Why Did a Man Starve to Death in an Arkansas Jail?

Because of multiple broken systems. Larry Eugene Price as he appeared in life. Photo supplied by the Price family.

Larry Eugene Price as he appeared in life. Photo supplied by the Price family.

Larry Eugene Price told social workers that he’d seen a snake crawling on the ground. Price, 51, then said a man had stabbed lit cigarettes in his eyes. It was February 2020, and the staff at the Crisis Stabilization Unit in Fort Smith, Arkansas made a note in his case file that he’d suffered from hallucinations and paranoia after being diagnosed with schizophrenia at the age of 22.

The unit is designed to work with police to place mentally ill people in treatment instead of jail. But six months later, on Aug. 19, when Price shouted at police officers and flipped them off, he was arrested and charged with “terrorist threatening in the first degree.” Instead of being placed in treatment, he would spend more than a year in the Sebastian County Detention Center pre-trial.

On Aug. 29, 2021, guards found Price unresponsive in his solitary confinement cell. His eyes were wide open. In the previous two months, he hadn’t eaten his meals, but had rather chewed on the styrofoam trays. It was not uncommon for Price to scream and throw his feces at the walls of his segregated cell. His bed was soaked in urine when guards found him. The cell had flooded.

This picture was taken when the brothers went to their

father’s funeral in 2008. Larry then weighed 185 pounds.

Photo provided by the Price family.

The United Nations secretary general classifies more than 15 days in solitary confinement as torture. Even mentally stable people who get put in solitary experience paranoia, panic attacks and hallucinations. In the 19th century, on a tour of America, Charles Dickens — not known for an overly rosy view of humanity — was shocked when he witnessed prisoners in solitary. “He is a man buried alive,” Dickens wrote.

Emergency Medical Services clocked Price’s weight at 90 pounds on a 6 foot 2 inch frame at the time of his death. In autopsy photos, he looks like the victim of a famine. His feet are bloated and wrinkled from the time he’d spent immersed in rank water. There is a bed sore on his bone-thin thigh.

“My brother did not have to suffer and die,” Rodney Price, Price’s younger brother tells Truthdig.

Price’s death encapsulates nearly everything wrong with the U.S. criminal justice system, and the conditions that make it one of the deadliest in the world.

Price was arrested, instead of treated, during a mental health crisis. He remained in jail because he didn’t have $1,000 for bail money or $100 bond. In solitary, he was neglected by guards. Between Aug. 1 and Aug. 29, they made up to 4,000 wellness checks on him, each time, writing “Inmate and Cell OK.”

Like in many parts of the rural United States, the jail is the biggest employer in Sebastian County. Like many corrections officers, the guards at the Sebastian County Detention Center are underpaid, with a salary of only $34,000 a year.

Price’s deterioration was noted, and largely ignored, by staff with the Oklahoma-based private health company, Turn Key Health, charged with keeping jail inmates healthy. The company costs Arkansas taxpayers $59,056.50 per month. Price’s Turn Key intake questionnaire notes “Mental Illness or Nervous Problems?” “Yes.” “Did not want to get up. Decline in health,” Turn Key staffers wrote on his daily observation reports through October 2020. “Refused to comply,” which put him at risk of “Illness or even death,” they wrote in November, nine months before his death.

“It’s difficult to describe how atrocious this is,” Erik Heipt, a Seattle-based attorney representing Price’s family, tells Truthdig. “A developmentally disabled, mentally ill man, who couldn’t afford his low bail amount, was held in solitary confinement for a year. Think about that.”

Heipt notes that Price should never have ended up behind bars. It was a failure of the system. And the system continued to fail him until he died.

“They had a duty to provide him with adequate medical and mental health care,” Heipt adds. “They flagrantly violated that duty. They allowed him to waste away — to slowly die of starvation and dehydration. There is no excuse for this. None.”

What should have been a brief mental health hold turned into a death sentence.

“They allowed him to waste away and to die,” Rodney Price says.

* * *

Hell on the Border

Fort Smith sits at the border with Oklahoma. It was founded as a military outpost in 1817 to quell conflict between the Osage and the Cherokee tribes displaced from other parts of the South by white settlers. Twenty years later, it would be the final destination for the Five Tribes on the Trail of Tears. Sixty thousand people were forced into “Indian Territory,” with close to 10,000 dying of starvation and disease along the way.

