We’ll Always Have Paris

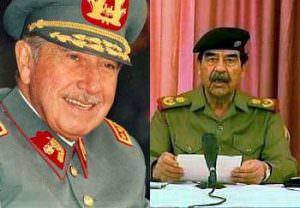

For former "60 Minutes" producer Barry Lando, Moammar Gadhafi's recent visit to France raised some important questions about the West's attitudes toward tyrants. Just whom should we embrace and whom should we flatten with a bit of shock and awe?

France is seething over the official visit of Moammar Gadhafi to Paris — a landmark affair, considering that President Nicolas Sarkozy’s invitation was the first such offer from a Western leader since Gadhafi’s notorious rupture with the West in the 1980s.

Unfortunately, the arrival of the Libyan tyrant happened to coincide with World Human Rights Day. But the predictable political uproar in Paris raises as many questions about the hypocrisy of those who criticize Sarkozy for playing host to Gadhafi as it does about the morality of the event itself. In fact, the issue resonates far beyond the borders of France.

Not only was Gadhafi received formally — if coolly — at the Elysees Palace, but the onetime international pariah, whose secret services blew a couple of packed airliners out of the skies, was invited to address the French National Assembly — an event that the majority of assembly deputies boycotted. He was even allowed to pitch his heated Bedouin tent in the garden of the mansion where foreign dignitaries are traditionally put up.

The French government was quick to point out that Gadhafi is no longer the notorious revolutionary leader he once set out to be. He has renounced his nuclear weapons program, declared he no longer supports terrorism, and informed the French National Assembly that the violent era of national liberation movements was over.

“If we don’t welcome countries that are starting to take the path of respectability, what can we say to those that leave that path?” Sarkozy explained before the visit.

The trip was notably sweetened by Gadhafi’s signing agreements to purchase more than $14 billion in French products, from the Airbus to a nuclear reactor (for water desalination) to advanced jet fighters. Industrialists and oil companies in France are salivating over further possibilities.

Just the same, many leading French — including some from Sarkozy’s own government — were outraged. Bernard Kouchner, a longtime defender of human rights, now minister of foreign affairs, declared that “by happy coincidence” he would be unable to attend the official dinner because of a prior diplomatic engagement.

France’s Secretary of State for Human Rights Rama Yade said, “Col. Gadhafi must understand that our country is not a doormat on which a leader, terrorist or not, can come to wipe the blood of his crimes off his feet.”

Such firestorms over the ethics of dealing with this or that head of state regularly flare up in the West. Just a few days ago, for instance, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown raised African hackles by boycotting the summit of European and African leaders in Lisbon because of the presence of Zimbabwean tyrant Robert Mugabe.

But the issue raises a series of tough questions that cut to the heart of what international relations should be all about.

Which heads of state should be beyond the pale and why? Which tyrants’ visits should we get upset about? Which should we accept? Which — if any — leaders should we spurn? Which should we talk with?

Mao’s China, for instance, was the empire of evil par excellence — until Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger finally traveled to Beijing and pronounced its leaders fit for international consumption. Certainly China is not the repressive regime it was under Mao; on the other hand, does anyone claim that the country is a beacon of democracy, either at home or abroad? Witness its backing of Iran and Burma and Robert Mugabe.

In their dealings with the world, the Chinese tend to ignore the burning issues of morality and human rights that, in theory, are supposed to influence the politics of the West. What counts is what leader has the resources the Chinese need, not the way he runs his country.

But do Western leaders have a different approach when vital national issues are concerned?

Gadhafi, for example, was excoriated by the West for his support of terrorism and his nuclear ambitions. For years, however, American leaders have exchanged warm red-carpet visits with Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf, whose secret police covertly backed al-Qaida and the Taliban, and whose top nuclear scientist, Abdul Qadeer Khan, peddled nuclear technology to Libya, Iran and North Korea — almost certainly with the knowledge of leading Pakistani officials. Khan’s clandestine network may even have had dealings with other countries. We don’t know, since Musharraf continues to shield the scientist, who is still a national hero.

One gets the impression that many of the international pariahs tend to rule over smaller countries that lack huge resources.

The leaders of Burma, for instance, are considered untouchables here in France and certainly throughout most of the rest of the West. They run a corrupt, brutal regime, murdering or imprisoning hundreds of civilian opponents. By the same standards, when should Vladimir Putin be removed from the international A-list?

Maybe we need some kind of score card, perhaps on a per capita basis. How many journalists or other opponents, for instance, have to be assassinated, how many elections have to be trumped up, how much money has to be stolen, before it’s considered immoral to deal with a head of state?

North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Il, with his strange despotic ways, sprawling prison camps and starving population, was long considered the epitome of despotism. Definitely beyond the pale: part of the “axis of evil” — a “pygmy,” George H.W. Bush called him. Now the New York Philharmonic is on its way for a round of concerts in North Korea, with blessings from the White House.

But let’s get down to basics. If two leaders want to talk face to face, one of them has to travel. Perhaps an international body could prepare a sliding scale of formal honors that would or would not be permitted, depending on the moral rating of the visiting head of state. Are red carpets acceptable at the airport? Reviewing an honor guard? Are state dinners OK? How many courses? What about state dinners with entertainment? How about laying a wreath at the local war memorial? An invitation to address the national assembly or congress? A visit to the Crawford ranch?

Of course, somewhere you have to draw the line, right? Another Hitler, for instance. Except that for most of the ’30s, many of America’s leading industrialists — and many political leaders — were among Hitler’s admirers and supporters. For instance, in 1938 Henry Ford, on his 75th birthday, received one of Germany’s highest decorations from the Fürher.

How about Josef Stalin — a despicable tyrant who probably killed more of his own people — 20 million, it’s estimated — than did Hitler. Back in 1943, Life magazine dedicated an entire edition to the Soviet ruler. An in-depth condemnation of his bloody regime? No way. The entire issue was a paean to the patriotism, the valor, the economic pioneering and planning of Stalin — the Father of the Russian People, America’s great ally against Hitler. The photographs and articles, which included lengthy assurances of Stalin’s benign postwar intentions toward Europe, could have come straight from The Daily Worker.

A final question: Gadhafi claims to have turned his back on his violent past, but how to handle other controversial heads of state — despised in much of the world — who show little inclination to change and little remorse? A leader, for instance, who ordered his forces to invade another nation, causing the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, the injury and exile of millions more; a leader who condones torture by his intelligence agencies and secretly dispatched prisoners to be brutalized by the secret services of other countries, at the same time locking up hundreds of others for years on end without any charge.

Do you invite him to the Elysees for dinner? Does he get to set up his heated tent in the garden of your official guest residence?

Barry Lando is the author, most recently, of Web of Deceit: The History of Western Complicity in Iraq, from Churchill to Kennedy to George W. Bush.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.