What to Do About American Plutocracy

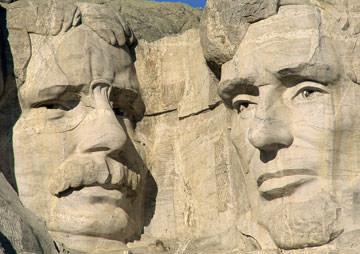

All is not lost. Change has happened in the past, against severe resistance, three times since the Civil War. Teddy Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln on Mt. Rushmore. Shutterstock

Teddy Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln on Mt. Rushmore. Shutterstock

A week ago this column asserted that the present electoral system in the United States now places the U.S government on sale every two years — the presidency and congress every four years, and the entire House of Representatives and a third of the Senate, as well as assorted state governors, judges, and other officials, every two years, as in the mid-term election that took place on November 4.

The argument I made and make is that since national elections now are largely won or lost by the quantity of paid and unregulated television advertisements (or so politicians and professional observers are convinced, a possibly self-fulfilling expectation), those who have the largest amount of money at their disposal win the elections. There are few exceptions.

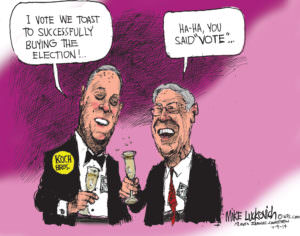

This is not as things should be, but overall it was the result of the November 4 vote. The success of big money was even greater than widely expected. Hence Americans now live in a plutocracy: the country that claims to lead the world is largely controlled by major American corporations and financial groups, and exceedingly rich individuals.

The question posed is can anything be done to reverse this situation, in which money has steadily accumulated national political power until reaching the seemingly decisive position it possesses today. The international economy’s present tendency, as the French economist Thomas Piketty has recently argued, is to augment the fortunes of the already rich, since the rate of return on investment tends to run ahead of the rate of growth in the overall economy.

The rich are not, as mainstream economists (and Republican Party candidates and supporters) have argued for years, “the creators of jobs.” Industry does not, as assumed for many years, support an enlarging workforce. What it does produce is enlarging return for investors.

In the economy of the past three decades, technology has tended to destroy jobs — that, after all, is one of its principal purposes, cost-reduction. The globalized economy has tended to export those fields of manufacture that still require human employees to poor countries, where wages are low and working conditions poor. As governments of countries thus favored by globalization tend to do what they can to maintain conditions that attract foreign investment, industry moves to where conditions are worse and wages lower: thus the competitive race to the bottom.

There are countertendencies, of course. There are enterprises convinced that a well-paid and skilled labor force is an asset. Public opinion tends to oppose the most sinister consequences of globalized manufacturing and services. But there is as yet no convincing evidence that forces exist in the United States today to reverse the conditions that now prevail.

That is a condition in which the economy has awarded one single family — the owners of Walmart stores — 37 percent of U.S. national wealth, virtually the same amount of wealth possessed collectively by the poorest 40 percent of the nation’s population. (These figures, which are well known, were cited by Senator Bernie Sanders [I-Vt.] in a recent interview with Bill Moyers. They are perhaps unjust in intimating that that the Walton heirs make abusive use of their wealth).

In theory, this distribution of wealth affords the family (or let us say the Koch brothers), the possibility of wielding as much electoral power — measured in television political advertising — in national elections than a major part of the total electorate.

I asked in my last column if there is “no way out” of this situation — other than by revolutionary change in the way the economy and political system function, a change which is against the material interests of the dominant business, investor, and existing political classes, who may be expected to fight against any such challenge, or effect alteration in the existing government to prevent it, conceivably by force.

Change has, however, happened in the past, against severe resistance, three times since the Civil War.

During the American “Gilded Age” that accompanied the great economic and industrial boom in the North that followed the defeat of the South in the Civil War, when the transcontinental railroad was built, accompanied by modern industrial development, and the Homestead Act had opened the western states to settlement by offering free federal land to those willing to farm it, Washington during the two Grant administrations experienced notorious corruption, as did the booming cities of the northeast, ruled by manipulative political machines,

The depression of 1873-79 inspired a popular reaction and the first American trade union movement, which rapidly acquired 700 thousand members (in a population of 50 million). Agricultural depression inspired Farmers’ Alliances demanding nationalized railroads, a graduated income tax and “Free Silver” (meaning unlimited coinage).

These popular movements found their leader in the great popular orator and preacher, William Jennings Bryan, who ran for the presidency in 1896 and 1900, losing both times but exciting the enthusiasm of the nation, and in 1900 electing by default the Republican McKinley-Roosevelt ticket.

William McKinley’s assassination within months made Theodore Roosevelt president and inaugurated a period of reforms — of the civil service, anti-trust legislation, regulation of interstate commerce, food and drug inspection and regulation, national resource conservation, and establishment of the nation’s national park system — that shaped much of the United States’ economic and agricultural regulatory framework that survives to the present day.

The first Roosevelt was a romantic nationalist and believer in heroic leadership, contemptuous of class interest. He declared that “a patrician’s politics should be reform, and that reform [means] broad federal powers wielded by executive leadership.”

His nephew, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who confronted the Great Depression, shared and acted upon those beliefs, characterizing the rich who despised and fought him — the “one percent” of the 1930s — as “malefactors of great wealth,” an expression that fit major figures in the election that has just passed, and identifies the vulnerability of democracy to the plutocracy that now exists.

Visit William Pfaff’s website for more on his latest book, “The Irony of Manifest Destiny: The Tragedy of America’s Foreign Policy” (Walker & Co., $25), at www.williampfaff.com.

© 2014 Tribune Media Services, Inc.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.