Unraveling the Enigma of Schizophrenia

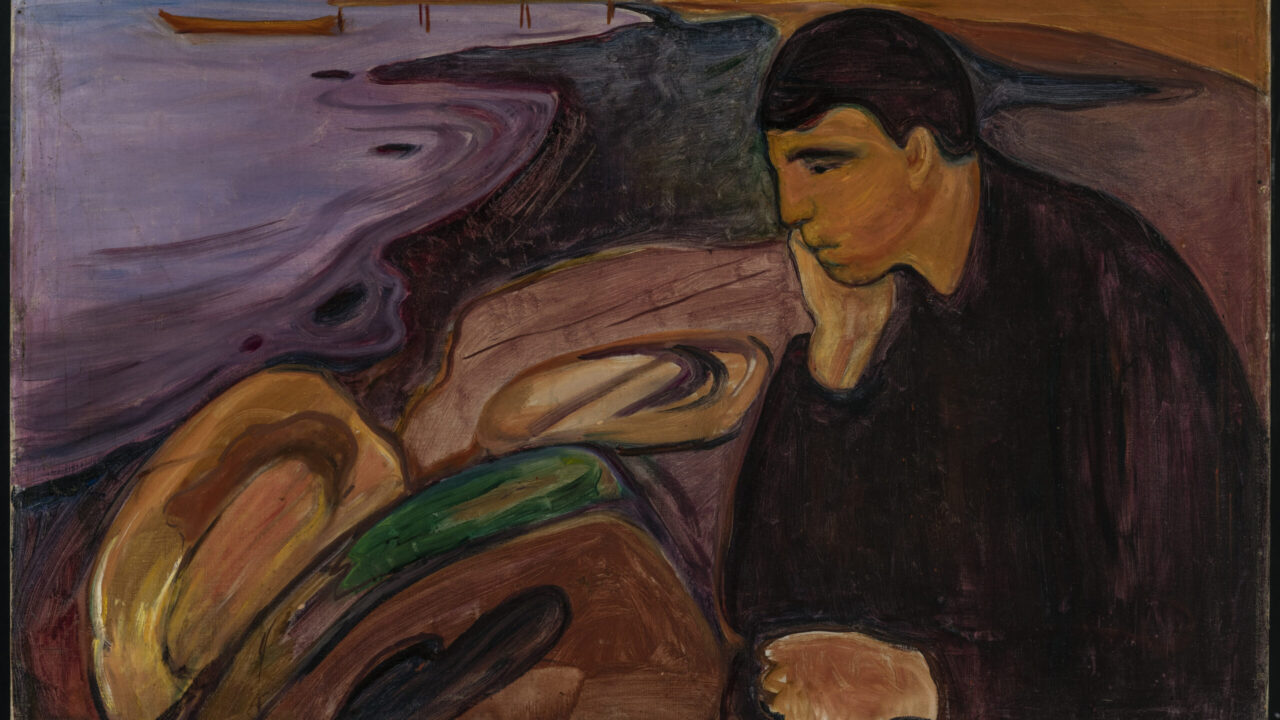

A new book argues that we are finally making progress in understanding the elusive mental health disease. Edvard Munch, "Melancholy" (1894). Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Edvard Munch, "Melancholy" (1894). Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Schizophrenia has long been understood to be among the most serious and intractable of all mental disorders. The condition typically begins in early adulthood and lasts a lifetime. Its hallmark features include hallucinations, withdrawal from social situations, and serious problems in cognition, such as a highly irrational belief system and a limited attention span.

In “Malady of the Mind: Schizophrenia and the Path to Prevention,” a comprehensive history of this perplexing mental disorder from the Ancient World to the present, Jeffrey A. Lieberman argues that psychiatry has finally turned a corner in determining both what causes schizophrenia and how to treat it. “Due to the progress and success of science,” he concludes, schizophrenia is “a malady of the mind no more.”

It’s a bold pronouncement to make, given that Lieberman himself admits that the history of psychiatry is filled with declarations of victory over a disorder that nonetheless continues to defy efforts to pin it down. Several once-heralded treatment—say, insulin coma therapy and ice-pick lobotomies, which were both popular in the 1940s—are now dismissed as barbaric. Likewise, while antipsychotic medications, which were introduced with great fanfare in the mid-1950s and remain today’s treatment of choice, can reduce the intensity of the most troubling symptoms for some patients, they are far from a cure. The chapters on past approaches are elegantly written and are helpful in giving context to current debates about how best to address this devastating illness.

Lieberman’s current optimism, however, is rooted in the findings of biological psychiatrists over the last forty years. A longtime professor of psychiatry at Columbia—he was department chair until a year ago when he was suspended after posting a tweet that was widely considered racist and misogynistic— Lieberman himself has been a central figure in this research, having co-authored hundreds of studies in the nation’s most prestigious medical and psychiatric journals and written or edited 10 books on mental illness. Lieberman, who served as president of the American Psychiatric Association a decade ago, has also won several prestigious awards for his scholarly oeuvre, including the Lieber Prize for Schizophrenia Research from the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders and the Neuroscience Award from the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Lieberman’s repeated assertion that schizophrenia is largely a genetic or inherited disease is shaky at best.

As he sees it, biological psychiatry has made major advances that have put our understanding of schizophrenia on firmer scientific footing than ever before. He argues, for example, that modern research supports the notion that genetic factors play a dominant role in the onset of schizophrenia. We now know, he writes, “the numerous means by which genes conspire to preserve and confer schizophrenia.” He also suggests that numerous studies of drugs such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, and stimulants show that the dysregulation of certain neurotransmitters—say, dopamine—are primarily responsible for causing the disorder. For Lieberman, schizophrenia is a brain disease that typically responds well to current medical treatments.

