Who Is Ayn Rand?

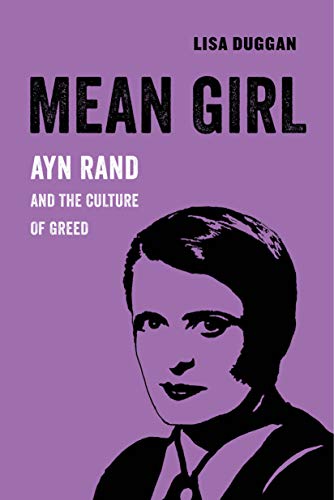

A new book argues weakly for the influence of Ayn Rand on our culture—after all, the dominant classes in America were greedy and selfish from the get-go. Novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand. (Julius Jääskeläinen / Flickr)(CC BY 2.0)

Novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand. (Julius Jääskeläinen / Flickr)(CC BY 2.0)

“Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed”

A book by Lisa Duggan

In the preface of her new book, “Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed,” New York University professor Lisa Duggan writes that her cultural study of Ayn Rand “is focused on illuminating the ‘how did we get here?’ questions’’ about our current politics, “via analysis and speculation about the role of feeling, fantasy and desire in maintaining political economies.”

Duggan’s clever title suggests a contemporary look at Rand, tracing cultural inroads she paved to the disaster capitalism of these times. (“Mean Girl” refers to the movie—and later Broadway play—“Mean Girls,” about teen girls and their power plays in high school cliques.) Rather, the book is a zoom through political history and Rand biography, in a sort of on-the-one-hand-vs.-the-other way, without delivering cohesive evidence to support the stated inquiry.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Mean Girl” at Google Books.

If “Mean Girl” is an introduction to Rand’s work, it will save readers some time, but Duggan’s cultural analysis is disappointingly thin. For the most part, the book reads like a thesis paper from a survey course, reliant on previous research, ideas, and writing. Thankfully, the author chose not to stretch her study past its 90 pages (plus notes,) in sharp contrast to the voluminous meanderings of her subject.

Early in the third of the book’s seven short sections, Duggan does cover a less-rehashed detail from Rand’s life that provides creepy context to her fiction and philosophy. Rand admired the killer and pedophile William Edward Hickman, and used him as a model for an early fictional character in her first, and unfinished, novel, called “The Little Street.” She drew from his “wonderful sense of living” for her central character Danny Renahan. Mean Girl, indeed. (Rand contended she didn’t admire crimes, only certain exceptional antisocial qualities.)

Duggan says Rand’s core contributions to neoliberal politics are not ideas, and here I agree. However, she calls Rand’s novels—especially “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged”—“conversion machines,” and sees their primary power in eroticized capitalism played out through virile heroes and appreciative heroines in lust. Young people can be forgiven for being enthused by the novels’ steamy melodramatics that elevate pure talent and bold nonconformity. But it’s hard to view sex-as-delivery-system as unusual, even if, for its time, it was less veiled in romantic language. (Predating Rand’s surge in notoriety, “Casablanca” wove cynicism, sex, and romance to captivate its viewers, but settled on sacrifice as key, not only to the victory of goodness, but to the peace a clean conscience affords.)

Characters like Ellsworth Toohey are recognizable weasel types, who wheedle for position and power, and earn the disdain of readers and Rand’s heroes and heroines alike. So too, Rand’s ambivalent disillusionment with Hollywood, after realizing its studios were not led by firebrands, just box office chasers, has long been shared by many, including those who disparage her ideology. Like the future Fox News, Ayn Rand seized on fractional truths and wound them into diatribes, igniting passions while ignoring disconnections to logic or overarching facts. But as with 24/7 news cycles, there’s not much there (or new).

Duggan references economists and philosophers, such as Alan Greenspan, Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, who admired Rand and helped promote her thinking. Those who touted Rand may have been foolish, but they were not stupid; she was useful. As with Mitch McConnell, who blathers about responsible government and fairness, many people can discern the truth from his actions or inactions that he hasn’t the slightest interest in responsibility and fairness, much less democracy.

Scathing critics, like William F. Buckley, are also discussed, and Duggan notes that Rand’s popularity waned at times over the decades. But she supersizes Randian influence in what has come to pass politically and economically. The move to radical capitalism took effect slowly, and Rand was often out of sync with political and economic history. (When “The Fountainhead” was released in 1943, most critics rejected it. Eventually, an audience grew, making it a bestseller.) Post-World War II American culture was full of entertainment vehicles such as popular Western movies that served as propaganda for another kind of individualism: progress-oriented, altruistic, and good-hearted.

