What Is Going On Inside David Lynch’s Head?

A new memoir offers a unique glimpse into the mind of one of our most visionary filmmakers. Just don't expect him to explain "Twin Peaks."

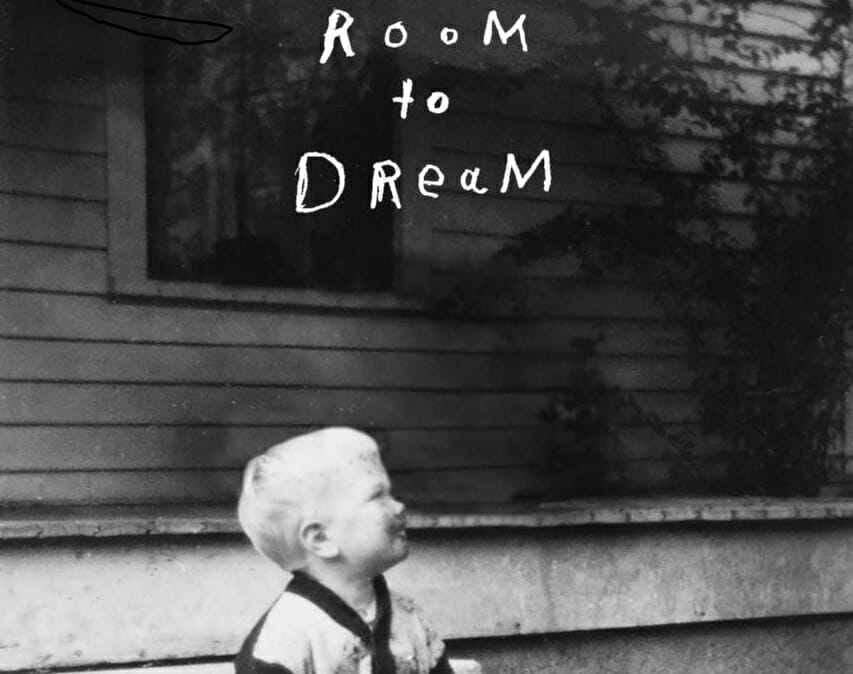

“Room to Dream”

A book by David Lynch and Kristine McKenna

In what is surely as weird as anything in his films or TV shows, David Lynch is now best known for his recent remarks about Donald Trump. On June 25, the three-time Academy Award nominated director of “Blue Velvet” and “Mulholland Drive” and the creator of “Twin Peaks” made headlines, surely in many publications where he’d never had them before, when Trump bragged about his support among Hollywood types, quoting Lynch in The Guardian that Trump “could go down as one of the greatest presidents in history because he has disrupted the thing so much.”

In his own oblique manner, Lynch was saying that Trump has the opportunity to rebuild American politics in a positive way if only because he has destroyed so much of the old edifice. As he later said in an open letter to the president on Facebook, Lynch politely suggested that Trump had taken his words “a bit out of context and would need some explaining.” He was clear that he thinks Trump is “causing suffering and division” but “it’s not too late to turn the ship around.”

“I wish you and I could sit down and have a talk,” he wrote. “Unfortunately, if you continue as you have been, you will not have a chance to go down in history as a great president. This would be very sad it seems for you—and for the country.”

All Trump needs to do, Lynch concluded, “is treat all the people as you would like to be treated.” I don’t think Lynch meant that we all want to be spanked with copies of Forbes magazine, but rather something akin to the lessons of transcendental meditation as propounded by the David Lynch Foundation.

So the man who has shocked audiences with some of the most disturbing and enigmatic images ever recorded turns out to be just a sweet, tousle-haired cosmic muffin. What would David Lynch and Donald Trump talk about? Perhaps Lynch would read Trump this passage from his new memoir and biography, “Room to Dream”: “You can go into the future. It’s not easy, and you can’t do it when you want to, but it can happen.” Oh, to be a fly in the Red Room, hearing Lynch say that to Trump.

