Tom Hayden on Mark Rudd

Forty years after he helped destroy SDS, Mark Rudd condemns his role in Weatherman as "the greatest single mistake of my life … a historical crime." How did it happen and what did it mean? Why did peaceful protest give way to violent resistance? What lessons are to be learned from the failure to spurn the seductions of charismatic cults?

Don’t go around tonight, Well it’s bound to take your life, There’s a bad moon on the rise.

— Creedence Clearwater Revival, 1969

The truth was obscure, too profound and too pure, To love it you have to explode.

— Bob Dylan, 1978

Anyone meeting Mark Rudd today would think him a nice level-headed guy: retired community college teacher, carpenter, husband, father of two, rank-and-file peace activist. Turning 62, his hair is gone white, the paunch protrudes, but the blue eyes are observant. All in all, laid back but present.

This is the same Mark Rudd I met in the heat of the 1968 Columbia University student strike, the Mark Rudd who ended a letter to Grayson Kirk, Columbia’s president, by declaring, “Up against the wall, motherfucker!”, the Mark Rudd who proudly led Students for a Democratic Society to close its offices and end its organizing efforts in the midst of the greatest student rebellion of the 20th century, the same Mark Rudd who went underground and supported a plan to bomb Fort Dix, which went awry and killed three of his friends — all by the time he was 22 years old.

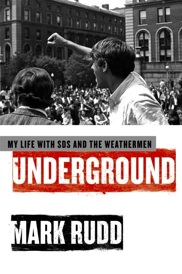

Rudd struggles to reconcile these two selves, representing two eras, in his memoir, “Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen,” an important contribution to a growing collection of narratives from former participants in the revolutionary 1960s’ underground. Other recent works include Bill Ayers’ “Fugitive Days,” Cathy Wilkerson’s “Flying Close to the Sun,” Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, and Jeff Jones’ “Sing a Battle Song,” David Gilbert’s “No Surrender,” Leslie Brody’s “Red Star Sister,” Roxanne Dunbar’s “Outlaw Woman,” and the 2002 Oscar-nominated documentary “The Weather Underground.” The saga is turned into fiction as well in Dana Spiotta’s “Eat the Document.” Other novels that mine the same or similar terrain include Heinrich Boll’s classic “The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum,” Susan Choi’s “American Woman,” Neil Gordon’s “The Company You Keep,” and Marge Piercy’s “Dance the Eagle to Sleep” and “Vida.” No doubt there will be more.

That may be more books than those devoted to such organizations as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or the Students for a Democratic Society, not to mention community organizing or the farmworkers’ movement of those years, and the genre is likely to grow, revealing an abiding fascination with the question of why it was that some peaceful dissenters turned to violence so suddenly in the late ’60s. The Weather Underground took credit for 24 bombings altogether and, according to federal sources, there were additionally several thousand acts of violence during the same years. In 1969-70 alone, there were more than 550 fraggings by soldiers, according to one authoritative historian of the Vietnam War.

The fascination with such violence is not new. Similar themes can be found in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s 19th-century novel about young Russian nihilists, “The Possessed,” in Joseph Conrad’s “Under Western Eyes,” Henry James’ “The Princess Casamassima,” Andre Malraux’s tale of the Shanghai uprising, “Man’s Fate,” and, of course, Ernest Hemingway’s stories of the Spanish civil war.

What explains the enduring interest in such radicals? I believe it has something to do with exploring the extremes of personal commitment. To fail heroically, though miserably, is seen by many as attaining a greater glory than the rewards to be had from the mundane life of patient political work. As Karl Marx wrote of the Paris Commune, the French Communards at least had stormed the heavens. And as Rudd quotes Erich Fromm quoting Nietzsche, “There are times when anyone who does not lose his mind has no mind to lose.”

Fiction may be a better vehicle than autobiography or history for ascertaining the truth in clandestine histories where the secret lives of others are at legal risk. In Rudd’s self-description, he is far from heroic, but more like a confused young man from the Jersey suburbs staggering out of a novel by Philip Roth, either “American Pastoral” or “I Married a Communist.”

There is an unconsciousness in Rudd’s memory of himself, a kind of bumbling innocence that will disappoint a reader seeking more. When, for example, the milling students at Columbia sought tactical direction, Rudd writes: “I had only the vaguest idea of what we were doing.” When Rudd is told by a comrade that his demonstration is out of control, he replies, “I know. I have no idea what to do.” When Rudd calls for taking a hostage, he says, “I meant a building,” not an administrator. But then he supports taking Dean Henry Coleman hostage, yelling: “Now we’ve got the man where we want him! He can’t leave unless he gives in to some of our demands.” When the media selects him as the new revolutionary symbol, he remembers a “gnawing sense that I was in over my head.”

Some of this is funny, as for example when Rudd calls his father in Maplewood, N.J., to say “We took a building” and the old man replies, “Well, give it back.”