Criminals of all stripes, from thieves to murderers, descended on so-called “Indian Territory” to take advantage of the vulnerable population and lack of federal judicial authority. In 1875, Isaac C. Parker was appointed to the bench of the U.S. Court for the Western District of Arkansas. His task was to wrangle the frontier into order by using warrants to go after whites who were wreaking havoc there. A jail was built in the basement of the courthouse.

In 1885, Anna Dawes, a journalist from Massachusetts, toured the jail. She described the facility as “horrible with all horrors … hell upon earth,” in an article she published the following year. She called it a “piece of medieval barbarity” and asked, “What excuse has the government of the United States…for the existence and continuance of this scandal?” The jail came to be known as Hell on the Border.

Up to 50 men each were crowded into two cells, with one bucket for washing. The men would throw the water on the ground to freshen the air. On hot days, it turned to malodorous steam. To pass the time, the men tried to exercise by running back and forth in the small space.

Guards threw sawdust on the ceiling to mask the stench of unwashed men and shit from reaching the courtroom above. The only windows, with heavy bars, barely let in light. Men arrested for theft were housed in the same small space as killers headed for the gallows, which stood across from the courtroom. In the 21 years he presided over the Western District of Arkansas, starting in 1875, Judge Parker sentenced 160 men to death. He became known as “the Hanging Judge.”

Today the courthouse, the jail and the gallows are historic sites. The National Park Service invites history buffs to Fort Smith to experience the Wild West. “Explore life on the edge of frontier and Indian Territory through the stories of soldiers, the Trail of Tears, scandals, outlaws and lawmen who pursued them.”

You can visit the musty jail. The park service has recreated how the men slept — on thin mats with barely any cover. The wooden ceiling is low and claustrophobic. The gallows are freshly painted white. “Please keep off the gallows,” a sign reads. “Respect it as an instrument of justice.”

Later that day I went to the Sebastian County Jail, a mere half mile away, where I talked to about a dozen men over the messaging system about the conditions there. They described the facility as overcrowded, filthy and dangerous.

Judge Parker — who, ironically, thought the death penalty should be abolished — had been following the law to try to stop murderers and rapists from abusing Native Americans. But in our more enlightened times, a man could go to jail for a year for giving the bird to cops during a psychotic episode, and then die a horrible death there.

* * *

Sebastian County Detention Center

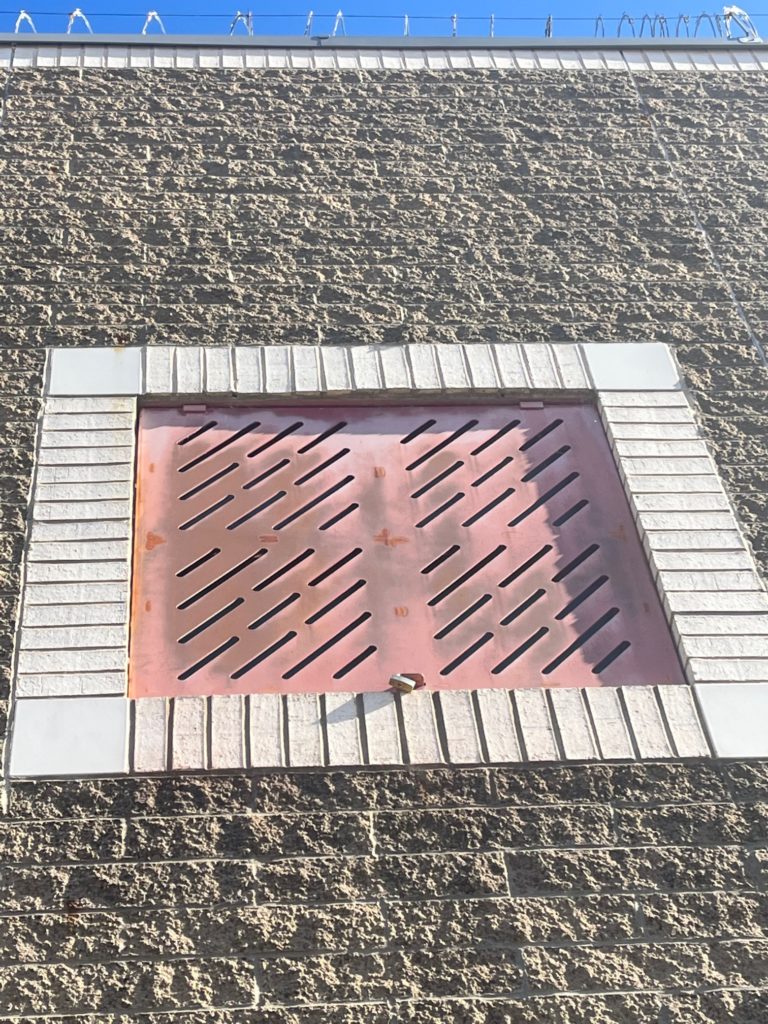

According to multiple inmates I spoke with, eight men share a small cell designed to house two to four. Sometimes 15 men are put in a cell for six. The men report violence, medical neglect, unsanitary conditions, inedible food and the occasional rat shit on the breakfast tray. From the outside, the windows, painted red, have miniscule diagonal slits — they literally let in less light than the windows that so appalled Anna Dawes.

