Truthdigger of the Week: Michael Paarlberg

After leaving a trail of dead in the private sector, the “long and steady march toward a fully disposable workforce” has turned sharply toward the public sector in recent years, the labor scholar tells us in a column for The Guardian. After leaving a trail of dead in the private sector, the “long and steady march toward a fully disposable workforce” has made a sharp turn in recent years toward the public sector, the labor scholar tells us.

After leaving a trail of dead in the private sector, the “long and steady march toward a fully disposable workforce” has turned sharply toward the public sector in recent years, the labor scholar tells us in a column for The Guardian.

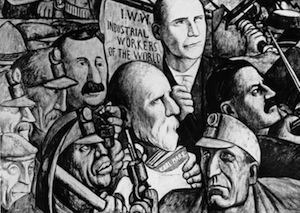

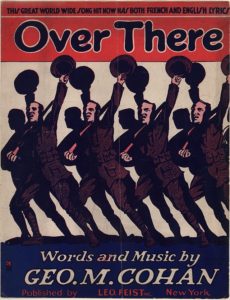

Union membership in the United States is at its lowest point in nearly a century, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported this week. Just 11.3 percent of all workers have the possibility of representation at a negotiating table — the same share that existed in 1916. “To put this in proper historical perspective,” writes Michael Paarlberg, a lecturer in government at Georgetown University, “union members are as rare today as they were at a time when being one could get you shot to death in a mining camp by the Colorado national guard.”

It’s not that employees are demanding to be exploited. Surveys reveal that most wish they had a greater role in determining their working conditions, and that a majority of nonunion staffers would join a union if given the opportunity.

But they don’t get that chance today. Leaders of private industry have confidently opposed the right of workers to organize since Ronald Reagan made the subordination of organized labor into official government policy in 1981. Seven months into his first term as president, Reagan fired more than 11,000 air traffic controllers who were striking to seek better pay and a reduced workweek. The message was clear: The federal government would now protect business owners, not workers.

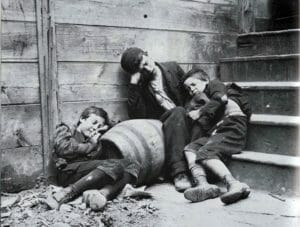

To make matters more worse for labor, in the time that has passed, “large parts of the economy” have shifted “toward part-time, temporary, low-wage and no-benefit jobs.”

Although union decline linked to deindustrialization “has been accelerating since the mid ’70s,” what’s new is that attacks on unions are now concentrated in government, “the last bastion of organized labor.” When organizers moved into the public sector after the carnage of private labor, they assumed guardian roles over “what were then seen as stable jobs: teachers, firefighters, cops, state-funded healthcare and childcare workers.” Not so today.

With the onset of the recession, “a new breed of Republican governors … seized the moment as a chance to punish their political opponents,” Paarlberg observes. With a swiftness that rivaled Reagan, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker wasted no time in passing a law to shred state workers’ bargaining rights. Enormous protests erupted amid the battle as the conflict attracted far more people than were directly involved in unions. Activists became exhausted and lost after four months of agitation in the state Supreme Court. But in 2012 judges ruled that Walker’s law violated state and federal constitutions.

Though it lacks broad government support, the spirit of labor is not dead. 2012 saw labor activism on the rise. “Last year,” Paarlberg writes, “two of the highest profile labor actions in the country — one-day ‘flash’ strikes at fast food restaurants in New York City, and at Walmart stores nationwide — were coordinated by groups that are not traditional unions: New York Communities for Change and OUR Walmart (though both received union support). And both strikes were carried out without the traditional aim of formal union recognition.”

“Networks of new, grassroots workers centers … have grown in sectors which unions have found nearly impossible to organize due to their contingent or informal nature. And their victories — exposing safety and health violations, winning raises and backpay owed to workers, freeing some from virtual domestic slavery — have been achieved largely outside the purview of the body that governs union elections, the National Labor Relations Board.”

Other victories in recent years have been won outside of the negotiating room, through class action lawsuits and legislation at the state and city level. They include “winning paid sick leave, overtime, and disability compensation, and forcing cities to budget proper funding to enforce wage-hour and health and safety laws.”

“These victories are significant,” Paarlberg notes, “and translate into safer jobs and more food on the table for workers. But it’s important not to lose sight of what is being lost: an institution of collective agency, and a way for employees to sit down with employers on equal terms and set the conditions for what they will do for eight or more hours every day. The disappearance of that institution and the breakdown of that balance of power between them create the very conditions — from discrimination to workplace accidents to outright theft — that these new worker movements rise up to address.”

For underscoring the necessity of institutional support for the large numbers of Americans struggling to obtain a decent income, health and retirement benefits, time for themselves, and the dignity, happiness and confidence that only these possessions make possible, we honor Michael Ahn Paarlberg as our Truthdigger of the Week.

(A paper for which Paarlberg is well known argues from research that the federal government has failed in its self-prescribed duty “to set and enforce high standards for the treatment of” workers employed through companies the government does business with. “Instead of helping to create quality jobs,” he finds, “all too often the federal government contracts with companies that pay very low wages and treat their workers poorly.” Read it here.)

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.