Tom Brady – His Own Worst Enemy

The sports media were among the most surprised by the recent news that a four-game suspension was back on for the football star. But given Brady’s and the Patriots’ history, it really shouldn’t have been a surprise to anyone. Jeffrey Beall / Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA)

1

2

Jeffrey Beall / Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA)

1

2

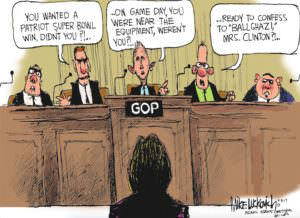

Proof is not required in such cases. As any second-year law student can tell you, many cases are decided on the basis of circumstantial evidence. A trier of fact—a person (such as a judge) or group of people (such as a jury) determining facts in a legal proceeding—decides guilt, particularly when an accused party destroys evidence relative to the case.

This, of course, is what Brady did when he destroyed his cellphone. As one of the three judges in the April 25 decision, Barrington Daniels Parker Jr., put it, “Anyone within 100 yards of this proceeding would have understood the cellphone issue. Would have understood that the cellphone issue would have raised the stakes. Mr. Brady’s explanation”—that he simply destroys his cellphones from time to time—“made no sense whatsoever.”

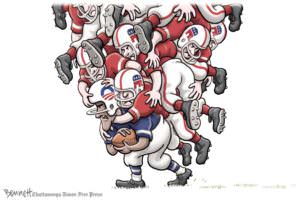

Evidently a great many people in the media who have covered this case were more than 100 yards from the issue. They did not seem to understand that Brady’s arrogant destruction of evidence was a legal issue that could only come back to blindside him.

Nor did many in the media seem to understand one very basic fact about Deflategate: It was never a fight between NFL Commissioner Goodell and the National Football League Players Association, defending Brady. It was, from Day One, a struggle between Goodell and one of his bosses, New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft.

It may seem odd to describe a team owner as the boss of a sports commissioner since we’re so used to hearing the commissioners described as the “czar” of their particular sport. But it should not be forgotten that all commissioners work under personal services contracts at the discretion of the owners who hired them.

To be sure, the union has supported Brady. Its statement after the most recent judgment was predictable: that the NFLPA was disappointed by the ruling, and that their legal counsel and his staff would “carefully review the decision, consider all of our options, and continue to fight for the players’ rights and for the integrity of the game.”

Sounds good, but realistically they all—including Brady and his attorneys—know that the next level for this case is to ask for a rehearing with the full U.S. Circuit of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit and to the Supreme Court, and it’s highly unlikely that the top court would agree to hear it.

That did not stop Brady from adding Ted Olson to his legal team on Friday, the same Ted Olson who was the U.S. solicitor general from 2001 to 2004 and represented then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush before the Supreme Court in George W. Bush v. Albert Gore, the case that decided the outcome of the 2000 presidential election.

The crux of the matter now is the basic agreement between the union and the NFL owners, in which the union agreed that the commissioner could both judge the discipline of players and also arbitrate decisions.

When Berman reversed Goodell’s ruling, he wasn’t saying that Brady was innocent or that the investigation ordered by Goodell didn’t make a sound case for Brady’s guilt. What Berman was saying was that the punishment Goodell imposed, the four-game suspension, exceeded the power given to him in the basic agreement.

It would have been interesting to see what might have happened if, the day after Berman’s ruling, Goodell simply came back and said, in effect, “Well, OK then, if I was too tough, let’s make that suspension three games or maybe two.”

Thanks to the clarity and wisdom of the 2nd Circuit Court, it is clear that Berman shouldn’t have been rendering an opinion on this case for the simple reason that every previous time a case involving sports team ownership and a sports players union has gone to court, the ruling has been (and usually in these exact words): “This is a matter for collective bargaining.”

This was the position of the Supreme Court in 1972 in the most famous sports management versus labor case of all, Curt Flood’s suit against Major League Baseball for free agency (i.e., a team could not “own” a player for life). Flood lost the case, but the baseball players union eventually won the right to free agency—not through the courts but through collective bargaining and arbitration.

The easy judgment in Deflategate would be that the NFLPA blew this case for Brady back when it foolishly granted the commissioner so much power in the basic agreement. And this clause will undoubtedly be on the table when the next labor contract is negotiated in 2021—although who knows, since that won’t be for another five years. (All parties were so satisfied with the current agreement that they made it a 10-year deal.)

But let’s acknowledge now that the problem with Brady’s case was Brady himself. Should he get in trouble in the future, maybe he won’t be arrogant enough to “destroy” his phone.

Allen Barra co-wrote “A Whole Different Ball Game, The Inside Story of the Baseball Revolution” with Marvin Miller, longtime executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association.

Your support matters…

SUPPORT TRUTHDIG

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.