“It’s either hot as hell or cold as hell,” an inmate, who wishes to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, tells me over the jail’s messaging service. The men sleep on thin mats — oddly similar to the sleeping arrangements of prisoners in the mid-19th century. In another eerie parallel, the jail allegedly mixes people detained for low-level crimes with more hardened criminals.

“We are forced to live with both felons and misdemeanors, together,” another man adds. “They shake us down.”

“Every day is different here. Sometimes I’m awoken to someone being beaten by officers here…sometimes officers will jump on an inmate for talking crazy to them,” another man tells me. “They will call us a bitch, then place us in a cell with other people that they know we are into it with so we can get jumped.”

“There is a guard that tells, ‘Kill yourself’ to the inmates,” one man told me. He recalls how the guards just stood around when one of his cellmates suffered a seizure. “They thought he was just faking, but he wasn’t.”

Another man wants me to know that the guards aren’t all bad.“Their (sic) are some good officers here too that gets a bad look because of other officers.”

“We are forced to clean … which is a job without pay. We have to clean blood, piss, shit and so on,” another inmate said.

“No PPE for cleaning feces or blood,” says another. “People with COVID forced to share cells and be in general population.”

Both the desk clerk and bartender at my hotel have been inside the jail. “They treat you like a dog,” the desk clerk tells me. “It’s unclean. It’s so unclean.” She repeats that it’s unclean at least five times. She spent just 24 hours there, for driving without a license. She says she spent a month “not eating” to pay a lawyer $1,000 to clear her (nonviolent) priors so she never goes back. The bartender says that it’s scary when they put people with misdemeanors in the same cells as people accused of serious felonies. One man begged me to call his mother for help.

Price’s death doesn’t appear to have spurred a reckoning. Mentally ill people are still being arrested, instead of helped, and placed in solitary.

“Mr. Terrell Horne is a mentally ill, old man of color,” an inmate who wishes to remain anonymous tells Truthdig. “They put him in seg.”

Horne’s jail records show his “prisoner type” is “Mental Incompetency.” They also confirm that the 61-year-old, arrested for burglary, is in solitary. He’s been behind bars since July on $5,000 bail.

Two inmates asked guards if they could look in on him. Two days later, the guards agreed and what they saw horrified the men.

“He was forced to stay in feces, with a clogged toilet with cigarette butts in the toilet,” the inmate says. “The other guards called Mr. Horne an animal, whistled at him and kicked him.”

Virtually everyone in the jail is being detained pretrial because they can’t afford bail.

“We live in awful conditions,” another man behind bars tells me. “We are still human.”

“No Jackets”

Visitors to the jail sit in a cramped, blue room and dial into a video monitor, and there are RULES. No tank tops. No sleeveless tops. “So absolutely no summer tops at all.”

“NO SHORTS!” another sign reads.

No overalls, for some reason. “The best way to be sure your visit takes place is to dress as if you are meeting someone’s grandmother for the first time.” “No jackets of any kind that open in the front.” “Absolutely NO jackets” another sign confusingly says.

If you’re the kind of person who likes to wear a jacket but you don’t have the funds to make bail for your loved one, you can trot across the busy road and the train tracks to “Bail Bond Exit Company.” “Don’t leave jail without us” their business card jauntily declares. The card shows four men in cowboy hats hoisting rifles. The company is part bail, part pawn shop. In the past, people have traded in belongings to make bond (they’ve ended the practice but won’t say why), and the office is disconcertingly overstuffed with old arcade games, dead, stuffed deer, guitars and old saws. The company charges customers 10% of the bail amount. The fee is non-refundable.

The Pressure, the Tension

How to Help- ACLU of Arkansas – The ACLU of Arkansas (ACLU-AR) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that uses legal, legislative and public education methods to protect and promote a broad range of constitutional issues including, free speech, racial justice, privacy, religious liberty, reproductive rights, LGBT rights, and more.

