Tony Kushner on Suffering Actors, the Wayward Left and the ‘Dream’ of Revolution

For someone who finds writing tortuous, Tony Kushner does a lot of it. Tony Kushner poses at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis in 2009. AP/Craig Lassig

Tony Kushner poses at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis in 2009. AP/Craig Lassig

For someone who finds writing tortuous, Tony Kushner does a lot of it. Probably best known for his two-part epic, “Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes,” Kushner’s other plays include “Slavs!,” “Homebody/Kabul,” “A Bright Room Called Day” and “Caroline, or Change.” He also wrote the screenplays for Mike Nichols’ film version of “Angels in America” and Steven Spielberg’s films “Munich” and “Lincoln.” Kushner, who has won three Obies, an Emmy and a Pulitzer Prize, recently came back to Berkeley Repertory Theatre, where seven of his plays have been produced, for the West Coast premiere of his latest, “The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures” (his husband nicknamed it “iHo”).

The play, directed by Kushner’s longtime collaborator Tony Taccone, the artistic director of Berkeley Rep who co-directed “Angels in America,” tells the story of a family in Brooklyn whose Communist longshoreman father has decided to commit suicide. It runs in Berkeley through June 29.

Out in Berkeley for rehearsals, Kushner talked about how with plays we watch actors suffer so we don’t have to; Taccone’s fearlessness when collaborating on “Brundibar,” a children’s opera originally performed in a concentration camp; the toll “Death of a Salesman” took on the late Philip Seymour Hoffman; the ability of democracy and elections to bring about radical change; and his frustration with leftists dismissing government rather than trying to transform it. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Emily Wilson: Do you find it fun to get to rework plays like you’re doing with this one?

Tony Kushner: I never find any writing fun. It’s all torture. It’s gratifying — it feels like this is what I didn’t understand the first time out and now I understand — maybe I’m just slow. I love having the opportunity to do that, when you do a film that was one of [the] great shocks. The first time I did a film was Mike’s version of “Angels,” and then I did the two movies with Steven, and I didn’t realize that every day of shooting you put another scene in the can. What that means is one after another, scenes you’ve written are gone, and it’ll take its final shape in the editing room. There’s a constant sense of loss even if the filming was fantastic.

I’ve been really lucky in the three things I’ve done so far, and I’m really proud of them. You know, we’re watching Daniel [Day Lewis] do these unbelievable things in “Lincoln.” Like the big Cabinet speech where he talks a long time for a film, and watching him do that for me and for many of the other actors was one of the most electrifying things I’ve ever sat through because he’s so fantastic, and I’m very proud of that, but no one will ever do it again in another way. You don’t have that experience at all in theater. The play keeps going on. Since I own it, I get to do my thing with it, and it keeps it up in the air in a way I find gratifying or pleasurable, although a show like this is backbreaking in a lot of ways.

EW: How is it backbreaking?

TK: It’s a long play. It’s a very dark play, and I think emotionally it’s the most painful play I’ve ever written. There’s a struggle in the play between despair and hope, and between a belief in progress and a belief in revolution, which I think is a conundrum at the center of the progressive political soul. It’s a family drama, and it’s a pretty unhappy family. It’s pretty dense although you don’t have to know anything at all. If you just come and don’t panic and listen, you’ll be fine. We’ve all worked very hard to make sure people are taken care of. You don’t have to be an expert on any of the pretty arcane things some people are discussing to follow it, but it’s not an easy play to do.

It’s very hard for the actors. I don’t know how actors do it, and they have to do it eight times a week. If you’re really going to do a play, you don’t figure out a shorthand way of doing it. You have to go there every single night. This is what actors do, and I don’t understand how they stay sane, and of course, many of them don’t. You see them at the end of a long rehearsal, and they look like they’ve been run over by a Mack truck.

When Mike’s production of “Death of a Salesman” was on Broadway, I hosted a benefit at the Library of America, and I asked the cast to do a benefit, and they came out and did a Q&A with the audience. With Phil Hoffman especially, it was just incredibly clear the toll that “Death of a Salesman” was taking. He wasn’t playing at somebody who was suicidal. In the part of Willy Loman, he took Arthur Miller at his word and didn’t show a guy nobly suffering but a person who was actively suicidal, which is a very strange mental place to be. You’re actively severing your ties to the earth, and it’s not entirely attractive to look at. It was in some ways the truest versions I’ve ever seen.

Then he came out and one of the first questions was, “Do you think you’ll ever get Willy Loman out of your head?” and he said, “Well, there’s a thought.” He looked like someone had spoken his worst nightmare. So it’s very costly. They’re going to a place emotionally, and it’s not possible that on some level that doesn’t take a toll. There’s the sacrificial animal part of theater. We’re watching people suffer so we don’t have to. EW: Do you believe in catharsis in the theater?

