Truthdigger of the Week: Andrew Cockburn

In reporting on decades of U.S. sanctions against Iran, Harper’s Magazine’s Washington editor fully uncovers a mass destruction and murder scheme on a Napoleonic scale.

Every week the Truthdig editorial staff selects a Truthdigger of the Week, a group or person worthy of recognition for speaking truth to power, breaking the story or blowing the whistle. It is not a lifetime achievement award. Rather, we’re looking for newsmakers whose actions in a given week are worth celebrating. Nominate our next Truthdigger here.

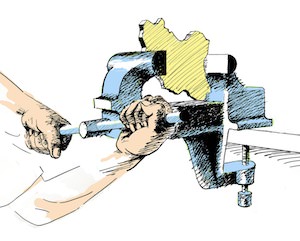

War is not fought with bombs and bullets alone. Nations can be wrestled into submission or degradation by economic means, namely heavily penalized general or specific prohibitions on trade between companies and a target state. These sanctions, which are the equivalent of a siege in wartime, are a favorite tool of the United States, which has 23 such programs ongoing today, “a living memorial to the national-security preoccupations of past decades,” Harper’s Magazine Washington editor Andrew Cockburn wrote in that publication’s September issue.

Sanctions do not always need to be the devil’s tool. They can be used smartly against genuine threats with minimal damage to innocent parties, if any at all. But U.S. leaders have used them to devastating, unconscionable effect. A favorite example of critics is the reported deaths of at least half a million Iraqi children under sanctions imposed by President George W. Bush and retained by President Bill Clinton. Clinton’s Secretary of State Madeleine Albright famously told CNN interviewer Lesley Stahl those deaths were “worth it.” As Cockburn wrote, that number is far more than “estimates of the total death toll from subsequent violence — a still horrific 174,000.”

While he toured a ward of “sickly, wasted infants” in Iraq during the first summer of sanctions after the Gulf War, one hospital staffer cried to him: “No Iraqi babies invaded Kuwait, so why must they suffer?”

Proponents of the practice are concentrated most potently in the Office of Foreign Assets Control, the department of the Treasury that conceives, writes and executes sanctions law, according to one Washington attorney who spoke to Cockburn. The office peddles its product as “a heck of a lot better than war.” But Cockburn, whose meticulous scholarship comes through at every point in his Harper’s article, knows better. “Just as air power has evolved from the area bombing of entire cities during World War II to ‘precision’ drone strikes,” he writes, “so the theory and practice of sanctions has evolved from straightforward blockades into a more ambitious and intricate system known as ‘conduct-based targeting,’ aimed at the economic paralysis of thousands of designated … people, companies [and] organizations.”

“Drone operations attract widespread comment, inquiry, denunciation,” he continues. But America’s “modern economic warfare, though it bends the global financial system to its ends and can blight entire societies, operates well below the radar, frequently justified as a benign alternative to military action.”

So what has the United States done to Iran? The U.S. first targeted the country after the takeover of the American embassy in 1979. In consequence Iran lost 60 percent of its oil exports, the ability to freely spend money earned from remaining oil sales, insurance for its transport ships and the ability to participate in the international banking system. The result was and continues to be the contraction of the nation’s economy and gathering inflation. As is clear, these limitations do not affect the government alone.

Just a fraction of the rest of the offenses read like a sadist’s grocery list. Three thousand Iranian cargo ships are stranded, meaning food and medicine — which are “theoretically exempt from this blockade” — are virtually impossible to import. Americans who inherit an Iranian business are candidates for arrest. Anyone subject to U.S. laws faces “jail time for exporting medical equipment to Iran or investing in an Iranian certificate of deposit.” Costco recently reported it had allowed six employees of targeted Iranian institutions in Japan and Britain to patronize its stores. The company “duly struck” the customers “from its membership rolls.”

Negotiations under President Obama, who early on expressed an interest in pursuing diplomacy with Iran while maintaining “targeted” sanctions, blocked the acquisition of highly enriched nuclear fuel necessary for the production of medical isotopes to treat 850,000 Iranian cancer patients. Fuel shortages resulting from the targeting of gasoline imports in 2010 made it harder for ordinary Iranians to get around and forced drivers to use low-quality, locally refined gasoline, which made pollution worse. In 2011, sanctions were imposed on any foreign bank that made oil deals with the nation’s central bank. “In 2012, Obama signed the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act, cutting off access to the U.S. market for any foreign company doing business with Iran’s energy sector and freezing any American assets they might have.”