- The Bail Project – The Bail Project is a national nonprofit organization that pays bail for people in need, reuniting families and restoring the presumption of innocence.

- Silenced: Voices from Solitary – The digital project Silenced: Voices from Solitary in Michigan, launched by Zealous in 2021, is part of a larger campaign to end the use of solitary confinement in the state.

- Unlock the Box Campaign – Unlock the Box is a national advocacy campaign aimed at ending solitary confinement in all U.S. prisons, jails, detention facilities, and juvenile facilities, and bringing the United States into full compliance with the UN’s Mandela Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners within 10 years.

- Become a penpal with an incarcerated person – It’s easier than you think. Sign up for an account with JailATM. Look up the name of the Sebastian County inmate. JailATM will ask for the state, the facility and last name of the inmate. Federal prisoners can communicate through Corrlinks.com, and state facilities mostly use JPay.

“Being sheriff would be the best job in the world,” Sheriff Hobe Runion tells me in his office. “If it weren’t for the jail.”

Runion is voluble and likes to tell jokes. He disputes that the jail is unsafe, but admits it’s extremely overcrowded. There are currently 400 inmates. Capt. William Dumas, who runs the jail, tells me the facility operates at its best with 330 detainees. “When you’ve got so many men … the pressure, the tension, it builds,” Runion says.

The Arkansas state prison system is designed to hold 15,431 people. The state prison population exceeds 17,000. So state prisons send inmates to county jails, which were not designed to hold state prisoners for months as their trial dates drag on and on. Runion recalls another sheriff, years back, became so frustrated he put the jail’s state prisoners on a bus, drove them to the Arkansas Department of Corrections and handcuffed them to the building.

“After 30 years in law enforcement, I can’t believe that my goal now is to have fewer people in jail,” he says. His commitment to decarceration is limited, however. Runion doesn’t exercise his authority to let out people charged with misdemeanors, which he clocks at 30. “Just because their current charge is a misdemeanor, it doesn’t mean that they don’t have more serious charges.”

Many of his wards suffer from what he calls the social problem trifecta: Mental illness, addiction and homelessness. Runion and Dumas seem none too happy that the jail has to operate as part mental institution, part homeless shelter, part rehab. The guards aren’t trained to handle those tasks. And the low pay doesn’t help. “You can make more money working at the chicken plant at Van Buren,” Runion says. He notes that Arkansas ranks 49th in the country in correction officer pay (“Thank God for Mississippi!” he quips).

“Mental health care in Arkansas is medieval,” Runion says. He says men wait for months in jail for a hospital bed to open up. Dumas adds that it’s the very people they categorize as “mentally incompetent” who end up getting locked in solitary because they cause disturbances. “Being segregated is part of any corrections, anywhere in America,” Dumas says somewhat defensively when I point out that the U.N. considers long-term solitary confinement to be torture. “We don’t put anyone there and forget about them. How they act dictates what they get. And they’ve got a set of rules and a handbook very clear of what they can do.”

Dumas clearly takes pride in his work. He tries to train the guards to be fair-minded and professional. “Be fair, be consistent, nothing’s personal, no matter what happens, we keep our professionalism,” he says. “It’s really hard … we’re dealing with these people on their worst days. They lose their loved ones … moms, dads, kids even, while behind bars. So now we become the compassionate ones and we’ve got to help keep this person in the right frame of mind.”

He’s especially proud of PACT, a peer-led substance abuse program. Spearheaded by a young, bubbly woman named Tricia Watson, herself a former addict and inmate at the facility, the program helped 81% of the female participants stay out of jail the first two years. It was so successful that they got more money to start a similar program for the men, led by another former addict.

“We really hang our hats on that program,” Dumas says. Watson confirms that Dumas and the sheriff have her back. “I tried to start a program like this in other counties but they weren’t interested,” she says.

Dumas takes me on a tour through parts of the jail. The first stop after intake drives home the point the mental health problems are pervasive.

“Those are suicide cells,” Dumas says, pointing to three locked iron doors. If someone comes in and appears suicidal, they’re put in a straight-jacket and placed in the small, padded cell.

As we walk down the hallway, gaunt men in orange jumpsuits trudge around the hallways, some in leg shackles. They’re the inmates who are granted more freedom and go around cleaning and doing various other jobs. We pass the women’s cell, the window covered in cardboard so men can’t stare in. A medical unit. Dumas gestures at it with pride, but it’s just a small, cramped unit with three rusty metal cots. There’s the laundry room, where thin mats lay tangled on the ground. “Do they sleep on those? I ask. “How come?”

