What Happened to the Female Directors of Hollywood? (Part 3)

Those who emerged between 1966 and 1983 challenged the prevailing image of the central hero and marginal heroine by creating a "countercinema."

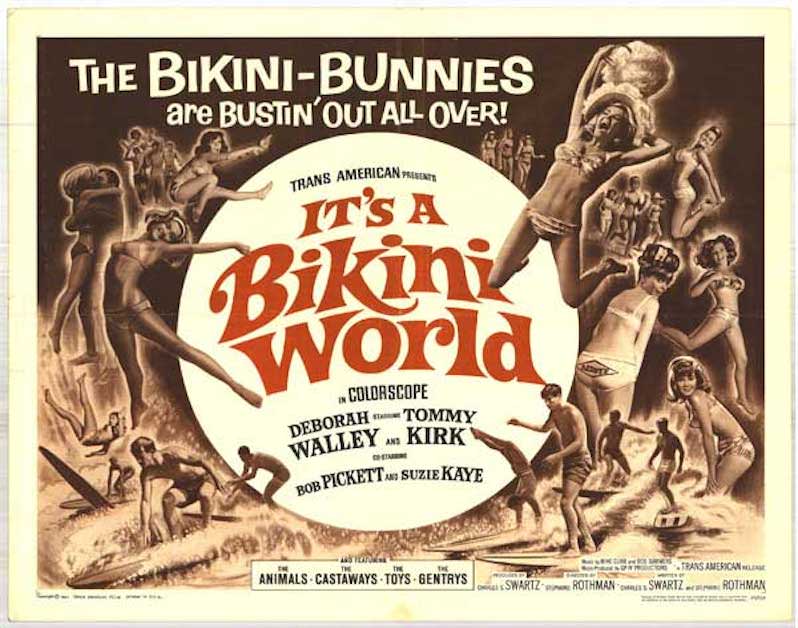

Stephanie Rothman’s “It’s a Bikini World” (1967) turned social and cinematic conventions on their heads. (YouTube)

Editor’s note: In October 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) began investigating Hollywood’s gender gap. Before the EEOC concludes its mediation process, Truthdig contributor Carrie Rickey considers the historic accomplishments of women behind the camera, how they got marginalized and how they are fighting for equal employment.

This five-part Truthdig series is published in partnership with Women and Hollywood and Chicken & Egg Pictures. Click here to read Part 1, here for Part 2, here for Part 4 and here for Part 5.

As Ida Lupino directed “The Trouble with Angels,” in 1966, the ground was shifting in Hollywood. A new generation of moviemakers, film-school graduates such as Francis Ford Coppola, Stephanie Rothman and Martin Scorsese were knocking on boardroom doors. But the occupants of those boardrooms were being booted, replaced by executives from the parking-lot giants and petroleum companies that had taken over Warner Brothers and Paramount.

The old order was history. The new order struggled with corporate change and with the social and political revolutions rocking the nation, from the antiwar movement to “women’s libbers,” as the popular press dubbed feminists.

Many women, feminist or not, watched films like “Easy Rider,” “M*A*S*H,” and “The Wild Bunch,” demanding to know why women on screen were sex objects, not characters. They asked, “Where are the women on screen?” Fewer asked, “Where are the women behind the camera?”

Even fewer were aware that this was an era during which the window for female filmmakers was open wide enough for more than one woman to crawl through. The female moviemakers that emerged between 1966 and 1983 challenged the prevailing image of the central hero and marginal heroine by creating a “counter cinema.” Theirs were films that actively criticized the conduct of male characters and cast females in the lead.

From the debut of Rothman, the subversive exploitation filmmaker, with “It’s a Bikini World” in 1967, to that of Kathleen Collins, the first African-American woman to make a feature film, in the early ’80s, a clutch of female filmmakers came in through the back door. So what if Jean-Luc Godard said that all he needed to make a movie was “a girl and a gun”? In the 1960s through the early 1980s, his female counterparts proved that all a gal needed was a script and an Arriflex (movie camera).

This new generation of female directors came from film schools, art schools, theater and comedy clubs. As was the case with Lois Weber and Ida Lupino, many of the new filmmakers were performers, like Elaine May. Rothman, Collins, Amy Heckerling, May, Joan Micklin Silver and Claudia Weill made a collective splash in the United States, while across the Atlantic their European counterparts, Chantal Akerman, Agnès Varda and Lina Wertmüller, likewise made waves.

In 1965 Rothman became the first woman to win a Directors Guild of America fellowship. That same year, Roger Corman, the exploitation-movie producer who hired Coppola, Scorsese and Jonathan Demme for their first features, tapped her as his assistant. At the time it was rare for a woman to secure work behind the camera.