The biography portion of “Room to Dream” is by journalist Kristine McKenna; the memoir by Lynch. The authors describe the book as “a chronicle of things that happened. Not an explanation of what those things mean.” So if you pick up this book hoping to discover what the ending of “Twin Peaks” means or what the blue box and blue key in “Mulholland Drive” signify, you’re out of luck. On the other hand, if you’re interested in the thought process of the man responsible for the most fascinating film and television works of the last 40 years, you’ll go through this book like Trump through a Quarter Pounder.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Room to Dream” at Google Books.

In a snotty piece for Premiere in 1997, David Foster Wallace, the guy I would most not want to sit next to on a long flight or be next to in line at the DMV, wrote “… David Lynch is the sort of person you really hope you don’t get stuck next to on a long flight or in line at the DMV or something. In other words, a creepy person.” In fact, the David Lynch presented in “Room to Dream” seems not so much the guy Time magazine called in 1990 “The Czar of Bizarre” as someone you went to school with.

David Keith Lynch was born in 1946 in Boise, Idaho, to a proper Presbyterian family. As a boy he rode bikes, read Mad magazine and was a dedicated Boy Scout. Though his father worked for the Forestry Department, “I never shot a deer, and I’m glad I didn’t.” He once told an interviewer, “When I picture Boise in my mind, I see euphoric 1950s chrome optimism.” If you were wondering where the Eisenhower-era tinge in “Blue Velvet” and “Mulholland Drive” comes from, “The 1950s,” writes McKenna, “have never really gone away for Lynch.”

The family moved to Alexandria, Va., where David finished the eighth grade, learned the trumpet, played first base in Little League, and, while an Eagle Scout, seated VIPs at JFK’s inauguration. Lynch says simply, “My childhood was very happy, and I think that set me up in life. I really did have a great family to give me a good foundation, and that’s super important.”

A childhood friend says, “The darkness in his work surprises me, and I don’t know where it came from.”

The darkness dissipated when, in the summer of 1973, he discovered transcendental meditation. Another friend recalls, “David was a lot darker before he started meditating. It made him calmer, less frustrated, and it lightened him. It was as if a burden had been lifted from him.’ ” A crew member described Lynch as “inquisitive, low-key, very polite, and calm as a Hindu cow.”

TM didn’t dispel Lynch’s dark side; it helped him master it, seeing in the ordinary what others do not see, or perhaps seeing those things in different shades. A dark road is one of Lynch’s most evocative and recurring images, inspiring the opening scene of “Lost Highway” and often used in “Twin Peaks,” and especially in the finale. Lynch recalls driving on an unlit two-lane highway out of Boise: “The only light is from the headlights of the car and it’s pitch-black. It’s hard for people today to imagine this, because there are no roads that are pitch-black, hardly ever.” Flickering headlights skimming the white lines of a road receding into darkness to the ominous aural accompaniment of music from Angelo Badalamenti, Lynch’s favorite composer—it’s a Lynch signature.

Lynch’s career is an object lesson on forging artistic temperament outside trends. “We didn’t have a TV until I was in the third grade, and I watched some TV as a child but not very much.” The man who revolutionized television and is routinely referred as the most avant-garde of American filmmakers wasn’t influenced much by movies: “Movies didn’t mean anything to me when I was a teenager. The only time I went to movies was when I’d go to the drive-in, and there I’d go for making out … why go to the theater? It’s cold and dark and the day is going by outside.”

Lynch spent his days and most of his nights painting and working in other art mediums. McKenna writes, “Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were developing new strategies for bridging the gap between art and life, and conceptualism and minimalism were on the march.” But Lynch and his good friend and fellow artist Jack Fisk worked outside the boundaries of what was covered in Artforum. “For them,” McKenna writes, “art was a noble calling that demanded discipline, solitude, and a fierce single-mindedness; the cool sarcasm of pop and cocktail-party networking of the New York art world had no place in their art-making practices.”

The counterculture passed him by. The man whose films would later be described as phantasmagorical never did drugs, according to a friend: “He didn’t need them.”

Lynch’s parents deserved some kind of medal. They didn’t understand their son, but steadfastly supported his ambitions. When Lynch arrived at the Pennsylvania School of Fine Arts, the country’s oldest art school, it was a backwater, “but it was exactly the launching pad he needed.”

