Threat to Tribe, Caribou Is Averted — for Now

GOP-led proposal to allow oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge fails.

One of North America’s most high-stakes environmental battles in years appears to have come to an end in Congress — at least for now. [UPDATE: Senate Blocks Alaska Drilling]. Throughout it all, no one has had a greater stake in the outcome than a small native tribe north of the Arctic Circle.

Held in the balance has been not only one of North America’s most beautiful wilderness areas but a way of life thousands of years old.

The 5,000-member Gwich’in tribe of northwest Canada and nearby Alaska depends for its livelihood on the twice-yearly migration of caribou through its lands as the animals travel to and from their calving grounds in the Arctic refuge.

If the caribou population is markedly decreased by oil drilling, as the Gwich’in and environmentalist groups fear, the Gwich’in will lose their main source of food and a crucial part of their culture. For that reason, the tribe has been a frequent fixture in congressional lobbying, with the tribe’s leaders often traveling to Washington to join the fight against the drilling plan.

Yet for anyone who makes the journey back with the Gwich’in to their lands north of the Arctic Circle, it is clear that this debate in Congress is both vitally important and almost abstractly remote.

In April, I accompanied two Gwich’in hunters on a 220-mile hunting trip via snowmobile up the Porcupine and Bell rivers, east of the Gwich’in hamlet of Old Crow in northern Yukon Territory.

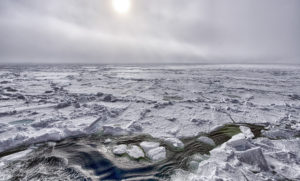

Out on the hunt, the only thing real was the vast and empty northern frontier, in which uncertainty and sheer chance are constant companions. The thin line between scarcity and plenty is harsh–an echo, perhaps, of what a new northern oil boom could bring.

Wind blew silently up the canyons one late April night, slipping along curled bluffs, across snow and ice toward distant mountains. At midnight, the glow of sunset lingered on the horizon, promising Arctic summer soon to come. But for two native hunters there was nothing but failure.

Robert Kyikavichik’s snowmobile had keeled over sideways into the slushy surface of a frozen river. The way ahead had become an impassable quagmire after a sudden thaw. And the big herd of caribou believed to be nearby was nowhere in sight.

Kyikavichik and his hunting partner, Harvey Kassi, would have to turn back toward home, 100 miles downriver in Old Crow, having failed to obtain their families’ main sustenance.

“No caribou,” said Kyikavichik. “No meat this time.”

For thousands of years, the springtime ritual of hunting caribou has been repeated. The 5,000-member Gwich’in tribe of northwest Canada and nearby Alaska has sustained itself by the sometimes generous, sometimes cruel luck of the hunt. Tribal members prosper when the animals are numerous, and they suffer hard times when the caribou are scarce.

The Gwich’in caribou hunt is a ritual nearly as old as human presence in the continent. At a site 35 miles southwest of Old Crow, a village of 310 people, Canadian archaeologists have found stone tools that they believe date from as much as 20,000 years ago–among the oldest human finds in the Western Hemisphere. That historical period coincided with the last ice age, a time when Alaska and Yukon were the only part of northern North America left uncovered by ice and when a land bridge across the Bering Straits allowed human migration from Asia.

Archaeologists say early inhabitants of the region survived by hunting caribou, woolly mammoths, bison and horses. Another archaeological dig near Old Crow unearthed a spring caribou hunting site 1,200 years old.

Modern-day Gwich’in carry out this same tradition with snowmobiles and rifles.

Kyikavichik’s and Kassi’s hunting trip began in Old Crow, which lies north of the Arctic Circle and is accessible only by air or by river, on snowmobile or canoe.

This time, the hunting party’s departure was slowed by weather that was freakishly warm for late April–sunny and in the 40s. “This must be global warming,” Kyikavichik said, frowning. “It’s too hot, dangerous.” (During this period, record highs were reported throughout the region, with Anchorage, Alaska, hitting 70 degrees.)

The hunters’ journey began in early evening as they drove east at high speed on the rutted snowmobile track across the frozen Porcupine. Scattered every few miles on the riverbanks were simple wood cabins, where Old Crow families typically spend weekends or entire months at a time hunting or simply enjoying their ancestral lifestyle “out on the land.”

The hunters stopped at one cabin about 50 miles out from town where they were met by Lydia Thomas, Kyikavichik’s grandmother. She welcomed the visitors with a slight bow and a smile, ushering them inside amid wood smoke and the smell of last fall’s dried caribou meat, hanging on a hook in the corner.

She served weak Twining’s tea in battered, flowered cups. Then she slipped into the short, clipped tones of the Gwich’in language.

Caribou? she asked. Far upriver, she was told. We will return in a couple days.

Other hunters had reported a herd of several hundred caribou on the Bell River, a traditional wintering spot in mountains to the east.