The problem is that Lieberman’s framing of schizophrenia as a disorder that science is finally on the precipice of conquering runs counter to the views of many leading experts in his own field—including two former directors of the National Institute of Mental Health, Steven Hyman and Thomas Insel—who maintain that the so-called biological revolution in psychiatry has failed to deliver on its promise to unravel the mystery of complicated disorders like schizophrenia. As Lieberman himself notes, Insel, the author of “Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health,” has stated publicly that recent neuroscience research has produced no scientific breakthroughs, nor has it done much to improve patient outcomes. (In his book, Lieberman describes Insel’s comments as “unsettling.”)

Similarly, Lieberman’s repeated assertion that schizophrenia is largely a genetic or inherited disease is shaky at best. As sociologist Andrew Scull stresses in “Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness,” psychiatrists have been making this claim for over a century, and it has often relied on little more than fuzzy correlations such as the observation that the illness tends to run in families.

Lieberman does concede that the search for a single gene responsible for the disorder, which lasted several decades and gobbled up billions of research dollars, ended up going nowhere and has recently been jettisoned. As he argues, psychiatrists couldn’t find a single gene because “many genes, possibly one hundred to two hundred, combine to confer disease vulnerability.” But as Scull notes, these genome-wide association studies are also not proving particularly helpful in pinning down the underlying biology of mental disorders. “This huge array of factors accounts for a small fraction of the risk for schizophrenia,” Scull writes.

A firm believer in the “wonders of psychopharmacology,” Lieberman contends that the lifelong use of antipsychotic medication—often in combination with other psychoactive agents—is essential to treatment. But while antipsychotics — there are now about 30 options — can often be helpful, for about 30 percent of patients they are not effective at all, as the scientific literature of the last quarter century demonstrates. What’s more, a host of noxious side effects are common even among those for whom these medications are helpful, including excessive weight gain, extreme lethargy, and tardive dyskinesia —a neurological disease consisting of involuntary movements of the lips and tongue, among other muscles.

As a result, an overwhelming majority of patients—about 75 percent, according to a definitive 2005 study in The New England Journal of Medicine co-authored by Lieberman himself—end up discontinuing their antipsychotic medication within a year and a half. These problems with antipsychotic drugs, which Lieberman seems to downplay, are a key reason why Anne Harrington, a historian of science at Harvard, concludes in “The Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness” that psychiatry has “overreached, overpromised, overdiagnosed, overmedicated, and compromised its principles.”

Schizophrenia affects less than 1 percent of the population—around 1.5 million Americans—many of whom are in prison or live on the streets. According to Lieberman, these patients urgently need not only medication but psychosocial therapy, a safe living arrangement in the community, and the reliable and significant support of a family member or health care provider. Perhaps the most moving sections of Lieberman’s book cover a few innovative programs consisting of intensive support services that have enabled many patients to carve out meaningful lives. One of the programs he highlights, OnTrackNY, is a state-funded treatment program for young people who have experienced their first bout of schizophrenia.

Each patient in the OnTrackNY program works with a support team, which includes a psychiatrist, a primary care doctor, a nurse, and a few other health care professionals. The team adheres to a shared decision-making model about all aspects of treatment, including the use of medication, which some patients decide not to take.

The OnTrack program, which expanded nationwide, has significantly reduced hospitalization rates, from 70 percent to 10 percent, and doubled employment and education enrollment rates. And according to Ilana Nossel, a psychiatrist and co-director of OnTrackNY, it’s the attentive care—rather than the medication — that seems to make the biggest difference. As Nossel explains to Lieberman in the book, the program aims to help patients with “concern, welcome, [and] warmth.”

“The real emphasis,” she adds, “is on relationships.”

It’s commendable that Lieberman includes anecdotes like these—a clear nod to the importance of a holistic approach to treatment. But the very success of these programs also seems to undercut many of the broader arguments made in Lieberman’s book—principally the notion that medication should be viewed as the central pillar of treatment.

Lieberman is on very solid ground when he asserts that the nation’s health care system is holding back further progress.

Indeed, Lieberman laments that most pharmaceutical companies have recently reduced or eliminated their development programs for schizophrenia drugs. But this is not, as Lieberman suggests, because these for-profit companies have suddenly become reluctant to fund effective treatments; it’s because they realize that the promise of a magic bullet that will cure schizophrenia, which biological psychiatry has been promising for some 70 years, has never materialized. As the former head of neuroscience at Eli Lilly and Amgen wrote in the Schizophrenia Bulletin in 2012 regarding the lack of any truly novel psychiatric drug in decades: “Psychopharmacology is in crisis. The data are in, and it is clear that a massive experiment has failed.”

More than a decade has passed since that grim assessment, and a truly effective new drug treatment —one that can control symptoms for most patients without freighting them with miserable and sometimes incapacitating side-effects—remains elusive. Given this, Lieberman’s central conclusion in “Malady of the Mind”—that schizophrenia could be as successfully treated as Covid-19 if only the federal government would properly invest in novel drug development—seems to ignore the epistemological crisis that many practitioners say still dogs psychiatric medicine today.

Lieberman is right to insist that patients diagnosed with schizophrenia have been stigmatized as hopeless cases, and that they would invariably fare much better if the nation devoted more financial resources to their care. But the book’s overarching theme of scientific achievement in diagnosing and treating schizophrenia, as well as its characterization of what modern care ought to entail, never seem to satisfactorily grapple with the failures of biological psychiatry writ large, nor fully acknowledge the lessons being learned about more holistic—and less drug-focused—treatment options.

But Lieberman is on very solid ground when he asserts that the nation’s health care system is holding back further progress. Major changes are needed, he writes, “to offer people the full potential of the therapeutic capacities we now possess.”

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.