To Fight the Anti-Choice Juggernaut, Documentary Builds a Barricade of Personal Experiences

"Abortion: Stories Women Tell" avoids politics, instead letting women share accounts of how they coped with governmental restrictions on the procedure. One of the women in "Abortion: Stories Women Tell." (StoriesWomenTell.com)

One of the women in "Abortion: Stories Women Tell." (StoriesWomenTell.com)

One of the women in “Abortion: Stories Women Tell.” (StoriesWomenTell.com)

In 1969, when Norma McCorvey of Texas became pregnant with her third child, she tried to get an illegal abortion at an unauthorized clinic, but it was no longer in operation.

With little choice, she decided to seek a legal abortion instead, claiming she had been raped (Texas law at the time made exceptions in cases of rape and incest), but there were no police records on the alleged incident and the claim went nowhere.

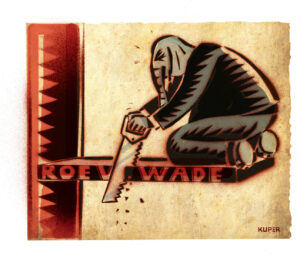

Out of options, she was referred to a pair of smart and hungry young attorneys, Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee, who filed suit on her behalf under the alias Jane Roe, against Dallas County’s then-District Attorney Henry Wade. The outcome of Roe v. Wade, a legal keepsake for decades, is now facing some of its most severe challenges.

Since the extremist victories of the 2010 midterm elections, some 288 laws inhibiting access to abortion have been passed, with 57 new constraints coming last year alone. TRAP laws (Targeted Restrictions Against Abortion Providers) are thinly veiled efforts to close down underfunded clinics by placing undue demands on doctors, facilities and patients. While proponents may argue that the laws are meant to improve service, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant called TRAP laws enacted in his state “the first step in a movement” that intends to “end abortion in Mississippi.”

One such law is at the heart of Tracy Droz Tragos‘ new documentary “Abortion: Stories Women Tell,” in limited release starting Friday and showing on HBO later this year. In Tragos’ home state of Missouri, a law mandating a three-day waiting period before an abortion was enacted in 2014, another roadblock for women who in many cases have to travel six hours or more to undergo the procedure.

“A lot of women may not realize if you’re in California or you’re in New York, where your access may not be perfect … it is still a whole lot better than places like Missouri,” said Tragos, who shot much of her film at Hope Clinic in Granite, Ill., where many women from Missouri go for abortions.

The filmmaker, speaking in an interview, added, “Part of this [film’s purpose] is shedding light on what many women in this country face. It’s a wake-up call.”

The waiting period for an abortion necessitates additional costs of room and board for many women who must take days off from work.

“By the time a patient has gone through [her] own very rigorous decision-making process to make an appointment for abortion care and walk into a facility with a support person, through protesters, many feel very offended that the state is then requiring them to think about it for three more days and come back again,” Dr. Erin King says in the documentary. “Women know they can make their own … good, well-informed decisions. They know they do not need state legislators telling them to go home and think about it again.”

The first major challenge to Roe v. Wade came in 1992 when the court ruled on Planned Parenthood v. Casey, a decision that maintained the right to abortion but connected the legal time frame with fetal viability. That decision created an opening that anti-abortion activists have been prying at ever since. They scored a major victory in 2003 with the passing of laws prohibiting second-trimester procedures, upheld by the Supreme Court in 2007.

In 2013, Texas state Sen. Wendy Davis made headlines with her 12-hour filibuster against proposed TRAP laws, which the state enacted anyway. It requires doctors performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles, as well as rigid ambulatory surgical center requirements that include things having nothing to do with women’s health care — hallway widths, shower facilities, lockers, heating and cooling conditions — the costs of which are meant to bankrupt clinics.

In the three years since those laws were passed, the new restrictions closed roughly half the state’s 41 clinics, and one study shows that between 100,000 and 240,000 women have attempted abortions on their own. Nationwide, a record 162 clinics have closed since 2011.

“I’m hoping that because we’re taking such a personal stance and women are sharing such personal stories, it is going to be harder for people to come in and shame and bully women,” said Tragos, whose film avoids politics, emphasizing personal stories instead.None is more personal than that of Dr. King, who is bullied on her way to and from work every day. Protesters call her a butcher and worse, and some even show up at her home. On particularly hard days she finds comfort in a ledger in which many of her patients have written notes to themselves, other patients and doctors:

“I am here for my family. We cannot have another child right now — it would not be fair, I cannot financially or physically have another baby.”

“You are going to be ok. You are a strong women [sic] and you know what you need in life right now. God loves you and will help you now.”

“Thank god for Hope [clinic]. I don’t know what I would do without this place. I might be dead.”

“The words in these journals are both restorative and a reminder that we are helping actual individual people,” King says. “The insight from these words helps me be a better doctor and provide better care.”

Naturally she takes exception to the personal insults she receives, but more disturbing is the mischaracterization of what she does as unsafe or shoddy work. Worse still is the way politicians have used a series of discredited videos to accuse Planned Parenthood of trafficking in body parts of the unborn.

“Many people only saw the videos as presented originally and have not really heard the follow-up and results of the countless investigations that have found the videos to be completely false and no wrongdoing on the part of Planned Parenthood,” King says. “Republican lawmakers and Republican presidential candidates’ use of the completely false information in [the videos] has led to the general acceptance of completely anti-choice language in the presidential platform and a party that is completely against abortion being legal in the future.”

Both King and Tragos take heart in the recent top court decision in the case of Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, which overturned Texas TRAP laws, neutralizing a principal weapon of anti-choice activists.

“Up until the Supreme Court ruling, clinics have had to close. They’re being threatened. Whether that will change or not, I assume that’s what’s going to happen and I hope that will happen,” Tragos said. “But Missouri is still a state, for the past two years, that has had only one provider,” she said, sighing. “We’ll just have to see.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.