Unsurprising Affirmative Action Decision Is Bad News for Gay Marriage

The current Supreme Court has consistently decided for states' rights and majority rule, which could be a problem as same-sex marriage cases work their way through the judiciary. A supporter of gay marriage waves his flag during a rally at the Utah State Capitol. More than 1,000 gay couples rushed to get married when a federal judge overturned Utah's constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage in late December 2013. In early January the U.S. Supreme Court granted Utah's request for an emergency halt to the weddings. AP/Rick Bowmer

A supporter of gay marriage waves his flag during a rally at the Utah State Capitol. More than 1,000 gay couples rushed to get married when a federal judge overturned Utah's constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage in late December 2013. In early January the U.S. Supreme Court granted Utah's request for an emergency halt to the weddings. AP/Rick Bowmer

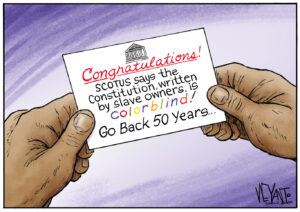

The most difficult thing about predicting the outcome in the case of Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action was never whether the Supreme Court would uphold a Michigan ballot initiative banning racial preferences in college admissions, or by implication also endorse similar laws that have been enacted in seven other states. To paraphrase the late great Los Angeles Lakers play-by-play announcer Chick Hearn, you could have “called that one with Braille.”

Even in its long-ago liberal days, the Supreme Court took an ambivalent position on race-based affirmative action. The greater uncertainties in Schuette were always whether the high court, in addition to approving the Michigan measure, would once again embrace the fiction that racial discrimination is a thing of the past, and whether the court would endorse a concept of majority rule or popular sovereignty that could have ripple effects for other constitutional issues, specifically those implicated in statewide bans on same-sex marriage.

Although the court’s 6-2 decision actually consists of five separate opinions — a plurality decision authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy, separate concurrences by Chief Justice John Roberts, Justices Antonin Scalia and Stephen Breyer, and a lengthy dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, which was joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg — the uncertainties to a significant extent have been resolved, and for the worse. A working majority of the court believes that we live in a post-racial world and that in all but the rarest of circumstances, popular majorities should have the last word on defining the constitutional rights of minorities.

True to the fantasy of ethnic harmony, Kennedy’s opinion refers to contemporary America as a society in which the lines of racial division “are becoming more blurred” and efforts to advance the interests of “certain groups” as opposed to others lack “clear legal standards or accepted sources to guide judicial discretion.” The better course on affirmative action, accordingly, is simply to let the voters of each state decide whether to permit the practice or abolish it. In any event, Kennedy concludes, “[t]here is no authority in the Constitution or in this Court’s precedents” to do otherwise.

Although Kennedy did not cite Shelby v. Holder, last year’s historic decision that gutted the Voting Rights Act, his reasoning was strikingly reminiscent of Roberts’ majority opinion in Shelby, which also took the view that racism is a remnant of the past. Joined by Kennedy, Scalia and Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, Roberts concocted a novel constitutional doctrine in Shelby — the principle of “equal sovereignty” among the states — to justify the court’s holding that states and localities with histories of racial discrimination in elections could no longer be held to higher levels of legal scrutiny and review than those without such histories.

Sotomayor, by contrast, cited Shelby four times in her impassioned dissenting opinion in Schuette. Emphasizing repeatedly that “race matters,” she castigated the majority for turning its back not only on the Constitution, but on reality itself. Race matters, she wrote, not only because of the nation’s history of denying minorities “access to the political process,” but because of “persistent [present] racial inequality in society — inequality that has produced stark socioeconomic disparities.”

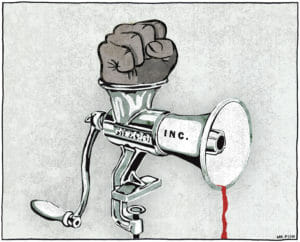

We can see in Shelby and Schuette how the court’s concept of popular sovereignty was utilized to distort reality and undermine voting rights and affirmative action. The big unanswered question now is whether that concept will carry the day if and when the issue of same-sex marriage returns to the court.

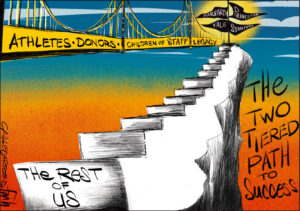

Although a growing number of lower courts have invalidated gay marriage bans and recognized the constitutional right of same-sex couples to wed, the Supreme Court has yet to rule on the core constitutional question. Indeed, in its two landmark gay marriage rulings last term — Windsor v. United States and Hollingsworth v. Perry — the court skirted the issue.

In Hollingsworth, the majority dismissed on highly technical federal “standing” grounds the appeal that had been brought by the proponents of California’s Proposition 8, the ballot initiative that voters passed in the 2008 election outlawing gay marriage. In Windsor, the court struck down section three of the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as the union of one man and one woman for purposes of federal laws and benefit programs.

But threaded within the majority opinion in Windsor — which was written by none other than Kennedy — was, as I have previously noted on Truthdig, a narrative of states’ rights and popular sovereignty, whereby he and the majority recognized that with few constitutional exceptions (pertaining, for example, to now-defunct state laws prohibiting interracial unions), the definition of marriage traditionally is left to the states and their electorates. The Windsor ruling did not alter that tradition. To the contrary, Kennedy’s Windsor opinion ended with the stark admonition that “its holding [was] confined to those lawful marriages” in states that have opted to recognize same-sex unions.

So will the notion of states’ rights, popular sovereignty and majority rule rippling through Shelby, Windsor and now Schuette ripple further and deal the marriage equality movement a crippling setback? We can be certain only that the legal groundwork has been laid.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.