We All Live on Turtle Island

When speaking of the natural world, for good reason we often turn to Native American myth. Turtle carries the world on its back is what many of these myths tell us; we are all citizens on turtle island.

Editor’s note: We are pleased to announce a new column, “Letter From the West,” by Deanne Stillman. In this and future installments, Deanne will explore what is going on in our wide open spaces and what we do to each other and all that lives there. As she explains, “Above all else, the personal is geographic and the reverse is true as well. I would like for people to renew our basic connection with the West. Otherwise we are dismantling our country and our heritage all by ourselves.”

Ours is the age of the grand gesture and outrage fatigue; it’s hard to top planes flying into towers, and with every terrible story that has unfolded since 9/11, our attention spans have diminished. Yet now we are awash in images of the Gulf of Mexico in flames and sea creatures swimming in oil gushing from a deep wound in the planet. These images are difficult to look away from, and it seems as if this incident in the Gulf — the blowout deep under the sea that no one had prepared for — is so awful, so final in its consequences that nowadays, for the first time in many years, we are more fully engaged with matters beyond our immediate needs — at least for the moment.

The concern is both general and specific; many people with whom I’ve spoken about the oil spill have been following one very particular aspect of it — the geology of the sea floor or currents in the Gulf. Some are concerned with one animal, either because they always have been or are now drawn to it for a range of reasons. In my case, I find myself preoccupied with turtles. Unable to go down there and wash them, I ponder their fate all the time, dream about them, and was both thrilled and calmed at the news that their eggs are being rescued in a massive operation involving NASA and Federal Express. Because I live in the West and spend a lot of time in the wilderness drylands, my attention has turned to their earthbound kin, the desert tortoise, a prehistoric creature which crosses my path every now and then when I’m hiking in the Mojave.

When speaking of the natural world, for good reason we often turn to Native American myth. Turtle carries the world on its back is what many of these myths tell us; we are all citizens on turtle island. Yet we gringos often overlook our own stories in which various animals have served as totems and avatars (although sometimes that service has not necessarily been intended by the authors). Looking back on my early encounters with turtles, first literary and later real, I realize now that these turtles were among my first guides to the desert, long before I had physically ventured to my spiritual home. As I recall, I met my first turtle in “Eloise,” the classic book about the little girl who lived at the Plaza Hotel with only her nanny, her dog Weenie, and her turtle Skipperdee. “The Plaza is the only hotel that will allow you to have a turtle,” Eloise said in her sophisticated and simple way.

Skipperdee ate raisins and wore sneakers. And he was sensitive; when Eloise went to Moscow, she had to send him back to the Plaza because of a nervous cough. I remember being quite taken with the hotel-bound turtle, perhaps because I, too, was a pampered little girl who lived in luxury until the day that it all ended. When we moved to lesser quarters, my mother bought me a turtle, perhaps as a bridge to paradise lost. But it wasn’t grand hotels that I imagined, nor was it the marble and mahogany of the mansion we had left behind. Instead, the little reptile conjured the natural world, a sanctuary that would never vanish. I don’t think I gave the turtle a name, or if I did, I don’t remember. But it soon became a friend, a slow and steady companion who was always there, in the big glass dish with the plastic palm tree next to my bed. I remember coming home from school and going right to the dish to feed my turtle, fascinated by its slow lumber across the sand and the swirls on its back; somehow it spoke to my deeper streams, and it wasn’t long before I started ordering desert botanicals from Kaktus Jack’s through the mail (although this urge was also fueled by my father’s frequent recitations of his favorite poem, “Eldorado” by Edgar Allan Poe).

