Welcome to Alphaville, Avoid the Ghetto

The world we see through our smartphones is a curated world, and its horizons are constricting, rather than expanding. The world we see through our smartphones is a curated world, and its horizons are constricting, rather than expanding.

In the 1965 film “Alphaville” by Jean-Luc Godard, a dystopian, futuristic society is governed by a sentient but unfeeling computer called Alpha 60. Emotion, opinion and free will have been outlawed under pain of death, and the human condition has been reduced to the ruthless calculus of Alpha 60’s circuit board. This regime is enforced, in part, by the presence of a “bible” in every home — a networked dictionary of permitted words that continually updates itself by expunging any reference to thoughts or ideas that may trigger an emotional response, let alone provoke a revolution.

A half-century later, the cinematic trope of the evil, dictatorial computer has become so well worn as to be a parody of itself (have you seen “TRON: Legacy”?), but most of us carry Alphaville bibles around in our pockets and purses. Yes, they might give us the gift of Angry Birds and allow us to share pictures of our lunch with our 500 closest friends. In some cases, they even help people to coordinate revolts and revolutions. But make no mistake: The world we see through our smartphones is a curated world, and its horizons are constricting, rather than expanding. Though they’re often billed as modern-day Diogenes’ lamps, outshining the light of day with the light of truth (or “augmenting reality,” in contemporary geekspeek), they would be better understood as corporate-sponsored guidebooks to our own lives, keeping us on the prescribed path and off the road less traveled.

Theoretically, there’s no reason that our smartphones, tablets, other devices and services shouldn’t live up to the hype, putting the world at our fingertips and giving us the ability to read or write any piece of information or connect with any person. The technology is certainly up to the task. The problem is that the manufacturers of these technologies, and the states that regulate them, often have their own agendas, and these are integrated into our devices, and our lives, at such a deep level that we can’t even see it — until it’s too late.

There have been several red flags over the years, though these have often seemed to be the exception, rather than the rule, or of minimal impact to everyday people. Verizon’s decision in 2007 to block text messages from the abortion rights group NARAL to the group’s own members was one. Apple’s stringent, and at times anti-competitive, control over the applications we can install on our iPhones and iPads is another (there’s a reason we call it “jailbreaking” when we choose to install our own software on the devices we’ve purchased). The FCC’s decision not to require “net neutrality” on mobile devices, essentially giving carriers veto power over our Internet browsing, is yet another. Cyberlibertarians and free speech advocates may have bridled at these overreaches, but most people just shrugged, if they heard about them at all. With so much information to choose from, who cares if a little bit of it is off-limits? Infinity minus a million is still infinity.

The thing is, Alphaville is closer than we might think. With the advent of high-speed mobile information networks, the Internet is no longer something found in a box on our desks; it’s all around us, and there are increasingly few aspects of our lives that are not filtered through — or even supplanted by — its circuitry (a recent survey found that one in three Americans would sooner give up sex than smartphones). In the not-so-distant future, it may be integrated into our furniture, our clothes and even our bodies. This means that it’s no longer just our surfing and texting habits that are susceptible to censorship — it’s our lives themselves.

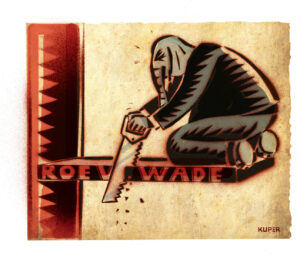

A few recent developments point to the troubling potential consequences of this situation. In August, Apple released the newest model of its massively popular iPhone, equipped with an onboard, voice-activated intelligent agent named Siri. Ask Siri anything, from “What’s the next showing of ‘Alphaville’?” to “Where can I hire a prostitute?” and she will provide up-to-the-minute, location-specific recommendations based on a quick analysis of Internet resources. In other words, she’s a search engine for nearly every aspect of our daily lives. Yet, for some reason, for the first few months after she appeared on the market Siri was unable to provide iPhone users with access to abortion services. Some iPhone owners even reported being diverted to adoption services instead. In Siri’s universe, apparently, Roe v. Wade never happened.

After an uproar from free speech and women’s rights groups, Apple apologized for the “glitch,” claiming that it was accidental, rather than ideological, in nature. Today, the problem appears to have been fixed. Yet the very fact that such a problem could make it to market, and remain unfixed weeks after it was first reported on, betrays at the very least a shameful disregard on the part of Apple for the rights and well-being of its customers. It also raises the question: What else is Siri not telling us? Apple’s market nemesis, Microsoft, has had its Alphaville moments, as well. Just last week, the company filed a patent for Windows Mobile navigation software that would allow its users to avoid “traveling through an unsafe neighborhood.” Reporters and pundits have been quick to dub this technology the “avoid the ghetto” option, and snarky though it may sound, there’s a reason the name has stuck. While there’s no question that the technology would certainly be of value to many Windows Mobile users, it comes at a severe cost: painting entire neighborhoods, and their residents, as undesirable. The technology also contains other hidden biases, assuming that Windows Mobile users are from the well-to-do segment of society for whom high-crime neighborhoods are simply nuisances to be avoided, rather than social challenges worth addressing (let alone viable homes). This assumption is clearly ideological, rather than logical; according to data published by Nielsen last year, blacks and Latinos, who disproportionately inhabit “unsafe neighborhoods,” are far more likely than others to use smartphones.

Even worse than the smug bias inherent in Microsoft’s navigation patent is the potential social outcome of its implementation. By giving some technology users the opportunity to avoid neighborhoods based on economic factors, the company would actually exacerbate the neighborhoods’ problems, preventing potential shoppers from spending their money there and hermetically sealing the inhabitants inside an invisible ghetto wall. This kind of technology is typically called “social engineering,” and is fundamentally no different from Robert Moses’ infamous parkway bridges. Whether Microsoft intends this outcome or not is irrelevant; as in Apple’s case, the company’s blindness is almost as damning as malice.

As these technologies become ever more vital for an ever-larger segment of the American public, the threat of “life censorship” becomes ever greater as well. We could address these problems by creating laws and policies that would require mobile technology providers to lower their proverbial garden walls, lift their proverbial kimonos and allow consumers to exercise a greater degree of knowledge and control over the flow of information they transact. Unfortunately, our Congress is presently too busy promoting pro-censorship legislation like the Stop Online Piracy Act. I think you can guess where that path leads.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.