But Kyikavichik and Kassi would find after they left Thomas’ hut that this bonanza had become unreachable. As their snowmobiles sped up the Porcupine–and later the Bell, which feeds into it–they came across more and more sections where spring meltwater had seeped between river ice and snow cover to produce a quicksand-like, viscous layer. Whenever the snowmobiles skittered off the packed snow on the track, they bogged down in the slush, requiring quick, grunting excavations by knee-deep travelers.

Kyikavichik’s snowmobile finally tipped over and stuck deeper than ever, one tread spinning in the air.

The two hunters conferred, shaking their heads. “Not this time,” said Kyikavichik. “We can’t keep going. No luck.”

The decision to turn around empty-handed was a minor drama in a long, timeless saga, merely one failure amid countless hunting trips by the Gwich’in tribe across the ages. Each season, if the hunt is good, Gwich’in freezers will be full of caribou meat for months to come. If not, it is known as a hard year.

“We eat caribou because that’s what we always have eaten, and it’s what we can afford,” said Kassi. “That’s the only meat we eat.” He said he killed 15 caribou last year, giving most to other members of his extended family. Kyikavichik said he killed 14 caribou last year. Each caribou can provide as much as 300 pounds of meat.

In some years, the caribou pass near Old Crow in large numbers, while in other years few come and the main herd goes elsewhere. Each year’s migration pattern depends on weather, snowpack levels and sheer caribou instinct.

In fact, the Gwich’in do not live in the refuge; they live in forested areas to the south, spanning the international border in northeast Alaska and northern Yukon Territory.

In Old Crow, the main town in northern Yukon, only about 20 of the 310 inhabitants are white “southerners,” mainly members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police garrison and other government employees. There are tiny houses, one Anglican church, and silence broken only by revving snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles.

Few jobs are available other than those provided by the tribal government. All outside products must be flown in to the town’s gravel airstrip. Social life centers on the only store, the Northern, part of a chain that is successor to the venerable Hudson’s Bay mercantile empire and whose outlets are the anchor of every town and hamlet across the Canadian Arctic.

The Northern’s prices are as harsh as the landscape. Hamburger meat costs six Canadian dollars per pound, or about $5.10, and milk goes for the equivalent of $12 per gallon. Motor oil is $8 per quart. At a pump outside, gasoline is $4.90 a gallon. Videos are the best bargain, renting at only $5.20 to take the Gwich’in to other worlds populated by the likes of Reese Witherspoon and Vin Diesel.

Similar prices are reported in other Gwich’in villages, such as Arctic Village and Fort Yukon in Alaska, and Dawson City and Fort McPherson in Canada.

According to scientists who have spent years tracking caribou through the region’s frozen wastes and boggy tundra, there is no way to tell which side is right in the debate over oil drilling in the refuge.

“No one knows exactly how much oil will be found there, so we can’t predict for certain what the impact will be,” said David Douglas, an Alaska wildlife biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Unlike the rest of the Alaskan North Slope, which has been exhaustively explored for decades, the Arctic refuge’s underground potential is a mystery because the area has been off-limits to oil companies. Only one exploratory well has been drilled, by Chevron in the 1980s, and the company has not released the results.

Scientific knowledge of the caribou, however, is extensive.

The 120,000-head herd that uses the refuge is known as the Porcupine caribou herd because most of the animals spend winters near the Porcupine River, which crosses westward from Yukon Territory into Alaska about 200 miles south of the proposed drilling area. The herd is carefully studied because it performs the world’s most concentrated land animal migration after the wildebeest in East Africa’s Serengeti Plain–and because of longtime plans to drill for oil.

“We know more about this herd than any other caribou herd in the world, including reindeer,” said Donald Russell, research manager for the Canadian Wildlife Service in the Yukon Territory. “There have been proposals to develop [the Arctic refuge] since the 1970s, and scientists have been studying it more or less ever since.”

The highlight of this annual migration is the narrow strip of land on the north side of the Arctic refuge–especially the 2,344-square-mile zone known as the 1002 Area that would be opened to drilling.

The migration begins in the spring, as snow starts melting, when the caribou move from their wintering grounds to the narrow Arctic coast of Yukon. There, they funnel westward back across the Alaska border into the 20-mile-wide coastal plain of the Arctic refuge.

They arrive with near-clockwork precision in late May, tens of thousands of pregnant caribou cows clustering in large groupings in the coastal plain.

The most comprehensive scientific report on the subject, published in 2002 by the U.S. Geological Survey, showed that from 1983 through 2001, 43% of females calved in the 1002 Area, with nearly all the rest calving to the immediate east and south of its borders.

All the calving occurs in a one-week period from May 30 to June 6. The caribou stay in the plain from 34 to 67 days, fattening on cottongrass flowers and young willow leaves. They then begin a long, slow return southward to their wintering grounds.

Wildlife biologists describe the 1002 Area as unique among caribou calving areas in Alaska and Canada. Its vegetation provides about four times as much dietary nitrogen as that of other parts of the North Slope. Predators are few, because bears and wolves stay in the Brooks Range to the south, and breezes from the Arctic Ocean keep away the swarms of mosquitoes and biting flies that in other regions can literally drive caribou crazy.