Rothman was a Jill-of-all-trades. She rewrote scenes for movies in production, scouted locations for those in the pipeline, cast actors and edited final cuts. For movies with continuity problems, Corman had her direct new scenes. Within a year he financed her first feature, “It’s a Bikini World” (1967), a singular feminist beach movie, starring Deborah Walley as a young woman who rejects a handsome surfer for his chauvinism, inspiring him to assume a different persona.

From 1967 to 1974, Rothman made six female-driven genre films, among them “Student Nurses” (1970), “The Velvet Vampire” (1971) — the first feminist vampire film — and “Group Marriage” (1973). These films satirized genre conventions and subverted male moviegoers’ expectations of submissive women. Despite her productivity and box office success, Rothman was one of the few Corman discoveries who did not go on to studio filmmaking.

Elaine May, half of the Nichols-and-May comedy duo with Mike Nichols, made her debut as a writer/director/star with “A New Leaf” (1971), one in a handful of rueful satires that look askance at men and what now is called male privilege. In “Leaf,” Walter Matthau is a gold digger hunting for a millionairess; in “The Heartbreak Kid” (1972) Charles Grodin a cad who proposes marriage to Cybill Shepherd while on his honeymoon with Jeannie Berlin; in “Mikey and Nicky” (1975), John Cassavetes and Peter Falk are low-level mobsters and friends, one hired to kill the other.

Also a prolific screenwriter, May wrote “Heaven Can Wait” (1978), for which she landed an Academy Award nomination, and script-doctored “Tootsie” (1982). After her last feature, “Ishtar” (1987), the prescient comedy about two entertainers who get involved on opposite political sides in the Middle East, she wrote well-received scripts for “The Birdcage” (1996) and “Primary Colors” (1998).

During the mid-1970s, European imports by female directors had unusual currency. From Italy there were Lina Wertmüller’s “Swept Away” (1974) and “Seven Beauties” (1975), films about class war and that between the sexes. For “Beauties,” Wertmüller became the first woman to receive an Oscar nomination for best director. From Belgium in 1975 came Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Bruxelles,” examining the tedious “woman’s work” of a full-time mother and part-time prostitute. From France there was Agnès Varda’s “One Sings, the Other Doesn’t” (1977), about Parisiennes united and marching for civil and reproductive rights.

Back in the United States, Barbara Kopple made her debut with “Harlan County, USA” (1976), an intimate chronicle of Kentucky coal miners who refuse to sign a contract that has no-strike clause. With obvious sympathy for the miners and their families, the film had an unprecedented urgency. By rejecting the objective approach of other nonfiction filmmakers, the film helped change the course of American documentary filmmakers who likewise embraced a partisan approach to their subjects. The film won Kopple an Academy Award and kicked off a 40-year career that spans the Oscar-winning “American Dream” (1990) and “Miss Sharon Jones!” (2015).Claudia Weill began her directing career in documentary as the co-director (with Shirley MacLaine) of the China chronicle “The Other Half of the Sky: A China Memoir” (1975). Her first feature, “Girlfriends” (1978), a micro-budgeted movie about a young photographer in Manhattan, attracted attention and earned her a studio movie, “It’s My Turn” (1980), a feature starring Jill Clayburgh and Michael Douglas.

Also in 1975, Joan Micklin Silver made her directorial debut with “Hester Street,” a droll comedy about a power struggle in the marriage of Jewish immigrants to the U.S. in the early 20th century, imaginatively filmed like a silent movie. Micklin’s subsequent ensemble films, “Between the Lines” (1977) and “Chilly Scenes of Winter” (1979), held out the promise of a prolific career. Yet although she would make the superb feature “Crossing Delancey” (1988) (like “Hester Street,” a movie about the twin pulls of assimilation and tribe), most of her post-1970s work was for television, as was Weill’s.

As in 1920, in 1980 the window for proven women filmmakers in the U.S. abruptly closed. Ironically, both years were high-water marks for the women’s movement. In 1920 women won the right to vote. In 1978, women marched on Washington for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and during the following year, membership in the National Organization of Women reached an all-time high. Both in 1920 and 1980, Republican presidents replaced progressive Democrats.

Why were the opportunities for female filmmakers diminishing just as women were gaining political clout? This question dogged a group of women directors who met each other at the Director’s Guild of America (DGA) meetings in 1979. Now known as the “Original Six,” these activists — Susan Bay Nimoy, Nell Cox, Joelle Dobrow, Dolores Ferraro, Victoria Hochberg and Lynne Littman — formed the Women’s Steering Committee (WSC) of the DGA. Like many professional women, the Six, who worked primarily in documentary and television, wanted to reconcile the disconnect between the passive, mostly decorative, women on screen with the dynamic women they knew in real life.

