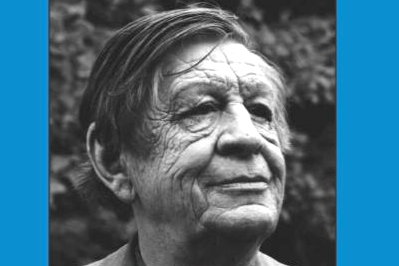

W.H. Auden, Complete

These six volumes of the work of W.H. Auden call to mind the great poet's comment on the writing of another author: "It is a book in which one can browse for a lifetime without exhausting its treasures." Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press

“The Complete Works of W.H. Auden: Prose: Volumes V and VI” A book edited by Edward Mendelson

Where should the praise go for this magnificent edition of W.H. Auden’s prose, now rounded off by its final two volumes? To the great Anglo American poet himself for having produced such incisive and memorable criticism? To Edward Mendelson, whose scrupulous editing calls to mind Samuel Beckett’s phrase “No author better served”? Or to designer Jan Lilly and the Princeton University Press for the elegance and beauty of the books themselves? One thing is certain: This is what scholarly publishing is meant to be.

Which isn’t to say that this set will appeal only to an academic audience. These hefty volumes incorporate — along with much, much else — all of Auden’s previously published collections of lectures and literary journalism. Volume III showcases “The Enchafed Flood,” a study of “the romantic iconography of the sea” (and one of my favorite books). Volume IV includes “The Dyer’s Hand,” which assembles many of Auden’s greatest essays. Volume V contains “Secondary Worlds,” talks on religion, drama, the Icelandic sagas and opera, and Volume VI reprints the full text of “A Certain World,” a scrapbook of quotations from the poet’s reading, enhanced by his own commentary. Scattered throughout the sextet are the pieces selected by Auden, with Mendelson’s assistance, for what became the posthumous 1973 collection, “Forewords and Afterwords.”

In short, here is God’s plenty, 4,000 pages in which to lose oneself as one does in, say, Boswell’s “Life of Johnson” or Henry Mayhew’s “London Labour and the London Poor.” Auden’s judgment of the latter — a classic of 19th-century reporting and oral history — could be readily applied to his own collected prose: “It is a book in which one can browse for a lifetime without exhausting its treasures.” When Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky called Auden “the greatest mind of the 20th century,” he may have exaggerated — but not by much.

Published in tandem, the last two volumes of the collected prose cover the final decade of Auden’s life (he died at 66 from a heart attack). In his introduction to Volume V, Mendelson aptly sums them up:

“Auden’s essays and reviews in the last dozen years of his life are most vivid and memorable when he writes explicitly about others’ lives or elliptically about his own. He was especially fascinated by artists and writers who were more or less monstrous or obsessive, who exemplified intellectual temptations that he himself had experienced and refused (Goethe, Kierkegaard, Wagner). He enjoyed writing about the saintly (Henry Mayhew, Dorothy Day), the aesthetic (Oscar Wilde, A.E. Housman, Max Beerbohm), and the sexually eccentric (J.R. Ackerley, Denys Munby). He wrote enthusiastically about the byways of Christian theology and classical myth.”

Auden’s journalism and criticism, like his stints as a lecturer and teacher, were mainly undertaken to pay the bills, but he never became a hack. When in 1966 Life magazine offered the enormous sum of $10,000 for 6,000 words on the fall of Rome, he turned in a heavily researched piece that compared the 3rd century with the 20th and duly predicted that our world would soon go smash. When the editors balked and asked for a rewrite, Auden stood his ground. As Mendelson notes, “The essay was rejected and he was paid nothing.” On another occasion, when an anthologist asked to reprint some early poems, including the famous “Spain” and “September 1, 1939,” Auden agreed but insisted on this printed stipulation: “Mr. W.H. Auden considers these five poems to be trash which he is ashamed to have written.”

Over the years I’ve collected Auden’s books — both his own and the works he edited — and so I feel reasonably familiar with his writing. But there’s much here I’d never seen before. At the same time, these pages refresh our appreciation of, say, the poet’s introduction to Anne Fremantle’s “The Protestant Mystics” or to his own selection of Dryden’s verse by showing them as products of a busy professional life. Moreover, Mendelson’s notes and appendices contribute illuminating, and sometimes amusing, extra-textual detail. For instance, Auden reviewed with kindness the rather tepid memoirs of the famous Oxford don Maurice Bowra. In an endnote, Mendelson states, without comment, that “In describing Bowra as ‘one of the most decent of men,’ Auden knew perfectly well that Bowra detested him and had widely denounced his poetry and character.”

Among the treasures of Volume V is the full text of Auden’s lecture “Culture and Leisure,” delivered in 1966 at Catholic University. With notable prescience, the poet zeroes in on one effect of modern technology on art and literature:

“This ease of access is in itself a blessing, but its misuse can make it a curse. We are all of us tempted to read more poetry and fiction, look at more pictures, listen to more music than we can possibly respond to properly, and the consequence of such over-indulgence is not a cultured mind but a consuming one; what it reads, looks at, listens to, is immediately forgotten, leaving no more traces than yesterday’s newspaper.”

Perhaps Auden’s only fault as an essayist is an occasional tendency to adopt a slightly dogmatic, schoolmasterly tone. Moreover, his orderly mind gravitates, perhaps inordinately, to diagrams, lists and charts, while his discussions of theology and philosophy demand patient attention. But everything he says about poetry is sharp and authoritative: “In judging a poem, one looks for two things: craftsmanship — it should be a well-made verbal object; and uniqueness of perspective — nobody but the author could have written it.”

Despite the overall excellence of this edition, there are occasional blemishes. For example, the index gives the wrong page number for the introduction to M.F.K. Fisher’s “The Art of Eating” (it’s on Page 37, not 27); it was Robert Phillips, not my mentor Robert Phelps, who edited “Aspects of Alice”; and a phrase from one of Hitler’s speeches is mistranscribed, the German word “mit” having become “wit.” Such errors, although annoying, are forgivable, given the overall grandeur of the project.

After all, “A Certain World” alone takes up nearly half of Volume VI, and it is a grab-bag of humor, aphorism and moral reflection. Under “Prayers, Petitionary,” Auden includes a line from the camp novelist Ronald Firbank that should be embroidered on a sampler: “ ‘Heaven help me,’ she prayed, ‘to be decorative and to do right.’ ” Under “Book Reviews, Imaginary,” he preserves several gems by the humorist J.B. Morton. Speaking of “Fain Had I Loved,” by Freda Trowte, Morton writes, “There is an indescribable quality of something evocative yet elusively incomprehensible about her work. The character of Nydda is burningly etched by as corrosive a pen as is now being wielded anywhere.” Another review, of “Brittle Galaxy,” by Barbara Snorte, ends quite simply: “1,578 pages of undiluted enthrallment.”

Oddly enough, that’s basically what all authors want said about their books. However, in the case of Auden’s collected prose, “undiluted enthrallment” seems very close to the truth.

Michael Dirda is a regular book reviewer for The Washington Post’s Style and the author of the just-published “Browsings: A Year of Reading, Collecting, and Living with Books.”

©2015, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.