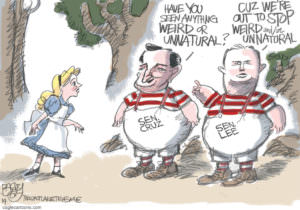

As I now understand it, Skipperdee was preparing me for my next desert ambassador. This was the Mock Turtle in “Alice in Wonderland” — perhaps the most famous turtle in literary history. As many devotees of the Lewis Carroll classic will recall, Alice first learned of the reptile while she was playing croquet with the Queen, who asked if she knew how Mock Turtle soup was made. It was the first Alice had heard of such an animal, and the Queen commanded the Gryphon to take her to the turtle. When they met, he was sobbing, and explained that once upon a time he had gone to school in the sea and learned everything from an old turtle called Tortoise. Alice wondered why he was called Tortoise. “We called him Tortoise because he taught us,” the Mock Turtle explained. Composing himself, he then said that he received a fine education, studying Ambition, Distraction, Uglification and Derision.Alice pondered the information and then the Mock Turtle longingly recalled his earlier life, wiping tears from his eye with his paddle. “You may not have lived much under the sea,” he said, “so you can have no idea what a delightful thing a Lobster Quadrille is.” “What sort of a dance is it?” Alice asked. “Why, you first form into a long line along the seashore,” the Gryphon said. “Two lines!” the Mock Turtle added. “Seals, turtles, salmon, and so on; then you’ve cleared all the jellyfish out of the way. …” “It must be a very pretty dance,” Alice said. “Would you like to see it?” responded the Mock Turtle, happy to demonstrate this part of his past. “Very much indeed!” Alice said, and the Gryphon and Mock Turtle went on to perform the Lobster Quadrille. And then the moment passed but the Gryphon wanted the show to go on. “Would you like the Mock Turtle to sing you a song?” the Gryphon asked Alice. “Oh, a song please, if the Mock Turtle would be so kind,” Alice replied. “Sing her ‘Turtle Soup,’ will you, old fellow?” the Gryphon urged. And once again, the soulful turtle began to sob, belting out the tale of his own demise:

Beautiful Soup, so rich and green, Waiting in a hot tureen! Who for such dainties would not stoop? Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup! Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup! Beau–ootiful Soo–oop! Beau–ootiful Soo–oop! Soo–oop of the e–e–evening, Beautiful, beautiful Soup!

Years later, I was the one who was crying when, during a shamanic journey involving hundreds of people at an airport hotel (click here for full story), I had a vision of my maternal grandmother handing me a vial of tears — my own — as I stood under a Joshua tree in a trance. Along that subterranean path there was a giant desert tortoise; he had accompanied me to the rocky shrine where I received the gift that changed my life, and since then I have been comforted to know that even though I don’t always see them, tortoises are in the Mojave when I am and, more important, when I’m not. Yet I sometimes feel the urge to be near them, and when I do, I drive north from Los Angeles, a latter-day Alice dropping through a freeway sinkhole and emerging at their home in the Desert Tortoise Natural Area near California City.

There’s a famous old tortoise named Mojave Max at Red Rock Canyon in Nevada, and every year school kids bet on the moment when he will crawl out from his burrow after hibernating all winter. In the springtime and into the summer, I like to walk the paths of the Antelope Valley preserve, hoping to get lucky; you can spot a tortoise burrow near the base of the creosote bush, and I sometimes plant myself near one and wait for the ancient critter to reappear. In the meantime, plenty of other desert entertainment abounds. If the rains have come, the preserve is a blaze of glory, with the violet Mojave aster popping on the desert floor, yellow seas of goldfield rippled by the winds, and purple and white profusions of flowers on the calyx bush. Red-tailed hawks and woodpeckers and cactus wrens frequent the tortoise habitat, and of course snakes and lizards and tarantulas also call it home, as do the ground squirrel and badger and coyote.