With the support of Guild President Michael Franklin, they collected statistics and found that among all the directors in movies and television, only 0.5% were women. (By 1980, among practicing attorneys, just 12 percent were women.)

That same year that Ronald Reagan was elected president, the Six began meeting with entertainment executives in the hopes that they would voluntarily hire qualified women. “I remember the [1980] meeting when those women revealed those embarrassing, shameful statistics,” said TV executive Norman Lear. “But then everybody went back to work, and I never saw any evidence of improvement.” The government was unlikely to intercede, as the Reagan administration neither was an advocate of unions nor did it support the Equal Rights Amendment, which lost by six votes in the House of Representatives in 1983.

While the Original Six continued to strategize with the DGA for ways to make Hollywood more inclusive, four rookies — and one high-profile actress-turned-filmmaker — won attention for their debut films.

After a decade making shorts and documentaries, Gillian Armstrong made the auspiciously titled “My Brilliant Career” (1979) with support from the Australian Film Development Corp. and the New South Wales Film Corp. A period piece based on the autobiographical novel by Miles Franklin (who was often compared with Louisa May Alcott), “Career” introduced an electrifying actress named Judy Davis as a brash young woman from the outback sent to the city to polish her rough edges. Sybilla, the independent-minded young woman who seeks her own fortune, was the first of many Armstrong characters to live life on her own terms. Among Armstrong’s other films are “Mrs. Soffel” (1984), “High Tide” (1987), “Little Women” (1994) and “Oscar and Lucinda” (1997), the last of which gave Cate Blanchett her first movie lead. Armstrong remains an active filmmaker.

In 1980, Kathleen Collins, playwright, university professor and film editor, became the first African-American woman to write, produce and direct a feature film, “The Cruz Brothers and Mrs. Malloy,” an adaptation of a Henry Roth short story, She is better known for “Losing Ground” (1982), her second feature, about a philosopher married to a painter, and their conflicting ways of looking for an ecstatic experience. Collins died in 1988 of breast cancer.

A graduate of New York University and the American Film Institute, Amy Heckerling made her feature film debut with the studio-released “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” (1982), a multi-character story of high schoolers whose paths cross in class and at the mall where many of them work. Aiming for both the comedy and angst of adolescence, Heckerling elicited memorable performances from newcomers such as Phoebe Cates, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Sean Penn and Forest Whitaker. She would go on to make other movie classics, including “Look Who’s Talking” (1989) — the first female-directed movie to gross over $100 million — and “Clueless” (1995). She remains an active filmmaker. After Penelope Spheeris received her degree from the UCLA film school in 1973, she married her love of music and that of film by founding Rock and Reel, producing music videos before they were a thing. In 1975 her friend Lorne Michaels asked her to teach comedian Albert Brooks to make film shorts for a new show called “Saturday Night Live,” and she produced Brooks’ first feature, “Real Life” (1979). Spheeris made her directorial debut with “The Decline of Western Civilization” (1981), a deadpan documentary about punk music and musicians. For Roger Corman, she made “Suburbia” (1984), a fictional feature about punk rockers who squat in abandoned homes. Spheeris later wrote for the television show “Roseanne.” She directed “Wayne’s World” (1992), “The Beverly Hillbillies” (1993) and “The Little Rascals” (1994). She also remains an active filmmaker.

In 1968, singer and actress Barbra Streisand had hoped to follow up “Funny Girl,” her film debut, with a movie based on the Isaac Bashevis Singer story “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy,” about a Jewish girl who disguises herself as a boy to study Talmud. After years of being told that the story was too ethnic, that she was too old to play the title role and that studios wouldn’t trust an untried filmmaker with a $14 million budget, Streisand made a deal with United Artists to star and direct. Released in 1983, “Yentl” earned four Oscar nominations, $40 million dollars and a grudging respect for Streisand’s tenacity. Streisand would direct two more features, “The Prince of Tides” (1991) and “The Mirror Has Two Faces” (1996). She is now in pre-production for “Catherine the Great,” a biopic about Russia’s scarlet empress.

The good news during this phase of film history was that some female moviemakers, most of them fresh from film school, were making incremental progress. After all, in 1981, Heckerling had been hired by a major studio. Still, the previous year, Warner Brothers stipulated that future director Nancy Meyers had to be accompanied by a man to the set of “Private Benjamin” (1980) — and she was a producer and screenwriter of the film!

The bad news was that the Original Six and DGA were stalled in getting studios to voluntarily comply in hiring more women. DGA President Michael Franklin was convinced that legal action should be taken. Because the Original Six could not afford legal costs, in 1983 the DGA filed a class-action suit against Warner Brothers and Columbia Pictures on behalf of the underemployed women. It was the first time female filmmakers used civil rights laws to challenge gender discrimination.

With cautious optimism, the Original Six awaited the judge’s ruling.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.