Drilling supporters note that a smaller caribou grouping to the west, the Central Arctic herd, has flourished in recent decades despite the huge oil activity around Prudhoe Bay, at the northern end of their area. The herd increased from 6,000 animals in 1978 to 32,000. But scientists point out that the coastal plain is more than 100 miles wide in the Central herd area, far greater than the 10-to-20-mile width of the Arctic refuge plain, and thus the Central herd has been able to move to undisturbed calving areas south of Prudhoe Bay.

“The two situations are not comparable,” said Douglas.

The only years in which no calving occurred in the 1002 Area were 2000 and 2001, when unusually heavy snow cover forced the migrating caribou to calve in Yukon instead. This displacement caused an average 19% reduction in calf survival–a rate that, if continued, would cause a dramatic shrinking of the herd.

Studies have shown that caribou keep at least a 2.5-mile distance from oil rigs, roads and other infrastructure, even if drilling is suspended in the summer, as is normal elsewhere on the North Slope. If the entire 1002 Area is developed, calf survival will drop by 8% annually, thus causing a “possibly irreversible” decline in the herd, Douglas said.

However, geological surveys suggest that the section of the 1002 Area most likely to contain oil is the northwest two-fifths–which also is the section least used by the caribou. If oil development is limited to that area, the impact on the caribou will be statistically insignificant, Douglas and Russell agreed.

“The bottom line is that we don’t know what development scenario will be implemented over what regions, not only in the near future but 50 years from now, when who knows what the price of oil will be,” said Douglas.

Why the Republicans have fought so hard for the drilling plan despite the uncertain stakes is widely considered a mystery.

The spring migration started late because of the unusually early snowmelt and river ice breakup, but the herd came through the Old Crow area in full force during May. The hunt was good, and most villagers filled their freezers with meat. In the fall, however, luck once again turned cruel. The herd’s southward path from the Arctic refuge swerved westward away from Yukon into Alaska. Most Old Crow residents failed in their hunting trips. It will be a hard, long winter.

Compared to the sparsely populated boreal forests inhabited by the Gwich’in, the narrow plain in the Arctic refuge where congressional Republicans hope to allow drilling is even emptier. The only inhabitants of that area are about 150 people in Kaktovik, a village of Inupiats (also known as Eskimos) on the Arctic Ocean. The Inupiats traditionally are whale hunters, and their leaders have supported oil exploration in the refuge while opposing drilling in offshore waters because of a potential threat to the whales. Recently, however, an anti-drilling faction has emerged in Kaktovik, mainly comprising residents who say the business potential of tourism in the refuge offers a safer lifestyle than the easy money of oil drilling.

The emergence of this anti-drilling Kaktovik faction has robbed the Bush administration of a counterbalance to the Gwich’in lobbying offensive. Gwich’in tribal leaders often take part in lobbying delegations to Washington, pleading their cause to members of Congress and the media. Their bills are paid partly by the Canadian government, in an unusual effort at cross-border political lobbying.

“Drilling in the Arctic refuge would destroy the caribou and the Gwich’in,” said Joe Linklater, chief of the Vuntut Gwich’in First Nation, the tribal government for northern Yukon Territory.

The Bush administration rejects the charges. Calving “is something that we would have to be careful about, as we would regulate to make sure that the caribou are protected,” Interior Secretary Gale Norton said in March.

In Ottawa, the Canadian capital, government officials are not shy about telling Americans what not to do in Alaska.

“We oppose development of oil and gas in the Arctic refuge, and we are very disappointed with what is happening in Congress,” federal Environment Minister Stphane Dion said in a telephone interview. “We think drilling in this refuge will have a very negative impact on the Porcupine caribou herd, and on the Gwich’in First Nation who rely on caribou for food and a way of life.”

Dion rejected suggestions that Canada is interfering in U.S. politics. “The caribou have no borders,” he said. “It’s also a Canadian resource at stake. I’m sure if the situation were the other way around, with Canadian oil activity affecting Alaskan natives, the U.S. Embassy would not be shy to make public the point of view of the American administration.”

Among the Gwich’in, most people I interviewed said they had no political opinions to speak of. “The only politics that people here care about is caribou,” said Kassi.

After their failure on the Bell River, Kyikavichik and Kassi drove home faster than ever.

At Lydia Thomas’ hut, they were met with tea and a worried look. What happened to the caribou? she asked in Gwich’in.

None this time, she was told.

Will they come this year? she asked. The weather is getting stranger and stranger, she said.

We don’t know, she was told. Breakup of the river ice is coming soon.

Thomas paused, rubbing her gnarled hands.

“I am afraid,” she finally said, switching to English. “We need caribou.”

Robert Collier is a staff writer for the San Francisco Chronicle.

-

RELATED LINKS

- Senate Blocks Alaska Drilling

- House Moves to Open ANWR . . .

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: ANWR

- Norman Chance — The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: A Special Report

- ANWR.org

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.