But most of what Rudd tells is deeply disturbing, though illuminating, in its unemotional matter-of-factness. In describing the Weather Underground as a cult, Rudd writes: “I knew that the whole thing was nuts but couldn’t intervene to stop it. … I believed as much as anyone else, perhaps more so, in the need to harden ourselves through group criticism.” Feeling “addled,” he agrees to take a break from the national leadership and accept demotion to its New York collective. He is unable to tell us exactly why, writing only that he was experiencing “the competitive world of the Weatherman hierarchy from the underside now.” Yet he “couldn’t allow my conscious mind even a tiny doubt as to the direction of the organization.” The mindset becomes lethal. Rudd “assented to the Fort Dix plan when Terry [Robbins] told me about it.” He dropped off Robbins, one of the architects of the plan, at the West 11th Street townhouse in Manhattan two days before the bomb Robbins was assembling would accidentally go off, demolishing the site. Rudd spent March 6 at a friend’s house in New Jersey “to establish an alibi,” then watched “Zabriskie Point,” the Michelangelo Antonioni film in which a fancy bourgeois house is blown up. All this while three of his comrades were being killed by the bombs they intended for the noncommissioned officers, which would have included their dates, wives, and others, too, of Fort Dix.

Rudd, by his own account, often seems to be under the spell of charismatic, authoritarian leadership, vulnerable to the most fanatic of the fanatics, severed from his realities of only two years before. After the townhouse bombing, he meets a few weeks later with John Jacobs, known as JJ, an old friend from Columbia and the charismatic leader of the New York Weather faction, who wanted to kill soldiers and noncombatants. Rudd, who says he was befuddled, agreed to support JJ’s newest ideas: blowing up a B-52 on the ground, knocking out a government computer, or considering a “selective” assassination or kidnapping. Then he joins JJ in bed with a married woman who’d given Rudd a place to hide. He enjoys the “intense excitement at the thought that my semen was mixing with JJ’s inside a woman.” Later he tells the woman’s husband that “women’s liberation shouldn’t threaten him.”

There is much more, some of it extremely explosive, though unprovable, such as Rudd’s assertion that JJ was a willing scapegoat for the entire Weather leadership that approved, or, at the least, did not oppose, the Fort Dix plan. But recounting any more of Rudd’s story here will bring no more revelation, only a kind of nausea. Rudd in these pages resembles the Roth character who says, “Eve didn’t marry a communist, she married someone who couldn’t find his life.”

Yet I know Mark Rudd to be a good man, a useful person despite all this, and one must ask, how can that possibly be? Partly it is because I believe individuals are capable of surprising changes. I have befriended, and worked with, numerous people who have inflicted enormous damage on themselves, their loved ones, and society at some stage in their past lives. They include strung-out returning soldiers, prison inmates, former gang members, addicts, suicidal personalities of all kinds. Some of them have killed people. They have done unspeakable things but are not incorrigible. As the woman character says in Bernard Malamud’s “The Natural,” “We have two lives … the life we learn with and the life we live after that. Suffering is what brings us towards happiness.”

I don’t know if Mark Rudd will or even should be happy, but he is living a life of amends. In this book, he takes responsibility for “the destruction of SDS [as] probably the greatest single mistake of my life [and I’ve made quite a few] … a historical crime.” In speaking to young people, he can vividly describe the difference between radicalism and fanaticism, and the moral, emotional and political costs of the latter. He can confide that the best of us are capable of the worst. His wounds are gifts; he becomes a character in one of those Scared Straight performances, an important signifier for the next generation. And he continues working humbly, patiently and energetically as a rank-and-file activist.

There is a larger reason for trying to understand a Mark Rudd. He was only an inflated individual symbol of many young people around the world who took up weapons, or dreamt of taking up weapons, or went underground, or dreamt of going underground, or sheltered people underground, or dreamt of sheltering people underground, in the years between 1966 and 1975. During the same short period, less than a decade, there were more than 100 violent rebellions in American cities. Hundreds of campuses were shut down. The murders of the Kennedys and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. seemed to confirm, on a deep existential level, that peaceful change was impossible. The greatest flare-up of urban violence in America followed Dr. King’s death on April 4, 1968, two weeks before Columbia and six months before the formation of the Weathermen. It would take a contortionist to reduce this collective rebellion to Freudian categories reserved for individual diagnoses, or to forms of mass psychosis like Eric Hoffer’s notion of true believers. This massive cohort of mutinous and violent young people within the ’60s generation is little researched or remembered in mainstream culture. They were young, educated, and mostly lived in societies with civil liberties and elections.

