We Are All Liberians Now

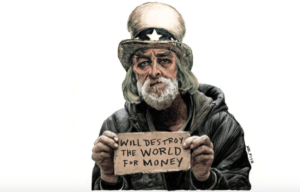

Ebola is a nightmare disease that travel restrictions cannot keep out. Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Ebola is a nightmare disease that travel restrictions cannot keep out. The correct response should be urgent concern — not panic — and an all-out crusade to extinguish the West Africa outbreak of the deadly virus at its source.

This is essentially the Obama administration’s strategy. But it needs to be explained more effectively to the public, and it needs to be part of a much bigger coordinated effort by developed nations. Everyone has a stake in this. As far as Ebola is concerned, we are all Liberians.

Following the death of Thomas Eric Duncan — the first victim in this country — officials announced there will be additional screening of travelers from West Africa at the John F. Kennedy, Newark Liberty, Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson, Chicago O’Hare and Washington Dulles international airports. Passengers arriving from affected countries will have their temperatures checked, and anyone with a fever will be isolated and evaluated by medical personnel from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The step was meant to ease public fears — and perhaps to silence critics who foolishly have advocated such radical measures as banning all travelers from the Ebola region. But the new protocol wouldn’t have kept Duncan out of the country, nor will it bar entry to other individuals infected with the virus.

Duncan, a native of Liberia who traveled to Dallas in hopes of attending his son’s high school graduation, had an itinerary that connected through Europe; his flight to Dulles originated in Brussels and thus would not have been subject to enhanced screening. And since there is usually a latency period of about a week between infection with the Ebola virus and the appearance of symptoms, Duncan is not believed to have had a fever when he landed. Even if he had faced extra scrutiny, presumably he would have been waved through.

In the worst-affected countries, there is screening to keep potentially infected individuals from boarding outbound international flights. Despite these efforts, however, it is reasonable to assume there could be others who came into the United States unknowingly carrying the virus.

And let’s be realistic: Imagine you’re a Liberian or a Sierra Leonean, you think there might be a chance you’ve been infected with Ebola, you have no symptoms, and you can afford a plane ticket. Where would you rather be examined and, if necessary, treated? In a leading medical center? Or in a field hospital in the middle of the hot zone?

Still, any kind of knee-jerk attempt to ban all travel from countries where the outbreak is raging would be disastrously counterproductive.

Remember that Ebola doesn’t care what color passport its human host happens to be carrying. Since the virus is spread through contact with bodily fluids, health care workers are at much greater risk than others. This means that Western doctors, nurses, missionaries and others who went to West Africa to try to quell the outbreak would also have to be kept from leaving the hot zone. You can’t send health workers in if you have no way to get them out — and the same holds true for the 4,000 U.S. troops that President Obama plans to send to the region.

Moreover, any Western attempt to effectively quarantine the epicenter countries would inevitably put much greater pressure on the fragile public health system of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, which thus far has managed to isolate and contain the disease. In the event of a serious outbreak there, Ebola could become endemic in West Africa. This cannot be allowed to happen.

The only solution is to quash the outbreak now while we’re still talking about thousands of cases rather than hundreds of thousands. Sending in the troops may not sound like a great idea, given the many other missions assigned to the U.S. military, including the new war against the Islamic State. But it’s the only idea I’ve heard that might work.

“This is not a small effort, and this is not a short period of time,” Gen. David Rodriguez, commander of U.S. forces in Africa, said this week. The troops, based in Liberia, will build 17 new Ebola treatment facilities and seven testing labs. There will inevitably be some risk of infection, especially to the trained personnel at the testing centers. But the alternative — doing nothing — is much riskier.

The Obama administration needs to be much better at communicating a simple fact: Right now, you and I are essentially in no danger of contracting Ebola. But if we don’t act, there will be a danger — and it won’t go away.

Eugene Robinson’s e-mail address is eugenerobinson(at)washpost.com.

© 2014, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.