We Locked ’Em Up, Threw Away the Key

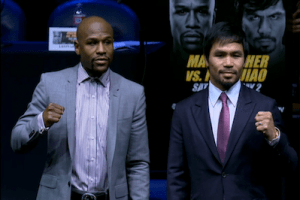

You had to be there! Jesse Jackson, in the company of the real life Rubin "Hurricane" Carter at a jailhouse screening of "The Hurricane" before a mostly black and brown audience whose future prospects seemed as drab as their faded inmate uniforms. Rev. Jesse Jackson, left, listens to boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter during a news conference in 2000 at the North County Correctional Facility in Castaic, Calif. (AP/Damian Dovarganes)

Rev. Jesse Jackson, left, listens to boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter during a news conference in 2000 at the North County Correctional Facility in Castaic, Calif. (AP/Damian Dovarganes)

This article was originally published by the Los Angeles Times on March 7, 2000. Middleweight boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter died Sunday.

Jesse Jackson for president. Absurdly late, I know, but his voice is what has been missing in this campaign season.

I’m aware of the cynicism toward the man that resides in the media and a part of the electorate. But after observing him in front of an audience of inmates the other day at the Los Angeles County Jail in Castaic, I see him as the one public figure still willing to address the great intractable issue that we face: Race.

You had to be there! Jackson, in the company of the real life Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a former middleweight boxing contender who spent 20 years in prison for a murder he did not commit, at a jailhouse screening of “The Hurricane” before a mostly black and brown audience whose future prospects seemed as drab as their faded inmate uniforms.

But when Jackson stood before them, alongside the now free and still vibrant 63-year-old Carter and led the prisoners in chanting, “Keep hope alive,” that overused phrase seemed as inspirational as the Sermon on the Mount. They are words intended for the least among us, the forgotten and discarded, and the Rev. Jackson extended the Almighty’s hand.

The optimism of the movie’s tale of survival, embodied in this man Carter, who had endured for so many years to emerge strong and who bore a message of self-improvement under the direst of circumstances, caught the eyeballs and ears of guards and prisoners alike. Carter talked of the guards being trapped in the same system and cautioned the inmates to follow the rules and not to doubt “their authority to bop you.”

But he also talked about using the jail as the only school they were likely to enter at this point in their lives. “Don’t let this be dead time,” he said, urging them to learn to read and recalling his own immersion in the works of Dostoevsky and in the example of Nelson Mandela during his long, tough prison time. At the end of the screening, following a thunderous ovation, Carter pleaded with the men to “go through the small door to the large room” and to “be in jail but not let the jail be in you.”

Jackson and Carter had taken this show to the Cook County Jail in Chicago the week before, and once again they were screening this movie about redemption to hundreds of the almost 2 million prisoners whom the rest of society has doomed to the hell of more or less permanent incarceration. Many in the audience were still in the early stages of recycling through the prison system, America’s answer to its failure to deal with its legacy of racial oppression.

When Jackson asked those who were repeat offenders to stand, many rose to their feet under the nervous watch of the suddenly alert guards lined against the walls. When Carter said, “I was innocent, but don’t jive me; most of you did the crime,” there were sad nods of agreement.

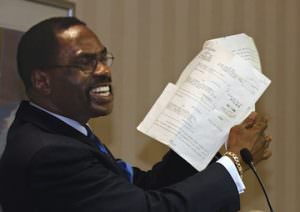

Jackson ticked off the dismal statistics of America’s prison growth industry: almost a third of young black men caught in the legal system and more in jail than in universities, statistics so shocking in their implications that they are barely comprehensible. We have 500,000 more prisoners than China, which has four times our population, and yet we complain about its human rights record.

Of the almost 2 million people in jail–as Jackson goes on in his rhythmic indictment of a system created by politicians who have abandoned any notion of rehabilitation–1.2 million are incarcerated for drug use and other victimless crimes. These are the prisoners of the drug war waged mostly in the ghettos. These are the people who need medical help, psychiatric treatment, education, jobs–not endless prison time.

Jackson excoriated the inequities of a criminal justice system brought vividly to life by Denzel Washington’s brilliant performance in “The Hurricane.” Despite the nit-picking of critics, the movie reminds us that it took a courageous federal judge to undo the woeful miscarriage of justice condoned by the entire New Jersey political and judicial system.

This country has used a prison-based apartheid system as an alternative to truly integrating its largest racial minorities into the mainstream of educational and economic opportunity. While politicians scramble to build more prisons than schools and pay guards more than teachers, Jackson is the one political leader still willing to cry in shame for the discarded young.

At moments like that, he is indeed The Reverend who uses religion to unify rather than divide, and the justified inheritor of the mantle of his mentor, Martin Luther King Jr.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.