Truthdigger of the Week: Tomas Young

When he dies this spring, Iraq War veteran Tomas Young will have spent his final years struggling to expose the guilt of those who make a holiday of the deaths and suffering of the powerless.

If you hadn’t heard of Iraq War veteran Tomas Young before this month, chances are you have now. Two weeks ago, Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges wrote about Young’s decision to escape the unbearable pain of his war injuries by starving himself to death. This week Truthdig published Young’s “Last Letter,” a message to President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney in which he damned those men for leading Americans, Iraqis and many others into hell via the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The piece — a paragon example of contemporary whistle-blowing — has attracted more than 600,000 views on Truthdig and the story reached millions as it appeared in major news venues worldwide. Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer called Young’s letter “the defining obituary on the Iraq War.”

Look below any of the articles that featured Young this week and you’ll find an audience that was saddened and angered by what it had read. Deeply upset by the deadly attacks of 9/11, Young answered the call to defend his country. As with so many like him, his patriotism was exploited to deliver money and power into the hands of American businessmen and politicians. Crippled by an ambush in Sadr City, Iraq, on April 4, 2004, Young faced a decade of paralysis, exhaustion, bedsores, exposed bones, difficulty breathing, an inability to eat, the eventual loss of his voice and removal of his colon and erectile problems, stuck in a body that would become the site of an increasingly pernicious chemistry experiment as he attempted to manage increasing discomfort with painkillers. At the conclusion of that period, he resolved to end his agony and total helplessness by fasting until death brings deliverance.

Young became a national figure with the award-winning 2007 documentary “Body of War.” The movie was the product of independent filmmaker Ellen Spiro and Phil Donahue, a former MSNBC host driven from the network for his passionate commitment to liberal values. The movie follows Young’s struggle to live with his injuries, and his successful effort to become a prominent member of the U.S. anti-war movement. He was encouraged to speak out by the example of another activist, Cindy Sheehan. Sheehan’s son Casey was killed in Iraq on the same day an AK-47 bullet pierced Young’s spinal column. For a few years, Young numbered among a chorus of veterans and people of conscience loudly opposing the war.

But in time his voice was hushed. In 2008, four years after his injury, Young suffered an anoxic brain injury after he was prematurely released from a Veterans Affairs hospital. He lost considerable control over his fingers and much of the strength in his upper body. His voice was so distorted that when he talked, people assumed he was mentally disabled. The injury left him even more dependent on others, chiefly his second wife, Claudia Cuellar.

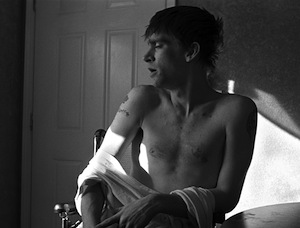

Celebrated New York-based photographer Eugene Richards knew Young before his second injury. He took photos of the veteran for a series published by The Nation called “War Is Personal” in 2006, while Young was doing “Body of War” with Donahue. Young was leery of the media, Richards recalls. Apparently owing to Young’s exhaustion, it took a few stops at his home in Kansas City, Mo., before Richards was able to meet him. When he did, he found the 26-year-old completely out of sorts. Young had a tough time keeping his head above his body, which was covered with burns from the cigarettes he could not always keep in his hand. He said he had taken a double dose of his medication by accident.

The photos confirm Young’s condition. Richards says he hesitated to publish them. “Tomas,” he recalls saying to Young over the phone, “I’ve got to tell you, you look like shit in my photographs.” The ex-soldier didn’t care. “They’re true, aren’t they?” he asked. “Yes, they’re true,” Richards responded. “That’s what counts,” Young said.

Richards recalled the story for Truthdig by telephone. “It’s quite impressive, because he wasn’t shy about his situation and didn’t want to hide the realities of what was going on with him and other people,” he said.

As the years went by, the two kept in touch, speaking every couple of months. Not long ago Richards returned to take photographs of Young and Cuellar. The change brought about by the brain injury was dramatic. The handsome man who previously sported close-cropped hair now wore a long beard. His voice was distorted, and worked only under considerable labor. He smoked more. “He was more distant than he’d been before,” Richards said. “I’m sure he was troubled by his inability to speak. But he was very friendly.” Richards took a handful of photographs for the couple. He said that by then Young had made the decision to stop living. “He told me very tactfully that he was considering a change in his status, so to speak,” Richards said.

The photographer recognizes that the pain of being unable to socialize was a determining factor in Young’s decision to die. “I think one of the worries he had [after his brain injury] was that people wouldn’t talk with him as much as they used to,” he said. Young’s independence was already gone, but the inability to participate in the sort of nuanced communication that constitutes so much of interpersonal relating stands as yet another grievous, isolating loss.

A number of people commenting beneath the many published articles about Young this week have written that suicide, even in Young’s condition, is inexcusable. “I’ve met other people who have terribly debilitating diseases, but the consciousness is still there,” Richards said. “Tomas is becoming trapped. His world is shrinking.” Richards is tempted to try to persuade his friend to abandon his decision. “I would love to get on the phone and argue with him,” he said. “I would because I care for him so much. But on the other hand, what he calls life is progressively coming to a close for him. It’s kind of pretentious on my part to think that my idea of life applies to his. He’s been thinking about it for a long time, and I think life is closing in on him very quickly.”

For a moment Richards thought about the consequence of Young’s coming absence to liberals across the country. “One of the biggest problems for me, a practical problem,” he confided, “was that we’ll lose a major voice that is questioning these fucking wars. We won’t have that voice much longer. That sounds so selfish, but it’s real.”

The prospects for individuals in the kind of trouble Young has endured for almost a decade are never good. A few years ago Richards published a book of photographs of people who were heavily involved in drugs. Today, he said, every person who appeared in that book is dead. Coincidentally, the subjects of “War Is Personal,” the book in which Young appeared, are moving in the same direction. At age 33, sometime in May, a month after quitting his nourishment regimen, it is forecast that Young will die too.

For struggling for as long as he has, for publicly shaming a class of people who make a holiday of the deaths and suffering of the powerless, and for forcing us again to consider the terrible consequences of America’s unnecessary, ongoing and disgraceful wars, we honor Tomas Young as our Truthdigger of the Week.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.