“So when they tear them up it costs less to replace them,” he says with a curt laugh. He takes me to the infirmary. “They can get all the health care in here.” There is, indeed, an eye test chart. But I notice a poster with prices for access to medical care. It costs $20 to get a consultation with a nurse and $30 to possibly see a doctor. We pass a segregation cell. It’s solid metal with only a food tray slot at the bottom. You wonder if there’s anyone in there panicking, hallucinating or throwing their feces at the walls.

“Before He Got Like That”

I asked the men I spoke with if they knew Price. They checked in with each other, but no one remembers him. His brother wants people to know him as more than the husk of a corpse in those autopsy photos.

“My brother really cared about his family,” Rodney Price says. “He loved his family. He had a good sense of humor and enjoyed making other family members laugh. He was a loving, caring person.”

He’d mimic their uncles and aunts. “His impersonations of them were spot on and very funny.” He loved to breakdance and beatbox. “This was fun and exciting to watch.”

His aunt, Beverly Redford, says he told her she was his favorite aunt. “Growing up he had no problems. He went to school and everything. I know the family loved him. I know he was crazy about me!”

Around the time he turned 17, he started showing signs of illness.

“He was messing up. Getting into trouble. He started walking down the street talking to himself.” says Redford. “He had a good personality. It was real good. Before he got like that.”

Rodney says his brother, who was two years older than him, had never been violent.

“He wasn’t capable of committing a crime,” he says. His aunt agrees that he didn’t have a violent bone in his body.

Before he got sick, Rodney recalls, his older brother had some developmental challenges, but was a fun-loving kid. “He couldn’t comprehend things as well as others. But he enjoyed life,” Rodney says. “He ran track for special needs athletes. He was a sprinter. He loved basketball. He loved biking. He loved fishing. We went fishing a lot. I’m sure he still enjoyed those activities in his adulthood. But his mental health issues became severe over time and took over his life.”

In his assessment by the Crisis Stabilization Unit, they list “sense of humor” as his main strength. In it, he says he believes in Jesus but stopped going to church after his ex-wife cheated on him. His mother left when he was 14. He thought that she’d never wanted him. He stayed with his dad, who was a heavy drinker.

A Way Out- Abolish cash bail.

- Ensure people’s mental health issues are treated and they have access to medication.

- Abolish solitary confinement.

- Stop prosecuting people for misdemeanors (with the exception of domestic violence incidents because those risk escalating into fatalities) in order to lower jail populations and overcrowding.

- Better training and higher pay for guards.

- Accountability for abusive or negligent guards.

- More accountability for private contractors, especially health companies.

He told them that he’d like to get therapy and medication management, but it was tough since he was homeless. He’d been sleeping in his car near the police station. Nevertheless, they noted that he was “well groomed.” His aunt says that he’d trudge miles to get his medication — he was committed to managing his illness.

“I think people are after me all of the time and that scares me,” he told the staff at the Guidance Center, a community health group. “I just need my shot,” he said. To “quiet the voices in my head.” Redford believes the jail withheld his medication. Turn Key records show that when he was being “disruptive” they didn’t give him the meds.

Redford points out that he’d still be alive if he’d had $100 for bond. “I didn’t know he was in trouble! $100 to get out. What is $100? I’d have paid it in a heartbeat. I had no idea he needed that. They never told me.”

Redford was woken by police at 4 a.m. “Do you know a Larry Eugene Price?” they asked. They put a bundle of clothes on her porch, the last thing he wore before his arrest.

“I asked, ‘How did he die?’ ” she says. “They had no answer for that.”

Eventually, she was able to suss out the details. “He passed 15 minutes after they found him,” she says. “My baby taking his last breath…”

Price worked as a California corrections officer for decades. He can’t fathom what the guards were doing as his brother got more and more visibly ill.

“Corrections officers are supposed to be doing well-being checks every 15 minutes,” Price says. “They obviously weren’t doing their job. There is no excuse for what happened. He should’ve been receiving medical and mental health care the whole time,” he says.

“They should have been carefully monitoring his food and fluid intake and output. At some point, it became obvious that he belonged in a hospital,” he says. “As a former corrections officer, and as a human being, I would’ve called 911 when I saw his skeletal appearance. I can’t understand why no one did that.”

This article was made possible in part by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

This is so infuriating! There is no excuse for for-profit prisons. Period! They bleed taxpayers dry! They traumatize both sane and insane alike. Save us from the worship of the almighty $$$$$

this so