This Gay Man Represented the President

James C. Hormel's transformation from a confused and closeted gay kid to the nation's first openly gay ambassador is chronicled in his memoir “Fit to Serve.”

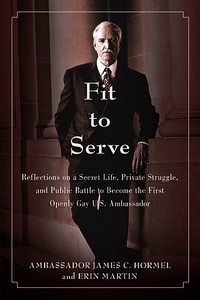

“Fit to Serve: Reflections on a Secret Life, Private Struggle, and Public Battle to Become the First Openly Gay U.S. Ambassador”

A book by Ambassador James C. Hormel and Erin Martin

James C. Hormel’s transformation from a confused and closeted gay kid to the nation’s first openly gay ambassador, chronicled in his memoir “Fit to Serve: Reflections on a Secret Life, Private Struggle, and Public Battle to Become the First Openly Gay Ambassador,” co-written with Erin Martin, is a fascinating journey into the world of privilege, politics and power. His memoir is intimate, explicit and revealing as it takes us below the surface to reveal his secret life and his public battle.

Andrew Holleran, in Harvard’s Gay and Lesbian Review, writes, “Biographies are like mummies: In exchange for permanence, the vital fluids are removed.” Fortunately, Hormel does not drain the vital fluids from “Fit to Serve.”

Hormel, an heir to the Hormel Foods fortune, may have been a child of privilege but the secret life he experienced as a young gay man is exactly like the secret life experienced by almost all young lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender people who are born into a world that neither understands nor accepts them.

Those adults who haven’t yet come to terms with their sexual orientation will see their own private struggle mirrored in Hormel’s life as a closeted gay husband, father and lawyer with political aspirations whose desire for same-sex intimacy threatened to destroy everything he held dear.

Fit to Serve: Reflections on a Secret Life, Private Struggle, and Public Battle to Become the First Openly Gay U.S. Ambassador

By James C. Hormel (Author), Erin Martin (Author)

Skyhorse Publishing, 320 pages

And Hormel’s public battle to become the U.S. ambassador to Luxembourg reveals the vicious tactics of the religious right in its ongoing war against homosexuality and homosexuals.

During Hormel’s childhood in Austin, Minn., he remembers feeling “different” from the other kids. And it wasn’t just that he was the son of Jay C. Hormel, president of Hormel Foods, or that he lived in a mansion surrounded by servants and bodyguards. “I was different for some other reason,” he writes. “As a kid I didn’t have any way of identifying the feeling and later, as a teenager, when I began to understand my ‘otherness,’ I worked very hard to avoid it. And deny it.”

During his early adolescent years at the Asheville School for Boys, Hormel remembers wanting desperately to be liked. In spite of his valiant attempts to be the best little boy in the world, he spent those formative years feeling like an outcast, never fitting in, wondering “if something was wrong with me.”

When a fellow student “cozied up” to him during a camping trip in the mountains, Hormel was “curiously excited” by the encounter but when he saw the boy the next day in class, “he would not acknowledge me.” Hormel cared more about those occasional “cozy” encounters than the other boys and he felt even more isolated and alone when “his own kind” rejected him.

Hormel flunked his first year at Princeton (an exclusive men’s college at the time). “My hormones guided me away from my studies and toward other boys,” he writes. “It is already hard for a horny teenager to focus on school, but finding that your attraction is against the rules of society adds a whole new dimension of distraction. As my sexuality bloomed, so did my feelings of insecurity and confusion.”

As an adult, Hormel writes: “I had a seething cauldron of sexual energy inside me and couldn’t keep a lid on it.” He paints a vivid picture of the double life he felt forced to live in the early 1960s. On the one hand he had a “picture perfect” married life in Chicago. He was a loving husband to his college sweetheart, a doting father to four children and a successful lawyer who was already being considered as a Republican congressional candidate. He also knew “almost instinctively” which city he could visit to find some kind of furtive sexual relief, which bar or beach or truck stop he could drop by for one of his infrequent but irresistible encounters with men.

|

To see long excerpts from “Fit to Serve” at Google Books, click here. |

“In those days,” Hormel admits, “I might have joked about faggots, or imitated a lisping, limp-wristed fellow to get a few laughs, while going out that same evening to seek an assignation with another man.” He describes the “adrenaline rush” he experienced when he knew that he was “breaking society’s mores,” at the same time living “in constant fear of discovery.”

The idea of “coming out” and dealing with the consequences was unthinkable. “No, no, I can’t do this,” he remembers saying to himself. “I cannot risk ruining my life or humiliating my entire family.” And yet as time passed Hormel became less and less able to ignore or sublimate his growing need for same-sex intimacy.

“There was no frame of reference to help me figure out what was going on inside my head and my body,” Hormel writes. “There were no resources, no role models. Even Truman Capote, as openly gay as he seemed, always appeared in public with a woman on his arm.” Eventually, Hormel’s conflict became unbearable.

Hormel’s ambivalence and anguish were not the result of cowardice or weakness. In the 1960s homosexuality was still a crime (in every state), a “sin” (in the eyes of Catholic and Protestant clergy) and a “sickness” (in the American Psychiatric Association’s “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders”). Mental and physical health professionals were prescribing drug regimens, various aversive therapies and even electric shock to help their patients overcome this “psychological illness,” and “official Washington actively hunted down and fired gay and lesbian civil servants,” Hormel remembers.

Although he lost his marriage and his chance to run for Congress, Hormel finally ended those years of ambivalence and guilt. But it wasn’t science or history or the American Psychiatric Association that led to his self-acceptance. It was falling in love with a man, discovering a new family in the gay community and becoming an activist in the gay struggle for civil rights.