Once there were vast cities of tortoise in the Colorado and Mojave deserts of California. During the 1920s, there were a thousand of the creatures per square mile. By 1990, the state reptile had become officially endangered. Its habitat was degraded by decades of unchecked cattle grazing, and off-roaders had begun to take their toll. Today there is a profusion of ravens in the desert, because ravens follow what people throw away, and parts of the desert are strewn with leftovers. When they’re finished, they turn to tortoise hatchlings. On the 40 square miles of the sanctuary outside California City, and elsewhere across the Mojave, the desert tortoise is making what may be its last stand. As it happens, this is no ordinary reptile fighting for its life (not that that makes its struggle any less compelling), but a reptile that may actually be like Skipperdee and the Mock Turtle. That is to say, it has a personality, according to a study made several years ago by U.S. Geological Survey biologist Kristin Berry. That critters have certain traits and feelings is not news to me, but if such “news” can stave off extinction, I’m all for it.

Berry studied the tortoise population at the Army base of Fort Irwin, before the animals were relocated to make way for expanded military maneuvers. After outfitting tortoises with transmitters, she learned that No. 43, for instance, a 10-pound alpha male, was actually a bully who turned to mush whenever he looked at a female. “But he was a heck of a fighter,” she told a Los Angeles Times reporter. “And he patrols a huge territory. We’ve seen him make arduous journeys across a wash and halfway up a mountain just to beat up a smaller male.” Then there was No. 41, an old, reclusive female with osteoporosis. She had four boyfriends, preferring them to the alpha males who occasionally visited her. No. 28 was an 80-year-old “cad” and “fearless kingpin.” Soon 300 of the Fort Irwin tortoises would be moved to similar habitat. “There’s so much we don’t know about these creatures,” Berry said.But perhaps we know enough. According to Native American myth, the tortoise is responsible for our very existence. According to Kay Thompson, it kept a little girl company in her big empty suite at the Plaza Hotel. According to the old gringo Lewis Carroll, it remembered how to dance and made sure to pass the knowledge on, before it was made into soup. Recently, I was hiking in a part of the Mojave adjacent to Joshua Tree National Park. It was my father’s birthday. He passed away 14 years ago, and as I walked across the sands on a spring day just after the first wildflowers had shot through, I heard a few lines from “Eldorado” in my head — or maybe it was drifting on the wind — I do not know, but it was my father speaking them: “Gaily bedight, a gallant knight, in sunshine and in shadow, had traveled long, singing a song, in search of Eldorado. …”

I walked on with my little hiking group, and the biologist among us spoke of different kinds of blossoms and how to tell the difference between male and female, and, as we walked, I found myself yearning for the sight of a tortoise. Turning to my right, a large one emerged from its burrow. I was stunned. I had not seen a tortoise in years, and I watched the old fellow paddle across an alluvial fan, making for some greens. In an instant, many things came together. A few years earlier, on the anniversary of my father’s death, in a different part of the Mojave, a coyote appeared, running across some train tracks. My father in fact was a coyote — a trickster — and it seemed right. But a tortoise? At first the idea saddened me; had it come to this — the life of the party now represented by such an ancient, silent and gentle presence? But the more I thought about it, the more I knew the message to be true: His spirit was finally at rest — no more tricks and jokes and now you see me, now you don’t kind of stuff — and he had come to reside in the land of escape that he had conjured for me long ago.

I watched the tortoise clamber on, from flower to flower, its mouth greening up as it devoured the desert buffet. Judging from its size, I guessed that he (or she) was about 75 or 80 years old — my father’s age if he were still alive. It occurred to me that this tortoise could have been the last one in its range, or even the last one in the southern Mojave. Who will teach us the lessons of life and loss and rebirth if it vanishes? I thought as it headed back to its burrow under a creosote bush. Who will teach us the Mojave quadrille?

Deanne Stillman’s latest book is the widely acclaimed “Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West,” a Los Angeles Times “Best Book ’08” and winner of the California Book Award silver medal for nonfiction. Her book includes an account of the 1998 Christmas horse massacre outside Reno, as well as the story of Bugz, the lone survivor of the incident. Follow Deanne Stillman on Facebook.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.