Film, which began to interest him in his 20s, became another canvas for his ideas. In 1970, Lynch received an unexpected grant from the American Film Institute and, with his wife Peggy and baby daughter Jennifer, left for Los Angeles. Among his classmates were future filmmakers Terrence Malick and Tim Hunter, who would later direct episodes of “Twin Peaks.” After several experimental films, Lynch completed “Eraserhead” (1977), which became a cult favorite and one of the first mainstays of the midnight movie circuit.

A summation of “Eraserhead’s” plot serves no purpose; suffice to say a man with incredibly frizzy hair (Jack Nance) lives in a blighted postindustrial (post-apocalyptic?) city and, to the accompaniment of Fats Waller organ music, tries to deal with the horror of his newborn deformed mutant baby. The film, McKenna writes—correctly I think—is “a magisterial film that operates without filters of any sort, ‘Eraserhead’ is pure id.”

Perhaps the most amazing fact of Lynch’s career is that his big break came from Mel Brooks. After seeing a screening of “Eraserhead,” Lynch recalls, “The doors burst open … and Mel comes charging toward me, embraces me, and says, ‘You’re a mad man. I love you!’ ” Brooks, as a producer, chose Lynch to direct “The Elephant Man,” the story of John (actual name Joseph) Merrick, the deformed sideshow freak who was rescued by a doctor, Sir Frederick Treves.

Brooks stuck with Lynch despite near-violent resistance from Anthony Hopkins (who played Treves to John Hurt’s Merrick). One of the best photos in “Room to Dream” is a double-page spread of “The Elephant Man” crew with the most unlikely film collaborators of our time, David Lynch and Mel Brooks, grinning into the camera.

The film was given a boost by a rave review from The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael: ” ‘The Elephant Man’ has the power and some of the dream logic of a silent film…”—perhaps the first time the phrase dream logic was used in connection with Lynch. (Kael had praised the screenplay while working for Paramount.)

The big budget misfire of the sci-fi epic “Dune” (1984), the only film taken away from him during the editing process, was followed by the dark starburst of “Blue Velvet” (1986), which Kael called “the work of a genius naïf. … When you come out of the theater after seeing David Lynch’s ‘Blue Velvet,’ you certainly know that you’ve seen something. You wouldn’t mistake frames from ‘Blue Velvet’ for frames from any other movie.” Especially at the beginning where a college student (Kyle MacLachlan) finds a severed human ear in an empty lot. From there, every plot turn reveals something more unsettling.

In the most famous scene, emblematic of the film as a whole, Dean Stockwell, in white face makeup holding a flashlight on his face, lip-syncs Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams.” (Lynch, who loves Orbison, would use another of his classics to great effect in “Mulholland Drive.”)

“Blue Velvet” is a mystery solved but not resolved. Lynch shocked audiences by mining the dark from the mundane of American life, the evil of banality.

Lynch’s other features—“Wild at Heart” (1990); “Fire Walk With Me” (1992), a prequel to “Twin Peaks”; “Lost Highway” (1997), which has perhaps the most disquieting scene in a Lynch film where Bill Pullman encounters a corpse-like Robert Blake at a party; the lovely but little-seen “The Straight Story” (1999), “Mulholland Drive” (2001), and “Inland Empire” (2006)—all found support with the college/art house moviegoers. In this century, as the art house scene has faded, the internet has picked up much of its audience.

At a party, Lynch said to Steven Spielberg, “You’re so lucky because the things you love millions of people love, and the things I love thousands of people love.” Spielberg replied, “David, we’re getting to the point where just as many people will have seen ‘Eraserhead’ as have seen ‘Jaws.’ ”

That’s an exaggeration, but the point survives it: The internet and streaming services have given Lynch a global audience not only for his films and “Twin Peaks” but many short films on a myriad of topics, for rock videos (Chris Isaak and Michael Jackson), and numerous commercials, including “Lady Blue Shanghai,” a killer 16-minute internet promotion for Dior starring Marion Cotillard.

If you’re intrigued by David Lynch but have found his work to be other dimensional, “Room to Dream” might be your portal.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.