As a fledgling gay activist, Hormel found himself on the front lines of the war being waged against LGBT people by the religious right. It was a battleground where his inherited wealth, which had embarrassed him early in life, was badly needed.

When Hormel realized that his money could be used “to touch people on a broad scale,” he began his public battle to win justice and equality for his LGBT sisters and brothers in the U.S. and abroad. The climax of that struggle was the fierce seven-year battle to become America’s first openly gay ambassador. Hormel knew an appointment would require Senate confirmation. “That would oblige one hundred U.S. senators — and in all likelihood, the media and the American public — to decide whether a gay person was fit to serve as a direct representative of the president of the United States,” he writes. He was going to use the political points he had accumulated as a primary donor to the Clinton campaign to fight for full acceptance for LGBT Americans.

The religious right was fanning a firestorm of protest. On Pat Robertson’s “700 Club,” Hormel was called “a radical homosexual activist” whose philanthropic work had “helped popularize homosexuality and child sex abuse.” A “700 Club” reporter described an anti-Hormel protest as “not about politics — it’s about the sexual abuse of children.” The religious right circulated false and outrageous stories that Hormel was “well known for keeping minors for sexual use.” Robertson concluded, “Your rights as the American people are being violated on this one, and to send this, this pedophile advocate to Luxembourg or any foreign country is an absolute outrage.”

In spite of the vicious attacks on Hormel from Catholic and Protestant fundamentalists, no one at the White House or in the State Department mentioned his sexual orientation, until a rumor began to circulate that Hormel might be appointed ambassador to Fiji, where homosexuality was illegal. Although the storm of protest that followed was particularly nasty, Hormel and his colleagues had a brief moment of comic relief. When an attaché from the U.S. Embassy explained to the president of Fiji that Hormel was an activist the same way Elizabeth Taylor was an activist, the president responded, “Well, then send us Elizabeth Taylor.”

Fit to Serve: Reflections on a Secret Life, Private Struggle, and Public Battle to Become the First Openly Gay U.S. Ambassador

By James C. Hormel (Author), Erin Martin (Author)

Skyhorse Publishing, 320 pages

Refusing to act on Hormel’s appointment, the 105th Congress adjourned. Hormel had just two years remaining before President Clinton left office. Then on Friday, June 4, 1999, John Podesta, the White House chief of staff, called Hormel and asked, chuckling, “You do speak French, don’t you?” “I sure do,” Hormel replied. “Well, then, bon voyage,” Podesta said. Hormel had finally won. He remembers:

“The conservative Washington Times wrote in an editorial the next day: ‘Mr. Hormel stands not as a presidential choice who happens to be homosexual, but rather as a homosexual activist who happens to be a presidential choice. As a symbol, then, Mr. Hormel transcends the less-than-world-shaking nature of his official role in tiny Luxembourg.’

That was exactly what I was after: to be a symbol of change.

The greatest irony of my long fight was that after devoting the better part of my life trying to blend in, I was willing to stand apart from the crowd.”

In 2010, Hormel, now almost 80, looked back on his 50 years of service to the gay community and celebrated the advances LGBT people had made and the struggles yet to be won:

“But the greatest mind-changers among us were the thousands of fameless people — the lesbian police officer in seaside New Jersey, the gay Wall Street banker, the gay lawyer in Oxford, Mississippi, and the transgender hairdresser in Peoria — people who lived steady, even predictable lives, true to the desires of their hearts. Whether, as a price for their honesty, they were thrown out of their father’s house, mocked at the water cooler, or subjected to kicks and punches on an unlucky, dark night, their fearlessness was persuasive. As they went to work, did their grocery shopping, mowed their lawns and paid their taxes, they showed those around them that in pretty nearly all respects, they were just like everyone else. They sent a message, which, regardless of its popularity, got through to most Americans: We’re here, and we’re not going away.”

Hormel, ironically, condemns the religious right only in its opposition to him as America’s first openly gay ambassador. That same campaign of lies, however, also created the hostile, anti-gay climate that led to Hormel’s secret life as a youth and his private struggle as a husband and father.

The anti-gay teachings of religious leaders (Catholic and Protestant alike) have poisoned minds and hearts against homosexuals for centuries. Those teachings, based on biblical misuse and scientific ignorance, are still toxic, still forcing LGBT people to live in closets of fear and self-loathing, still causing intolerance, discrimination, bullying, beatings and even death. One recent survey reveals that nearly half of those who identify with the tea party consider themselves a part of the old religious right. They believe the Bible is the literal word of God. They believe that America is a Christian nation and that public officials — local, state and federal — should pay more attention to [the Christian] religion.”

“People are still losing jobs for being gay,” Hormel writes. “People are still being killed in the meanest and most humiliating ways because of their sexual orientation and gender identity. We must focus the public on the injustice of it all and get their support to repeal DOMA [Defense of Marriage Act], pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, and change federal laws and regulations that bar same-sex partners from enjoying the medical, tax and financial benefits that heterosexual couples enjoy.

“An important question about patriotism is whether is it possible for any patriot to sit on the sidelines and not be involved. For gay people, my answer is no. We have to be out. If not, we are complicit with the old order, the one that would have us remain invisible. We have a perfect opportunity now to fight for the Respect for Marriage Act, which would repeal DOMA and open the door to full marriage equality. We must not miss this chance.”

The Rev. Mel White is co-founder of Soulforce and the author of “Stranger at the Gate: To Be Gay and Christian in America” and “Religion Gone Bad: The Hidden Dangers of the Christian Right.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.