Warren I. Cohen on China’s Charm Offensive

The Beijing Olympics are proof that the rule of China's Communist Party has been validated. Yet human rights abuses continue. What's really going on? What kind of country is China becoming? Two new books help provide answers.

The Olympics have gone to China, exposing the many contradictions within Chinese society and among international perceptions of the modern Chinese state. Newspapers and periodicals are filled with stories and photos of the magnificent new world-class architecture in Beijing and Shanghai. President George W. Bush and other world leaders attended the opening ceremonies. This is a moment of enormous pride for the Chinese people. Hundreds of thousands celebrated in Tiananmen Square in the summer of 2001 when the announcement came that Beijing had been awarded the 2008 games. The age of humiliation was over. China’s resurrection as a Great Power has been recognized and the past sins of the Beijing regime have been forgotten, at home and abroad. China’s status in the world has not been so high since the days of the Qianlong Emperor, back in the 18th century. The rule of the Chinese Communist Party has been validated.

Charm Offensive

By Joshua Kurlantzick

Yale University Press, 320 pages

Out of Mao’s Shadow

By Philip P. Pan

Simon & Schuster, 368 pages

But reports of the harassment, detention and arrest of dissidents all over China, apparently aimed at preventing unpleasant scenes that might detract from the glory of the games, are also filling the media. Contrary to promises made to the Olympic Committee, the Chinese government does not appear to be making a serious effort to demonstrate its respect for human rights. The recent abuses provide additional evidence of continuing repression in China. What’s going on? What kind of country is China becoming?

For my generation of students of modern China, the defining moment came on June 4, 1989, when the People’s Liberation Army massacred hundreds of the people in the vicinity of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Conceivably thousands more were killed elsewhere across the country — all for the crime of protesting against their government’s arbitrary use and abuse of power. For me, that stain will remain at least until the Chinese government admits what it did and apologizes to the families of the victims and to the citizens of China. I don’t expect to live to see that day. And most of my Chinese friends, including some who participated in the protest movement, tell me that it’s time to move on — as they have. I’ve discovered that many, probably most, Chinese college students are unaware of what happened in 1989, that the government has suppressed that memory, as it has memories of many of the horrors that the Chinese Communist Party has inflicted on the Chinese people.

Two new books — Philip Pan’s “Out of Mao’s Shadow” and Joshua Kurlantzick’s “Charm Offensive” — look at today’s China from very different perspectives. They describe the conflicting forces within China and the difficulty the international community has in understanding what’s happening there. Pan, one-time Washington Post bureau chief in Beijing, roamed the country collecting tales that provide evidence of the Communist Party’s transgressions, past and present, of its increasing corruption, and of its determination to retain a monopoly on political power. Crushing those who attempt to keep alive memories of the sins of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping or who try to reveal or seek restitution for the crimes of the thousands of avaricious officials who plague the nation today, the one-party state rolls on. The scores of thousands of mass demonstrations annually against its practices change little. And, he argues, the party has succeeded in part because the people have been willing accomplices in the act of forgetting. Movingly, depressingly, Pan tells the story of some of the ordinary people and some of the rights activists, lawyers and journalists who struggle, largely in vain, to call the party to account.

On the other hand, Kurlantzick, also a journalist, focuses on China’s international achievements, its growing influence in Asia and the world. Lamenting the sullying of America’s image in the world, he conjures up a China overtaking the United States in the affections of mankind. He is not unaware of Beijing’s miserable human rights performance or of the Communist Party’s arbitrary and unchecked rule. He notes, however, the success of Chinese leaders in keeping the outside world focused on their nation’s economic miracle — the extraordinary development of its coastal economy over the last 10 to 15 years and the millions of its people it has lifted from poverty. He attributes China’s growing influence in the world to its “soft power,” a term deriving from the work of Harvard professor Joseph Nye, who was an assistant secretary of defense in the Clinton administration. Nye defined soft power as a brand, a view, for example, of the United States as a beacon of values universally treasured, excluding any form of coercive power. Kurlantzick stretches the term a bit to include the Chinese government’s use of its increasing wealth to buy friends, either by investing in the development of some countries and threatening, however implicitly, to withhold investment from others.

There is no denying that today’s Chinese diplomats are well trained and effective representatives of the regime. Nor can it be denied that for the last decade, China’s approach to the outside world has been less abrasive and that it has moved haltingly and grudgingly toward acceptance of international norms of behavior — toward becoming a “responsible stakeholder” in the international system. Not least, Beijing has played the critical role in keeping Kim Jong Il’s minions at the negotiating table, keeping alive the hope that North Korea’s nuclear weapons will be destroyed some day. In general, as the United States seems content to abdicate its role as the dominant power in East Asia, there can be no doubt that China is poised to fill the gap.

Pan is less interested in China’s international role. He examines China’s evolution since the death of Mao from the bottom up, from the perspective of those being screwed by the system. In the 1950s and again in the 1980s, the great investigative reporter Liu Binyan bravely exposed the corruption of provincial officials and the helplessness of their victims. Twice he was expelled from the party, suffering 21 years of forced labor the first time and exile the second. Today, other brave young reporters appeal to the Chinese constitution, to the laws that allegedly govern party officials as well as ordinary citizens, but their exposés are more likely to end with them in prison than the culprits they indict. Lawyers and rights activists are barred from court, harassed, beaten or put under house arrest. When there are trials, the courts are almost always controlled by the party officials responsible for the behavior being challenged. The party is above the law. Zhao Ziyang was general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party during the Tiananmen demonstrations in the spring of 1989. Pan begins with the story of Zhao being pushed aside for his unwillingness to crack down on the demonstrators and then spending the rest of his life under house arrest — punishment admittedly far more benign than anything Mao would have meted out. Zhao’s continued refusal to accept the party line — that the students camped in the square were counterrevolutionaries who needed to be bloodied — resulted in his becoming a nonperson. As far as the official media were concerned, he ceased to exist. In standard Leninist fashion, his past performance, as reformist premier as well as general secretary, was deleted from the public record. And then, in 2005, he died — and the party leaders, fearing a revival of the debate over its actions in 1989, panicked. They did not want to risk a funeral becoming a popular celebration of Zhao, to the detriment of the party’s reputation. But efforts to keep his death secret and to limit the number of people who could attend memorial services failed. Thousands went to pay their respects, braving police harassment — and it is with those thousands that Pan places what little hope there is for the democratization of China in the foreseeable future.