TK: I’m a child of Brecht. I revere him. I think he was one of the greatest playwrights who ever lived, almost always badly done. He’s a poet, and he created a genuinely significant body of theoretical writing. I’ve translated “Mother Courage and Her Children,” and I think it’s one of the most heartbreaking plays ever written, and the idea of catharsis and an enlisting of empathic faculties for the rehearsing for an audience of terror and pity, it’s part of the process.

He’s looking for a way to understand the world through Marx. And what Marx says is to understand the world, you have to look beneath the surface and that what we see as the surface, which is disguised as the natural, is actually an entirely constructed system that hides what’s really going on, which is a system of human relationships involved in the manufacturing of the world and the manufacturing of value, in which some people get a lot and some people get very little. And it has nothing to do with the amount of their lives they’re expending in this creation. It has to do with ownership of property and grotesque imbalances in wealth and not just in human misery because of poverty, but an almost spiritual affliction that’s visited on the people whose laboring lives are stolen from them.

To look and see that’s what’s really under an iPhone, takes a kind of seeing, and what Brecht understands, as Shakespeare did, is that’s why we go to the theater — because it shows us this magnificent surface and demands that we look beneath the surface at the same time — and that double vision and critical consciousness which not just Marx, but everybody including Aristotle and Plato, said you have to develop or you’re just a fool. Life will be handed to you and you’ll be entirely its victim.

EW: What do you like about working with Tony Taccone?

TK: Directing is this kind of paradoxical thing of guiding and setting free. It’s like really great parenting — if you over-guide and protect your child, they’re going to turn into a hothouse flower who can’t set foot into direct sunlight, and if you don’t guide them at all, they’re going to turn into some sort of feral creature. That balance is hard to do, and he’s really great at that. Tony has a wonderful spirit and a great sense of humor, and we make each other laugh.

He’s also kind of fearless. I remember when we did “Brundibar,” one of the greatest works of children’s theater ever that was performed in Terezin, a concentration camp, and the composer, Hans Krása, was killed in Auschwitz. It’s only half an hour, so you need something to go with it. I had found this opera called “Comedy on the Bridge.” It’s almost an hour long, and it’s a very adult piece of music. It’s about adultery really — it’s not for kids. Maurice [Sendak] did this fantastic set, but we saw while the kids loved “Brundibar,” “Comedy” was over their heads. So we were about to do it in New York, and I thought this is just a mistake, and I’d always been haunted by the story of how the score got into Terezin. Krása wrote it outside and then he got taken to Terezin, and he didn’t have the score with him. Someone smuggled it in his suitcase when he was arrested and taken to the camp.

They had just packed up the sets on Monday and were going to unload them in New York on Friday. So on Monday night, I sat down and wrote a curtain raiser for “Brundibar” about the smuggling of the score in, and I was really pleased with it. I called Taccone on Tuesday morning, and I said, “You’re going to think I’ve lost my mind, but if you could come here and find a little girl to do this we could do this and drop “Comedy.” He read it and said, “I love it, but it’s incredibly crazy, and we can’t do this.” Then he came out early, and we found a girl who was fantastic and we loved it, but we were still leaving the option to do “Comedy.” The cutoff was 5 o’clock on Friday. By then the Teamsters had to load the sets off the truck and if they did, we were doing “Comedy.” If they didn’t, we were doing “But the Giraffe,” my play.

We had a read through Friday afternoon, and I was losing my nerve, and Maurice was having a nervous breakdown. I said to Tony, “You’re the director, you have to decide,” and we would go back and forth. At 5 to 5, literally in the middle of a conversation, he said, “Oh, fuck it!” and he stood up and popped open his clam phone and called the production manager, and said, “Leave the sets on the truck.” And we did it, and it was fantastic. It changed everything. The kids loved it, and people were crying. Most responsible people would have said, “Oh, we can’t.” But there’s a part of him that loves shutting his eyes and holding his nose and jumping into mid space. Sorry — that took forever — I’ve never told that before. But things like that, it’s thrilling. So I love working with him.

EW: It says in the literature about this play that it deals with, among other things, the paralysis of the left. How does it do that?

TK: The play certainly came out of something I’ve been saying publicly for some time and wrestling with. ‘The left’ is a big word — it’s a multi-headed creature with unspecified boundaries. I think of myself as a person of the left, and I identify almost tribally with the left. It’s a term that means something to me, but I’ve been sort of critical of the left.

It started for me around the time of the Iraq War when I spoke at this enormous rally before the bombing of Baghdad started. I think it might be the largest march in the history of New York City — it was at least a million people. It was really cold, below zero, as I remember it, and these people were so distraught and horrified by what was about to be done by America. They came out in the digital age, and they were on the street protesting to say, “We don’t want you, Bush, to do this.” I had this feeling while I was staring at this immense sea of people that I didn’t quite believe that this was going to accomplish anything. Then the next day Bush said about the demonstrations, “Well, it’s sort of like a focus group.” People got very angry, but I think it’s one of the only recognizably true things the little shit ever said, because that’s exactly what we were. We had no more power than an advisory group that people who did have power were completely free to listen to or, as was likely, to ignore.