Generally, these powerful movies posed a mythic west notable for heroic individuals who assisted society and commerce through community-building—though they stood outside—without resorting to greed, theft, and destruction. Violence came from so-called savages, and heroes only reacted to it, defending the community. Men were macho; women looked longingly at them, fearing for their safety. This romantic exceptionalist myth aligned with Rand’s hatred of communism and Cold War politics, but not the extreme avarice of super-capitalism. (Rand claimed to favor free markets and revile crony capitalism. But ego-drenched individualism of the sort she admired often pairs with the clubs and exceptions made and protected by crony capitalism, which quashes free markets.)

America’s self-perception as reflecting ethical, communal values was still dominant when “Atlas Shrugged” appeared. Duggan writes: “The world of the contemporary United States, the setting of ‘Atlas Shrugged,’ has fallen heavily under the sway of collectivist government regulation. The result is civilizational regression, a slide back to more ‘savage,’ ‘tribal,’ ‘primitive,’ or Asiatic modes of life.” (Footnoted to Rand’s journals, edited by David Harriman.)

That world, and John Galt’s Gulch setting, had little in common with the political, economic life of America of 1957. Significant racial and historic injustice notwithstanding, the white middle class—the demographic that Rand and most entertainment targeted—enjoyed strong economic growth and fruits, and its collapse was not imminent. Randian rants, her characters’ lengthy speeches, were as likely to bore readers as create followers. And while her exclusion of nonwhite populations lined up with a consistent current of American racism, her anti-religious, anti-family attitudes held no sway with most citizens, as evidenced by the church-going, baby-booming times.

It wasn’t until the Vietnam era that antiheroic subversions of pop propaganda sifted noticeably into the culture. As personified in hit movies like “The Graduate,” “Easy Rider,” “M*A*S*H” and others, these antiheroes were more disaffected than driven, more brooding than brilliant.

The right-wing accumulation of power since Reagan was more a reaction to youth rebellion and conservatives’ subsequent lost clout in the ’60s and ’70s than a result of Rand’s cultural heft. Sexual freedom was a major cultural outgrowth of the ’60s. Was this connected to Rand, too? That’s doubtful; more likely, it followed access to birth control and the relative freedom that afforded women.

Rand packaged her greed somewhat palatably, enlisting the language of morality. Despite her atheism and promotion of free sex, connecting capitalism and morality proved irresistible to ideologues, and they propelled her as their salesgirl.

Still, the evolutionary trail for today’s apostles of aggressive acquisition points more solidly to the furtive efforts of the right to increase representation throughout the states, and within every branch of government. It took 30-plus years, and steady power consolidation through media and political contributions for the worst inclinations of Rand’s worldview to become “hot” again, and stick. Growth of inequality paralleled the “successes.” (Rand’s resurgent popularity after the 2008 crash was as contradictory and confounding as many of her arguments. Tea partyers and Peter Thiel types make the most incongruous of comrades.)

Though Duggan places Rand’s work as pivotal to the world today, her never-quite-dead writing didn’t change others so much as provide cover for what was desired all along.

After all, the dominant classes in America were greedy from the get-go, stealing and raping people and land, under the guise of creating a democratic land of liberty. As Christopher Hitchens, all smiles and snark, commented in 1996 at the Manhattan Institute, on Rand’s impact on the American right: “I always thought it quaint and rather touching that there is in America a movement that thinks people are not yet selfish enough. …They think that America is already rotten with too much socialism and compassion. It’s so refreshing that there are people who manage to get through their day actually believing that.”

Rand’s ideas and philosophy were guided more by bitter personal experience and exaggeration than reason and rationality—attributes Rand insisted were of the highest value in life. Lacking both reason and rationality, as well as complexity, there is little to grapple with in her work. Objectivism, an Orwellian label she employed to elevate some of America’s destructive tendencies, upends the word “objective” and renders it meaningless.

Famous followers of Rand, some of them inveterate liars, abuse language daily. The explosion of this technique to subvert reality has come through aimed media, repetition, and dark money, not Ayn Rand. Without power brokers, her feelings, fantasies and desires would have fully faded from view long ago.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.