Pan’s subsequent chapters focus on a number of courageous individuals who refuse to be cowed by the authorities. An amateur documentary filmmaker obsessed with telling the story of a young woman, a devout communist, put to death in 1968 for refusing to repudiate her earlier criticism of Mao’s policies, for refusing to accept the “Rightist” label, receives the most attention. Pan also writes of victims of the Cultural Revolution and people who struggle to keep their memory alive, of factory workers who tried to organize to fight for wages and pensions stolen by officials, of a journalist and a free-speech advocate who challenged the party, and of the doctor who bravely revealed the true story of the SARS epidemic in Beijing in 2003 — and then dared to exploit his celebrity status to demand that the party tell the truth about what happened at Tiananmen in 1989. One of Pan’s most interesting chapters, titled “The Rich Lady,” is the story of a less admirable character, a woman from modest circumstances who suffered during the Cultural Revolution and then shrewdly developed connections with party officials. Those relationships enabled her to become one of the wealthiest people in China, with a fortune estimated at $550 million. She and others like her are quite content with party rule: Democracy is not in their interest.

Pan demonstrates again and again that China is run by a Leninist party that remains above the law, that denies its people freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from fear. The Chinese Communist Party has co-opted entrepreneurs and many, perhaps most, intellectuals. Many of those who rode bicycles to work and lived in dank apartments in the 1980s now live in attractive detached houses in the suburbs — and have lost the urge to demonstrate against the government. Coal mine operators collude with officials to ignore safety requirements and thousands of Chinese miners die in accidents every year. Pan estimates that one Chinese miner dies every 30 minutes. Developers like “The Rich Lady” bribe party officials who allow them to drive people off their land and out of their homes to make way for high-rises and shopping malls. Pharmaceutical companies adulterate the drugs they sell while complicit bureaucrats look the other way. And the hundreds of millions who still lead marginal lives at best have been manipulated by clever appeals to nationalism, such as surround the Beijing Olympics, and are persuaded that in a great China a better life will one day trickle down to them or their descendents. The Chinese government, Pan suggests, is conducting what may be the largest and most successful experiment in authoritarian rule. He came across a handful of decent men and women who still fight for democracy and the rule of law, for respect for human rights in China, but he found little cause for optimism.

Kurlantzick, however, demonstrates why Chinese leaders are themselves optimistic about their nation’s future. He sees a nation that through its “charm offensive” is succeeding in changing perceptions of itself from threatening to benign. China’s revolutionary days are over: Communism as Lenin or Mao might have understood it is gone. China is now a capitalist dynamo, driving the world economy. Its regime provides a model for undemocratic governments throughout the world: Authoritarianism works. It can bring prosperity to the people, legitimacy and staying power for the rulers.

Moreover, Kurlantzick reminds us frequently that the American brand has been tainted by the failure of Americans to live by their principles. Once the world viewed Americans as liberators and thrilled to hear that “the Yanks are coming.” But the Yanks never appeared in Rwanda, and their invasion of Iraq is widely perceived as wrongheaded. How can the United States claim the moral high ground in the face of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, after its leaders approved the methods of torture used by the Chinese Communists against American POWs during the Korean War? How can Americans talk of democracy and fair elections after the travesty of the vote count in Florida in 2000? Once emigration to the United States was the dream of the poor and the oppressed all over the world. Since Sept. 11, 2001, its doors have been all but slammed shut in the faces of foreign students and workers. International polls in recent years justify Kurlantzick’s concern: More people fear the United States than fear China; increasingly, China is a nation to be admired. Its support for the Sudanese government despite that regime’s genocidal policies in Darfur, its support of Mugabe in Zimbabwe and of the murderous Burmese junta appear to offend fewer people than does the hypocrisy of the American government.

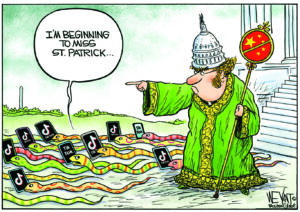

For the United States, the dilemma is obvious. The People’s Republic of China is a power with which it must work. China is too big and too strong to ignore or to intimidate. Beijing is beginning to compete successfully with Washington in efforts to shape the international system while its leaders simultaneously deny their own people basic human rights and refuse to be bound by their own constitution and laws. Sadly, there is no choice for Americans. As the power and influence of their nation have drained away in recent years, they are offered no alternative to “engagement,” to attempting to work constructively with a regime whose leaders do not share their values. Thus far there has been little talk of policy toward China in the U.S. presidential election campaign, and China’s leaders are smugly complacent about the outcome. They are confident that no American president will pose an obstacle to China’s “peaceful rise,” to the success of its “charm offensive.”

Warren I. Cohen, professor emeritus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and senior scholar in the Asia program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, is the author of several books, including “America’s Response to China,” the fifth edition of which will be published by Columbia University Press next year.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.