When Justice Is Skin-Deep

The falsely accused Duke lacrosse players deserve their indignation, but so does Jerry Miller, who spent 24 years in jail for a rape he did not commit. It turns out there are many innocent men -- too many of them African-American -- who have done time they shouldn't have, and there are probably many, many more.WASHINGTON — It is safe to assume that Jerry Miller will not become an international media sensation.

His exoneration for a rape he did not commit does not have the makings of a cultural psychodrama on the order of the Duke University lacrosse team saga. For one thing, Miller is black and working-class, not white and upper-middle class, as were the Duke men who were falsely accused. Miller is — or was, before he spent 24 years in prison as an alleged rapist — a young man who’d left high school at 17 to join the Army. He’d just turned 22 and was working as a cook in 1981 when the police picked him up. He’d never before been arrested.

Miller’s arrest for a brutal sexual assault and kidnapping in a Chicago parking garage was based on one officer’s reaction to a composite sketch. The likeness seemed to resemble a man the cop had questioned days earlier because he supposedly was looking too closely at some parked cars. The rape victim couldn’t initially identify Miller; the garage attendants claimed they could.

“The composite sketch wasn’t me,” Miller told me in an interview from New York, where he’d flown to celebrate his good fortune with his lawyers. “You didn’t even have to have good vision to show that. This composite was of a man without a goatee. I had a four-inch goatee. How could you decide it was me?”

On Monday, when a Cook County judge officially cleared him of all charges, Miller became the 200th person to be exonerated based on the work of the Innocence Project, a New York-based network of lawyers who, through the use of DNA evidence, seek to clear those who have been wrongly convicted.

If the howls of indignation that rose up from the Duke case are to be more than an outpouring of national hypocrisy, then it is to cases such as Miller’s that the country and the media must turn their attention.

The improprieties that collided to ensnare the Duke students — false or inconsistent identification by the victim, prosecutorial misconduct, the withholding of potentially exculpatory evidence from the defense, a racially incendiary atmosphere — are common in wrongful convictions. The difference is that the 200 people exonerated through the work of the Innocence Project served an average of 12 years in prison. Fourteen were on death row at the time they were cleared. Earl Washington, a developmentally disabled man from Virginia who was cleared of rape and murder in 2000, was nine days from his scheduled execution.

“We found that in 50 percent of our cases there was serious police or prosecutorial misconduct — that’s what you had in the Duke case,” says Peter Neufeld, co-founder of the project and one of Miller’s lawyers. “Hopefully more people will now want to try to prevent that kind of prosecutorial arrogance and indifference to truth.”

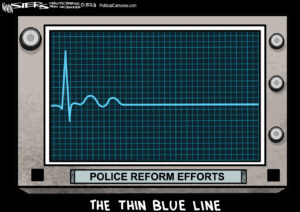

It is the enduring hope — that the country will fix the systemic failings within the criminal justice system. Yet the discussion is largely absent from our tough-on-crime political conversation, because the failings harm African-Americans and other minorities most. For example, though interracial rapes are rare, constituting about 12 percent of reported sexual assaults, 66 percent of blacks who’ve been exonerated through DNA evidence had been wrongly convicted of raping white people, according to the Innocence Project. About half had been misidentified by white rape victims.

Sloppy or slanted identification procedures, interrogations that elicit false confessions, faulty — even fraudulent — presentations of scientific evidence in court all play a role. A 2004 law guarantees federal convicts the right to petition for DNA testing to support a claim of innocence, but the crimes that typically involve such evidence are overwhelmingly state prosecutions. The law encourages states to seek federal funds to improve their evidence handling and post-conviction testing but, according to Neufeld, few have pursued the money. “There are plenty of prosecutors’ offices in the North, South, East and West who say, ‘Once that conviction is affirmed on appeal, that’s it,’ ” he says.

That was not enough for Miller, who began writing to the Innocence Project in 2000 from the penitentiary where he’d spent most of his adult life. This week, he’s been sipping champagne and sightseeing in New York. “I hope that I don’t have to suffer no more,” he says.

The man who committed the rape for which Miller was wrongly convicted was found through the same DNA evidence that cleared Miller, Neufeld says. He is now serving time on other charges.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at symbol)washpost.com.

© 2007, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.