In Latin America, other young people, struggling often in dictatorial societies, participated in at least 20 guerrilla insurgencies modeled after the Cuban revolution, inspired by writers like Regis Debray and Carlos Marighella, the same authors studied by the Weathermen. Thousands were abducted, tortured, assassinated, disappeared. Though none of the Latin American movements, with the exception of Nicaragua, succeeded militarily, theirs was the generation that directly produced or influenced many leaders of today’s successful democratic revolutions across the continent. It was revolutionaries from Mexico City’s 1968 massacre of students, for example, who went on to create the Zapatistas. In Europe, formations like the Weathermen burst out in several countries. In Germany, at the time of the Columbia student strike, radical youth protesting civic apathy toward Vietnam set fire to a Frankfurt department store, on grounds that it was better to burn it down than to run one. A well-known journalist, Ulrike Meinhoff, feeling that in her role as a columnist she was only a pressure relief valve, joined a violent underground group, was imprisoned with others and hung herself on May 8, 1976, the anniversary of the end of World War II. In its beginning phase, her Red Army Faction had the sympathy of one of every four Germans under 30, according to a 1971 survey. Her Red Army Faction, like Italy’s Red Brigades or Japan’s Red Army, was more violent by far than the Weather Underground, and would spiral into lethal destruction.

Another example is the Irish Republican Army, revived in the late 1960s, which fought a 30-year war against England before signing the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. And in Quebec, revolutionary nationalists carried out kidnappings and bombings. As with Latin America, many of the participants in these revolutionary currents evolved to hold political office or serve in prominent professions today.

To my knowledge, no one has convincingly explained how all these events took place concurrently and with little coordination, or how so many middle-class young people chose violence as a moral and political necessity. The Paris revolutionaries of May 1968, for example, sent the striking Columbia students a telegram saying, “We’ve occupied a building in your honor. What do we do now?” In Rudd’s book, he typically writes that “I don’t remember our answer.” In Derry, Northern Ireland, the slogan “Free Derry” was adopted from “Free Berkeley.”

There is a logical sequence from protest to resistance in the late 1960s. Protest assumed the authorities were listening, while resistance meant their institutions had to be disrupted, forcing them to pay a price. Resistance at first meant street battles with police, occupying buildings, burning draft cards, attempts to stop business as usual, and then gradually the beginnings of destroying property. It seems clear that the resistance escalated as the authorities chose to escalate an unpopular Vietnam War, or continue supporting dictatorships like the Shah’s in Iran, in utter disregard for public opinion, petitions and peaceful protest. People were dying every day, on television, making a moral mockery of appeals for gradual change. It is clear, however, that the moves from protest to resistance, and from there to underground revolutionary action, took place as necessary reforms were rejected by the authorities while wars like Vietnam and dictatorships like the Shah’s seemed to rage beyond democracy’s reach. For example, street violence escalated decisively in Germany after the shooting of student leader Rudi Dutschke. Perhaps the advent of a televised war, combined with repression by police and the impatient inexperience of youth, caused the rapid escalations toward violence. I often wonder whether the propensity toward violence was greatest in the Western countries or communities that suffered fascism in the previous generation, like Germany, Italy and Japan. Even in America, Rudd, who was born two years after World War II ended, grew up wondering whether he would have bowed in the face of such evil.

The sudden subsidence of this violence in the mid-1970s also points to a sociological, rather than a pathological, explanation of its nature. The end of the Vietnam War, the forced resignation of Richard Nixon from the Oval Office, the U.S. rapprochement with China, the new openings for voter participation inside the political system, all contributed to a sharp abatement of the revolutionary fevers of the 1968-73 period.

Ironically, the Justice Department dropped federal charges against Rudd and the Weather Underground for fear of revealing their undercover techniques, and in 1978 federal prosecutors actually brought charges against the FBI for their Weathermen probes. One might even say, as the rhetoricians of the Weather Underground might have put it, that white-skin privilege helped to exonerate Mark Rudd. Or, more importantly and fundamentally, to put it another way, public opinion caught up with the radicalism of the 1960s — on issues like Vietnam and Watergate — at the very moment that the revolutionaries had given up on public opinion in order to go underground.

As the research and writings of James Gilligan demonstrate, violence is more situational than innate. Violence and shame are closely connected. The acceleration to violent behavior can be breathtaking. The violence of the young signals a dysfunction of the elders, not a nihilist seed. As John F. Kennedy famously said, those who make peaceful change impossible make violent revolution inevitable.

Now we have chosen a president, Barack Obama, who has known some of the Weather Underground veterans in their later incarnations. If he had been born 20 years earlier, Obama too might have given up on community organizing and become a black militant. The question he and the rest of us face today is whether we as a nation are prepared to act rapidly and deeply enough to prevent the conditions that provoke avoidable violence in a new generation yearning for substantial change. That’s the question a reading of Rudd’s book should make us ponder.

|

Tom Hayden, a founder of Students for Democratic Society (SDS) in 1962 and principal author of “The Port Huron Statement,” is a former longtime California legislator, serving in both the state Assembly and the state Senate. He is the author of many books, including the forthcoming “The Long Sixties: From 1960 to Barack Obama,” “The Newark Rebellion,” “The Trial,” “The Love of Possession Is a Disease With Them,” “Street Wars,” “The Lost Gospel of the Earth,” “Ending the War in Iraq,” and, most recently, “Writings for a Democratic Society: The Tom Hayden Reader.” |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.