Why the Real Labor Day Is May 1

Whereas May Day "celebrates the historic power of the working class to oppose its oppression and fundamentally alter society … Labor Day is just another legacy of worker defeat," writes Jonah Walters in Jacobin magazine. Janitorial workers picket in front of the MTV building in Santa Monica, Calif., in 2008, threatening to strike. (Staeiou / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Janitorial workers picket in front of the MTV building in Santa Monica, Calif., in 2008, threatening to strike. (Staeiou / CC BY-SA 3.0)

As a Jacobin article reminds us, “American workers did contribute at least one lasting legacy to the international movement for working-class liberation – a workers’ holiday, celebrating the ideal of international solidarity, and eagerly anticipating the day when workers might rise together to take control of their own lives and provide for their own well-being.” But “that holiday is May Day,” writes Jonah Walters. “Not Labor Day.”

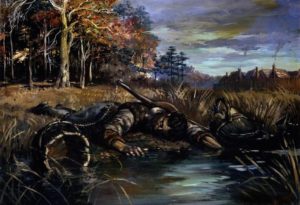

Tracing Labor Day’s conservative roots, we’re reminded that the holiday was established in 1894, by President Grover Cleveland “as a way to de-escalate class tension following the Pullman Strike, during which as many as ninety workers were gunned down by thousands of US Marshals serving at the pleasure of railway tycoon George Pullman, one of the time’s most hated industrial barons.”

Walters explains:

In an impressive display of working-class solidarity, more than 150,000 railroad workers in 27 states joined the strike in the weeks that followed, refusing to switch, signal, or service trains pulling Pullman cars. Suddenly, with all trains at a standstill, the railway system was under the control of the American Railroad Union, then led by Eugene V. Debs.

President Cleveland conveniently invoked the executive responsibility to deliver mail to claim the strike was illegal and unjustified because the US Postal Service relied on train travel. He mustered a heavily armed force of more than 14,000 US Marshals, soldiers, and mercenaries to break the strike. After days of fighting and more than 30 workers killed, the strikers were dispersed and trains began to move.

The Pullman Strike was one of the most catalyzing moments in American history, leading working people all over the country to draw revolutionary conclusions — including Debs, who read Marx for the first time while imprisoned for his role in organizing the strike.

Cleveland was wary of the response to his actions. He signed Labor Day into law a mere six days after busting the strike.

Convincing American workers to accept such a transparently disingenuous maneuver was a hard sell. But Cleveland found an effective ally in Samuel Gompers, the president of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), a conservative coalition of skilled workers that had opposed the strike.

Gompers immediately endorsed the president’s holiday — Cleveland even presented him with the pen used to sign the holiday in law. Gompers later wrote a superlative column in the New York Times praising Labor Day as the harbinger of “a new epoch in the annals of human history.” He made the absurd claim that Labor Day “differs essentially from some of the other holidays of the year in that it glorifies no armed conflicts or battles of man’s prowess over man,” and wrote scathingly about the “dark side of the labor movement” represented by the Pullman strikers.

Although previous Septembers had seen small workers celebrations in many states observing the end of summer, the first federally protected Labor Day was marked in 1894 with an AFL-supported parade.

Debs still sat in jail with seventy-one others arrested during the Pullman action. Around the same time, the American Railway Union — previously the most powerful union in the country — was forcibly disbanded after the AFL denied its appeal.

Labor Day marks our historic defeat, not our triumph.

May Day celebrates the historic power of the working class to oppose its oppression and fundamentally alter society. Though it’s a welcome break from work for many of us, Labor Day is just another legacy of worker defeat.

Read the rest here.

–Posted by Roisin Davis

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.