my description of its methodology was generally correct.

In the course of our conversation, professor Albright told me Facebook was “trying to develop a patent for a fake-news detection system.”

His fear is that “it is turning into a form of censorship or could be developed as censorship.” He said he was concerned that Facebook, Google or the government could develop filters “to determine what is [supposedly] fake and make decisions about that.” They could hunt for particular words, sentences and ways the news is framed. Dissent could be filtered out, as could articles with unusual, non-mainstream slants. “There are going to be keywords and language that will not be standard, and alternative voices will be buried,” Albright said.

That concerned me. I don’t, of course, like fake news of the kind that proliferated during the last election and afterward. Facebook, with its millions of users, is a target for people posting false news. Aware of that, Facebook has partnered with well-known news and fact-checking organizations to root out such “news.” They are ABC, FactCheck.org, The Associated Press, Snopes and PolitiFact.

I wanted to know how Facebook and these organizations determine what exactly constituted fake news. Thinking of how PropOrNot wrongly portrayed Truthdig and other news media as purveyors of Kremlin propaganda, I feared that Facebook and its news collaborators could end up wrongly censoring posts, particularly those of opinion-oriented publications and websites like ours.

I found the Facebook patent application (a Facebook representative told me the company often applies for patents and that shouldn’t be taken as an indicator of future plans). I also discovered an article last November by Casey Newton on The Verge website explaining the application, which was most helpful to me, a non-technical person.

The application envisions using artificial intelligence to scan material that is scored by the computer and given a value. Based on that, “it can be determined whether … the content items include objectionable material.”

Determining what passes Facebook tests are the social network’s community standards. The standards, in brief, ban some nudity, hate speech, images glorifying sadism or violence, bullying and promotion of suicide, terrorism and organized crime. Violation of these standards could mean removal of a post from the Facebook site or its relegation to the bottom of the newsfeed, severely limiting readership.

I asked Facebook how this worked. A representative said that once a post is flagged, either by a person or the computer, it is turned over to teams of multilingual employees who are trained in maintaining community standards.

What about opinions that many consider outrageous or wrong? In December 2015, I wrote a column comparing Donald Trump with Hitler, and people told me I was wrong or at least way off the mark. Would comparing Trump to such an evil mass murderer constitute hate speech and be a violation of the standards? The Facebook representative said the company was not seeking to censor opinion or limit freedom of expression.

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s founder and CEO, has acknowledged that dealing with an opinion piece requires caution. In a Facebook post, he wrote that many stories “express an opinion that many will disagree with and flag as incorrect even when factual. I am confident we can find ways for our community to tell us what content is most meaningful, but I believe we must be extremely cautious about becoming arbiters of truth ourselves.”

Others are not sure how this would work out. I asked USC professor Mike Ananny, another respected internet communications scholar, if Facebook’s automated data search, combined with its community standards, could be used to censor Truthdig or similar opinion journals.

“It’s a good question,” he replied in an email. “I don’t believe Facebook would intentionally try to bury opinion sites like Truthdig, but ultimately, we have to take them at their word because we don’t have the access required to interrogate and audit their systems. Even if it has intentions that we think align with our editorial values, we just don’t know how these intentions play out when they are translated into opaque algorithmic systems.”

Kalev Leetaru, a senior fellow at the George Washington University Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, wrote in Forbes last December, “Remarkably, there has been no mention of how Facebook will arbitrate cases where journalists object to one of their articles being labeled as ‘fake news’ and no documented appeals process for how to overturn such rulings. Indeed, this is in keeping with Facebook’s opaque black box approach to editorial control on its platform. … We simply have no insight into the level and intensity of research that went into a particular label, the identities of the fact checkers and the source material they used to confirm or deny an article – the result is the same form of ‘trust us, we know best’ that the Chinese government uses in its censorship efforts.”

Leetaru’s mention of China brings to mind a new law that initiates an American government effort to identify and counter what officials consider propaganda from foreign nations.

In December, President Barack Obama signed legislation authored by Republican Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio and Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut that greatly increases the federal government’s power to find and counter what officials consider government propaganda from Russia, China and other nations and provides a two-year, $160 million appropriation. It would create a web of government fake-news hunters.

Portman’s office said “the legislation establishes a fund to help train local journalists and provide grants and contracts to NGOs, civil society organizations, think tanks, private sector companies, media organizations, and other experts outside the U.S. government with experience in identifying and analyzing the latest trends in foreign government disinformation techniques.”

It’s bad enough that Facebook and its media colleagues will be scrubbing and scraping for fake news, deciding whether investigative or opinion articles fit into that category. Creating a government fake-news search complex—especially with this Trump administration—is much worse.

Journalism’s job is to cover government deeds and to shed light on actions that reporters, editors, publishers and the public consider wrong. It is journalism’s obligation to investigate and explain government on behalf of the public.

This is “muckraking,” the word I used at the beginning of this column.

Merriam-Webster says the word dates back to the 17th century and means to “search out and publicly expose real or apparent misconduct of a prominent individual or business.” The Cambridge Dictionary says muckraking is “trying to find out unpleasant information about people or organizations in order to make it public.”

President Theodore Roosevelt used the term as an insult to reporters. They, being contrarians, wore the term as a badge of honor, as they still do.

There’s a difference between muckraking and fake news. Determining the difference is too difficult for a computer, even one with the smartest kind of artificial intelligence.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.