Other recent legislation has targeted all remaining Iranian oil exports and choked off the country’s access to dwindling foreign currency reserves, which are necessary to reduce the costs of international trade. One rejected provision sought to punish “relatives of sanctions violators, including uncles, nephews, great-grandparents, great-grandchildren, and so forth.” In the past year, Iranian currency collapsed from 16,000 rials to 36,000 — the precise hoped-for outcome of the sanctions plan. The price of a kilo of low-quality minced meat recently doubled in the course of a week to a day’s pay for an average construction worker.The list ends with “echoes” that Cockburn says “recur in less statistically obvious ways. Aircraft are crashing in greater numbers, largely because of an ongoing shortage of long-embargoed spare parts. Crime and drug addiction are growing exponentially, there being absolutely no shortage of narcotics, especially heroin from nearby Afghanistan, but also cocaine, the perquisite of the rich. Just as sanctioned Iraqis found a class of “new billionaires” flaunting their wealth in the midst of want, so sanctions are enriching a similar class of Iranians, not only drug dealers but smugglers, refinery operators, and other profiteers.”

The U.S. did not always use sanctions so effectively. Up until the mid-’90s, their fundamental flaw was that their effectiveness required the cooperation of other nations. Cuba survived decades of U.S. embargo because the rest of the world saw no reason to join in. That ended, Cockburn writes, “when the United States learned to use its dominance of the international financial system as a weapon.” David Cohen, undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence and the overall supervisor of American sanctions operations through the Office of Foreign Assets Control, described the tactic of threatening to block foreign banks’ access to U.S. financial markets if they dealt with Iranian banks as a “vigorous outreach and education effort.” An example of what happens to offenders was made when a Dutch bank received an $80 million fine for processing transactions for Iranian and Libyan banks. Total fines for sanctions infractions by foreign banks have risen to hundreds of millions of dollars in recent years. In order to prevent unwitting violations, many banks and major corporations hurriedly expanded their “compliance” departments, a trend that brought OFAC veterans directly into their offices, serving to reinforce this new particular culture of compliance.

Thanks to the embedding of a slew of what Cohen calls “innovative tools” in corporate, legal and governmental organizations, an unquestioning disposition in favor of sanctions has developed in a new, resilient bureaucracy. And its aims are described in the most irritatingly establishmentarian language, conspicuously proud of itself amid its indifference to the human havoc it causes. “We have in place now,” Cockburn cites Cohen declaring in September 2012, “an enormously powerful set of sanctions at home and around the world. It retains its essential conduct-based foundation as it broadens out to target an ever more comprehensive set of Iranian commercial and financial activities.” Members of Congress love it too, as sanctions present a de facto way to wield another foreign policy.

The people who wage undeclared war with sanctions are transparent about their aims in the enthusiastic manner we’ve come to expect from the ideal American businessman-cum-barbarian. Mark Dubowitz, the executive director of the Orwellian D.C. think tank the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, informed Cockburn that “the aim of sanctions is to try and bring the Iranian economy to the brink of economic collapse and, in doing so, create fear on the part of the Supreme Leader and [his Revolutionary Guards] that economic collapse will lead to political collapse and the end of their regime. … We’re trying to break the nuclear will of a hardened ideologue.” This is simple business to ambitious men like Dubowitz, and they want the admiration and rewards that come with a job well done. And an expanding sanctions bureaucracy means that sanction imposing has become a pursuit unto itself. Exhibiting similar amorality about what they were doing, comments made by CIA officials involved in the Iraq sanctions of the ’90s led Cockburn to write that “the impoverishment of Iraq was not a means to an end, it was the end.”

Cockburn tells the story of a massive bureaucratic weapon that, for the the majority if not all of its existence, has been used by petty functionaries seeking to build their careers and people in business looking for legal ways to manipulate markets to the effect of maintaining and increasing their control over profits. Although the machine is impersonal, the consequences are deeply human, and in the ugliest ways imaginable. Many of the “hordes of skinny and bloated children” who survived the sanctions imposed on Germany after World War I grew up to support a dictator who promised them deliverance from their suffering. U.S. leaders have helped build identical conditions in the Middle East since World War II, offering evil more than enough opportunities to enter the world through the minds and bodies of desperate people. For giving the public a chance to grasp one of the ways this is happening, we honor Andrew Cockburn as our Truthdigger of the Week.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.