Warren I. Cohen on China’s ‘Factory Girls’

There’s a revolution underway in Chinese culture as young women flock from villages to factory employment in the cities, leaving traditional values behind.

Many years ago, a Fulbright lecturer visited my graduate class at National Taiwan University and asked my students why they studied history. They each responded with variations on the theme that their studies would enable them to serve China. Bemused, the visitor told the class he studied history because he enjoyed it. The response was outrage: my students contended that his motive was frivolous. Maybe “you Americans” could take classes for the fun of it. “We Chinese” would never study anything if it would not help our country.

Leslie Chang’s grandfather came to America in 1920 with precisely the same goal. Contrary to his father’s instructions to seek a degree in literature, inviting his father’s wrath, he chose to become a mining engineer, his perception of what his country needed most.

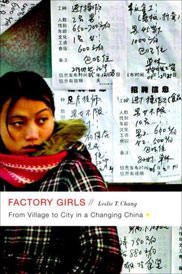

But Chang’s subjects in “Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China” are far less interested in serving China than they are in improving their lives — earning more money, getting bigger apartments — and taller boyfriends. The thread that runs through her account is the revolution occurring in Chinese culture, as young women with money in their pockets reject the values of the village, challenge the authority of their parents and revel in their new freedom.

Chang, a former reporter for The Wall Street Journal, spent several years examining the lives of young Chinese women who migrate from the countryside to Dongguan, a factory town in the Pearl River Delta, not far from Guangzhou and Shenzhen. The factories there produce an extraordinary range of goods, primarily for export. Seven million or more migrant workers turn out plastic parts for most everything, toys for Hasbro and Mattel, luxury handbags for Coach, and an enormous percentage of the world’s athletic shoes. Most of the latter are manufactured by Yue Yuen, a Taiwanese-owned plant that employs 70,000 workers and contains its own kindergarten, hospital, and fire department, as well as its own criminal gangs. Dongguan also appears to be a center for prostitution, with some of the brothels disguised as karaoke bars where attractive and better-educated women find the work more appealing than joining an assembly line.

Working conditions in the factories are generally brutal, comparable to the worst found in the West in the 19th century. Yue Yuen is noted for paying its workers on time, despite the poor reputation of Taiwanese-run businesses. Many of the firms consistently cheat the workers out of their salaries and they have little if any legal recourse. To the extent that local officials get involved, it is to collude with the factory owners and managers. Seeking payoffs, not justice, is their purpose. Chang observes tartly that in Dongguan, government service is an alternative route to profiting from the market economy. The workers join the culture of corruption by lying about their job qualifications, stealing merchandise and taking kick-backs if they are able to move up to more responsible positions. It’s a Chinese variation of the old Soviet adage: “You pretend to pay us and we pretend to work.”

“Factory Girls” contains two interwoven tales. The primary story is of the women of Dongguan, two in particular — the conditions in which they live and work, their aspirations, how they are changed by their experiences, and what these changes mean for China. Scattered through the narrative is the story of Chang’s own family, the Zhangs of Manchuria.

Born in the United States, majoring in college in American studies, deciding to begin her career in Prague, Chang was determined not to seek her roots in China. For 12 years after she began working there, she chose not to look for relatives or to visit her ancestral village. Eventually, perceiving that the grandfather who studied in the United States, became a Chinese government official, and was murdered by the Communists in January 1946, was also a migrant of sorts, she tried to piece together the modern history of the Zhangs. It’s a familiar story of the suffering of those who stayed to build the “New China” — and endured the torments of Mao’s utopian vision — contrasted with the successes of those who migrated, first to Taiwan and then on to the United States. Interesting, sad, but ultimately not as compelling as the story of her factory girls.

One of two women upon whom Chang focuses is “Min,” who is constantly jumping from one factory job to another in an effort to improve her working conditions and salary. Dongguan has a talent market where Min and others attempt to sell themselves to prospective employers, never scrupling to lie about their experience or qualifications. Forged diplomas are readily available, but degrees are of little importance in the factories, as long as one can do the work required.

On one occasion, Chang travels with Min back to her home for the Lunar New Year. Min’s family home is primitive, without plumbing or much space. The women sleep together in one bed, head-to-toe. Min’s parents — and apparently the parents of most factory girls — seem to ask two things of their daughters. They want them to marry local husbands, from the same province at minimum, preferably from the same county. And they want money. Chang contends that parents see migrant workers as cash machines. But Min and her older sister see no reason to be responsive to parental pressures. Angering her mother, her older sister goes off with a man from a different province. When Min’s father complains that other girls send home more money, her retort is that other fathers go to work to earn what they need. This is not the traditional Chinese village that we all studied back in the last century. Chang’s other principal subject is Chunming, older than Min, and intent upon self-improvement, as are many of the factory girls. In what little time they have after work, many take English classes, usually taught by charlatans. Others attend lectures by motivational speakers who tell them how to become rich by direct sales of items such as cosmetics, Tibetan medicines or “soul pagodas” — spaces where a loved one’s ashes can be deposited after cremation. Some of these turn out to be pyramid schemes.

Chunming, who had several striking successes in sales and a precipitous fall as an entrepreneur during the period Chang followed her, was constantly reading self-help books in search of guidance. At one point she was focused on Benjamin Franklin’s 13 virtues. Another woman confided to Chang that she was seeking wisdom from “The Bible of Jewish Home-Schooling” to learn how to do business according to the Talmud.

One of Chang’s most fascinating observations has to do with the importance of the mobile phone to her factory girls. It is the only means of contact for what is essentially a floating population. Most of the women live in dormitories, but move from one to another as they change jobs. They can find each other again — and their boyfriends — by calling them on their mobile phones. At one point, Min’s phone was stolen and with it all the contact information she had for everyone she had met in Dongguan. She had little choice but to begin her social life all over again.

Another point Chang notes is the sexual freedom her young women enjoyed. The Internet seemed to be the favorite vehicle for arranging dates, with both parties usually lying about vital statistics — and the men often about marital status. Sometimes they posted doctored photos. None of this would be unusual in the United States or Europe, but sleeping with multiple partners was not something life in the village had allowed. Dongguan permitted its residents a degree of privacy, at least for those who had succeeded in leaving the dormitories for their own apartments, however grim these may have been.

Finally there is the absence of Mao. It’s not likely that many factory girls turn to Ben Franklin for guidance, but there’s no indication that any of them are carrying around Mao’s “Little Red Book.” Communism as ideology is absent from Dongguan, from its museum and from its conversation. Indeed, the young women demonstrate remarkable political ignorance and indifference, often unaware of who China’s current leaders are — and not caring.

Chang’s subtitle conveys the meaning of her story. The migrants, more than 100 million nationwide, are changing China. Unmoored by their travels from the village to the city, they leave traditional values behind. Returning to their homes for the Lunar New Year, they find village life stifling and their behavior and rhetoric leaves their families discomforted and unsettled.

Much of this experience will be familiar to students of urbanization all over the world: “You can’t go home again.” What remains to be seen is what impact the current recession, with tens of thousands of Pearl River Delta workers being laid off, will have on the structure of Chinese society. The factory girls of Dongguan, unlike previous generations of Chinese women, seem most unlikely to just sit around and chi ku (eat bitterness).

Warren I. Cohen, professor emeritus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and senior scholar in the Asia program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, is the author of several books, including “America’s Response to China,” the fifth edition of which will be published by Columbia University Press next year.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.