I remember that horrendous feeling of falling headlong into the abyss as we saw this thing coming, and The New York Times and everybody else were saying it was a good idea, and people who should know better had for some reason forgotten who was going to be commander-in-chief. All other concerns aside, it’s not going to work if the people running the thing are sociopaths and criminals — it’s just going to go badly.

Sometimes you’re going to have people in the White House who just cannot be handed this extremely dangerous tool. There’s never been anybody in the White House who that’s ever been more true of than George W. Bush. His entire record shows he had no understanding of what death was, he had no normal regard for human life, he executed more people than anyone. So it was a horrible time, and I went to a lot of anti-war demos and teach-ins.

I remember going to one teach-in in Cooper Union after the bombing had started, and this guy said, “The Congress can’t help us, the president isn’t going to help us, we have to take to the streets.” And I thought, “What are you talking about?” That isn’t going to happen in any time that’s going to mean anything to the people of Iraq, and you’re saying Congress isn’t going to help us. Yes, manifestly, the Senate had just handed over war powers to Bush. So it was like, sure, go ahead and create mayhem in this imponderable crazy way.

And the more I thought about it — I think Barack Obama is a great president, and the left has responded to him since day one, and God knows it has not let up since — there’s just been what I consider to be this profoundly dangerous willingness to speak with a shocking recklessness about this administration, and to dismiss it over and over as being no better than Bush. There’s no sophistication about politics and how power works in a democracy. It feels to me that we’ve been in complete exile ever since the Clinton era, and we have found this very dangerous place for people to find when they’re citizens of a democracy, which is we became critics. And if you don’t have power, it’s terrible on one level because you can really get fucked over, but it’s also great because if you don’t have to make compromises in terms of ideology, you can be completely pure in what you believe and be absolutely appalled by any variance because you don’t have to do anything. You just sit back and criticize the people who do.

The fact that we have recovered economically, that we have universal health care, is never even talked about. We screamed and yelled about him saying, “I need time to evolve my feelings about gay marriage.” There’s no way on earth that Barack Obama, a constitutional law scholar, didn’t understand the difference between religious marriage and a secular institution. Could an African-American man in 2008 elected as president have come out for gay marriage? Would you rather have had a Republican in the White House in 2008 and 2012? When he decided to support gay marriage, he picked exactly the right moment, and it worked.

I feel like this is frequently the history of the left, and it’s become increasingly that. People I admire enormously who I think do incredibly important work are being critical — but you really want to have the NSA brought under control? Get rid of the fucking Patriot Act and get a Congress that could actually work as opposed to what we have now, which is a Congress so overburdened with tea party insanity that it literally can’t do anything. The checks-and-balances system is still as far as I know kind of the best idea for how to make a machine for self-governing if the people participate.

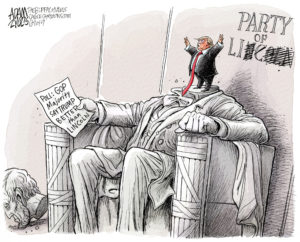

But then the people have to participate. If we run around yelling and screaming the government is of no interest, in what way are we different than Rand Paul? Or Ron Paul? We’re just a different form of anarchism. Left anarchism has a very lovely, powerful history, but anarchism is insanity, I think. Law is an expression of a collective will if it’s just law. If you get lucky, unbelievably lucky, and you get an Abraham Lincoln or a Barack Obama, count your fucking blessings. It doesn’t mean you don’t criticize them, but you make sure your criticism doesn’t rise to such a level that only when the Republican candidate is stupid enough to get caught on tape saying he doesn’t give a shit about 47 percent of the country, do you win re-election for a Democrat.

We’re going into a midterm now, and if we lose the Congress, a lot of things will have contributed to that, but there’s an unceasing din of very principled, very sincere people on the left, and this vast, very important energy is not going into making sure we get control of the Congress, get control of the executive branch, get control of the Supreme Court, and roll back Citizens United, which has to be overturned soon. Unless you really have belief there is going to be some kind of revolution that overturns the U.S. government and gives us something better, and no one who isn’t psychotic could really say that that’s likely, we have to start to think about what the fantasy of revolution is, and I don’t mean to belittle it by that. It’s a dream, and it has immense power, and I hope this comes across in the play — it’s not dismissible and it’s not negligible — but in terms of a theoretical basis that guides us into action, why we don’t recognize how often in American history, electoral processes and a functioning democratic republic have brought us to radical transformation is incomprehensible to me.

EW: When has that happened?

TK: We have so many instances and we’re living through one now with LGBT rights. It’s something that it seemed like it would take millennia to turn the country around, and something happens, usually in concert [with] the street and the halls of power, you know, Selma and the March on Washington and the Voting Rights Act and the Great Society programs. Things can change and they can change radically and old baked-in forms of oppression and bigotry and racism and sexism — suddenly, they’re not so baked in, and why don’t we have more faith in that?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.