Truthdiggers of the Week: Laurent Beccaria and Patrick Saint-Exupéry

The editor and publisher of the French journal XXI show that in France and America, journalism is not dead -- though the common wisdom is trying to kill it.The editor and publisher of the French journal XXI show that in France and America, journalism is not dead—though the common wisdom is trying to kill it.

Every week the Truthdig editorial staff selects a Truthdigger of the Week, a group or person worthy of recognition for speaking truth to power, breaking the story or blowing the whistle. It is not a lifetime achievement award. Rather, we’re looking for newsmakers whose actions in a given week are worth celebrating. Nominate our next Truthdigger here.What to do?

The question has tormented editors and publishers since the turn of the millennium, when the means of delivering information began their rapid expansion to the computer screen. The best answers did not present themselves immediately, and early on, the outcome of every cautious step was never certain. “Pressed by the Internet’s major players,” write Laurent Beccaria and Patrick Saint-Exupéry, “newspaper and magazine publishers have advanced over shifting ground, and their erratic course has often turned panicky.”

The two men are the publisher and editor, respectively, of the French general interest quarterly, XXI. Their comment first appeared in an insert in the Winter 2013 issue of their magazine and was republished in the “Readings” section of the October issue of Harper’s Magazine. The full piece, appearing under the title “Content and Its Discontents,” is in every sense a manifesto for the preservation and support of journalism in the Internet age.

What distinguishes Beccaria and Saint-Exupéry as pioneers of their trade? Their name provides a clue. The answer centers on a deep commitment to the shape of journalism in the 21st century and includes an understanding of the typical journalist’s experience as it has evolved under the influence of unregulated market forces.

“Journalists are subjected to what psychologists call paradoxical injunctions, that is, contradictory obligations,” they write. “They are expected to keep up with the exhausting reactivity of the Web … to exhibit professional mastery of a demanding range of media… and to conform both to journalistic ethics and to the exigencies of click tallying. … They participate in countless seminars, where PowerPoint presentations teach them more about corporate jargon than about their profession. Working under the auspices of a ‘media brand,’ which is increasingly a bazaar where everything’s for sale and contradictory promises are the order of the day, journalists lose their bearings.

“In a world where readers are referred to as ‘information consumers,’ ” they continue, “the outlines of a new profession — what may be called the ‘information technician’ — begin to appear. The job entails calibrated, duplicated, formatted writing; the triumph of changing opinions and ‘buzz’; confusion in communication; and marketing at every stage.”

If this is not bleak enough, the horror deepens upon consideration that the management of journalism has been usurped by people whose chief concern is profit. “Some start-ups even propose automating editorial tasks,” the duo continues. “The Chicago-based company Journatic has assembled an immense database of available news items and identified all the sources of fresh news (businesses, enterprises, associations, police reports, etc.), which it uses to provide ‘content’ in the form of thousands of articles a month to media companies and marketers. The company’s software continuously scans its database and the flow of news from its sources to produce articles that a battery of editors, English speakers who often reside in developing countries, rewrite for a few dollars, sometimes appending to their articles vaguely Anglo-Saxon pseudonyms.”

If you can’t guess at the economic fate of this new breed of “journalist,” Journatic’s founder is available to help: “If we reprocess a press release,” he is quoted as saying, “then why would anyone pay reporter-type wages to do that?”

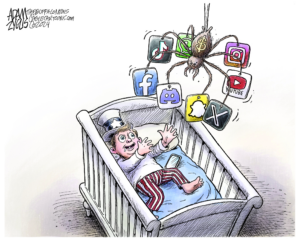

Go to the economics department of Journatic’s nearest university and say that out loud and my money says you’ll hear restrained murmurs of approval. From the second half of the 20th century on, economists at the University of Chicago have spread the notion that driving wages down to their minimum possible value is both a social necessity and a moral good. They hail from the same class of experts that tells us that all journalism is now wholly dependent on advertising. It includes the CEOs of companies such as Google, Facebook and Twitter — firms that make much, if not the bulk of their revenue on advertising. Young audiences, they say, will never pay for information they can get for free elsewhere. Common experience suggests they are right. But it’s not the case for all readers, Beccaria and Saint-Exupéry respond, and where it is true, it is largely because enough publishers have bought into the idea that generic, “content” — rather than complex, insightful reporting, is what readers want.

The success of magazines like XXI challenges this claim. In a letter in the October issue of Harper’s Magazine, Publisher John R. MacArthur praised Beccaria and Saint-Exupéry for defying “the conventional wisdom about the free-content model and [turning] XXI into the most dynamic, and perhaps the most profitable, new magazine on the European scene.”

“Although it does have a website,” MacArthur writes, offering a fuller sketch of the magazine, “you cannot read XXI on a computer — you must buy the print edition for the equivalent of about twenty dollars a copy at a bookstore or get it through the mail. The quality of XXI is guaranteed not by fickle marketers suffering from short attention spans but by faithful readers whose powers of concentration — whose appreciation for the elegant sentence and the hard-earned insight — have survived the onslaught of the Web’s unedited mediocrity.”For lovers of complex and engaging reporting, MacArthur’s analysis is heartening. But it leaves unanswered the question of whether XXI’s success is sustainable, and whether it can be replicated in the United States by publications that don’t carry water for the dominant culture. Beccaria and Saint-Exupéry’s answer? In addition to creating valuable journalism, success depends on how aggressively, intelligently and rapidly like-minded publishers pursue a unique and committed relationship with their readers. The vision is passionately expressed in their essay:

The press will never again be the megaphone it once was, capable of reaching millions of readers. There is no dominant medium anymore, only a bewildering welter of noise and information. By bowing out of the race, a renewed press can be a medium of depth, and it can speak as an equal to all those who want to open themselves to the world.

A reader isn’t an abstraction reducible to what he buys, his level of education, or his professional status. A reader is a man or a woman, young or old, lighthearted or serious according to circumstances, and always with his or her own different, individual tastes and background and knowledge. It takes time to forge reciprocal ties, but regaining readers’ trust day by day is one of the great joys of this profession.

More specifically, the duo’s vision of a reformed press rests upon four commitments: ample time (“Journalists must take the time to investigate — to let the scene sink in — and they must learn to work against reflexive emotions.”); intense investigation of the field (“By providing details, by evoking colors and smells, by renewing emotions and shining light on facts left in shadow, journalism must give life to what doesn’t exist in the media turbine.”); attractive presentation (“We must take advantage of [the] opportunity [to] reinvent portfolios and text-image associations that will speak to contemporary readers.”); and coherence (“Journalism that distracts and numbs, that heaps together everything and everything’s opposite, is journalism dragged into a system of convulsive gears.”).

If these words sound idealistic, it’s because they are. And they should be. It is not the pioneer’s job to accept what is, but to imagine what could be and isn’t yet, to cast it into clear, compelling relief, to throw their full weight into its urgent realization, and watch what happens. Some of the West’s newsmakers are grasping that an economic model based mostly on advertising can support only a few major institutions. Many of them have kept a tenuous, anxiety-ridden hold on their presses over the past decade only by means of the largesse of wealthy individuals committed to their cause or the charity of devoted readers. Under deteriorating economic conditions, both models have a limited shelf life; neither guarantees the survival of real journalism.

Where does all of this go? Even the experts don’t know. But Laurent Beccaria and Patrick Saint-Exupéry have given us an exciting vision that could sustain some publications. For imagining a new and better practice of the press, we honor them as our Truthdiggers of the Week.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.