|

To see long excerpts from “The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark” at Google Books, click here.

|

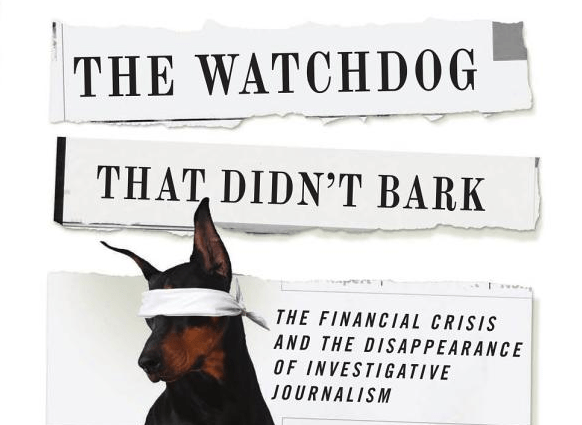

“The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism”

A book by Dean Starkman

Most American news organizations missed the two biggest stories of the previous decade: the unwarranted invasion of Iraq and the Wall Street depredations that crashed the global economy. Each caper immiserated millions, neither was especially difficult to detect, and both could have been prevented with a combination of critical reporting and basic governmental oversight. Dean Starkman’s new book, “The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism,” tackles the business press’ failure to warn of the most catastrophic financial crisis in 80 years. His analysis leaves little doubt that beat reporters were focusing on the wrong things, responding to the wrong incentives and writing the wrong kind of stories for their work to perform its watchdog role.

Starkman is no Monday-morning quarterback. Now an editor at the Columbia Journalism Review, he worked for The Wall Street Journal from 1996 to 2004, when the financial crisis was brewing. Before that, he was an investigative reporter for the Providence Journal, where he shared a Pulitzer Prize for a series on judicial corruption. For this book, Starkman reviewed the entire corpus of relevant stories from nine top business publications between 2000 and 2007. He found that the most useful investigative stories appeared in the first half of this period. After that, the major outlets churned out investor-friendly pieces while Wall Street took the global economy over a cliff.

Starkman stages his analysis deliberately. Almost half the book is a history of American business reporting and capsule biographies of its most notable practitioners, including Charles Dow, Edward Jones, Clarence Barron and B.C. Forbes. Starkman also traces the history of investigative reporting, giving pride of place to Ida Tarbell’s muckraking stories on Standard Oil during the Progressive Era. He touches lightly on other periods of intense investigative reporting, letting a few examples (e.g., The Washington Post’s Watergate stories) stand for the whole. He mentions but does not explain the fact that small outfits rake a disproportionate share of the muck. To break their stories, they often play large news organizations off one another. Glenn Greenwald’s handling of the NSA whistle-blowing story is a recent but by no means isolated example.

Along the way, Starkman introduces and historicizes a distinction between what he calls access and accountability journalism. Access reporting, which is relatively quick and easy to produce, focuses on business stories that help investors reach their financial goals. Orthodox in its assumptions about markets, it relies heavily on scoops from major players and tends to portray them positively. Accountability reporting, in contrast, may target those movers and shakers in an effort to expose mischief. Its audience isn’t investors but the public at large, and its sources are more likely to be disgruntled employees, customers or competitors. Accountability reporting is slow, expensive and risky. It often embarrasses important people and makes continued access to them difficult. Occasionally, it creates legal challenges for the news organizations that produce it. For all these reasons, accountability journalism is the first to be cut, but it’s the only kind of reporting that could have prevented the corruption and negligence that cratered the global economy.

Starkman also puts faces on these two modes of journalism. He offers Andrew Ross Sorkin, who edits the DealBook section of The New York Times, as a chief practitioner of access reporting. Sorkin, who wrote a best-selling postmortem of the financial meltdown, was delighted that so many Wall Street honchos came to his book party. One looks in vain, however, for a Sorkin piece warning about improprieties in progress. Starkman notes that Rupert Murdoch is allergic to accountability reporting, which he considers self-important and elitist. After purchasing The Wall Street Journal in 2007, Murdoch pushed for shorter pieces and more scoops based on the paper’s privileged access to newsmakers. A few years later, however, Murdoch himself was the target of investigative reporting. When The Guardian broke the phone-hacking scandal at Murdoch’s London-based tabloid, he was forced to grovel before a parliamentary committee. It concluded that he was “not a fit person to exercise the stewardship of a major international company,” and Murdoch resigned as director of News International.

Starkman credits accountability reporting by Michael Hudson, Gretchen Morgenson, Susan Faludi, Matt Taibbi and Lowell Bergman, the former “60 Minutes” producer whose work now appears on PBS’ “Frontline.” Bergman isn’t a business reporter as such, but he collaborated with New York Times reporter Diana B. Henriques to expose predatory subprime lending in 2000. Within weeks of that story’s publication, the federal government acted to curb some abuses. Starkman doesn’t attribute that response entirely to the Times story, which he writes was “part of a wider network of consumer activism and legislative and regulatory action.” Yet Starkman continually underscores the vital role such journalism plays in a healthy democracy. Starkman’s distinction between access and accountability journalism also informs the current controversy at “60 Minutes.” First broadcast by CBS in 1968, a high-water mark for muckraking, the program made its reputation by mixing hard-nosed investigative reporting with lighter fare. In recent months, however, access reporting has prevailed, even when the topics call for strict accountability. In November, Lara Logan interviewed Dylan Davies, who wrote a book about his supposed experience in Benghazi. (His publisher was a Simon & Schuster imprint headed by former GOP operative Mary Matalin.) Davies’ account was quickly discredited, “60 Minutes” pulled the piece from its CBS website, and Logan apologized on air before taking a leave of absence. Next came a Charlie Rose interview with Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and new owner of The Washington Post. Critics considered the piece a 20-minute advertisement for Amazon the night before Cyber Monday. Rose mentioned Amazon’s $600 million contract to provide computing cloud services to the CIA, but never asked whether that deal might affect the Post’s coverage of the agency. Weeks later, “60 Minutes” aired a long puff piece on the NSA’s massive intelligence-gathering operation exposed by Edward Snowden. The agency’s top brass reassured correspondent John Miller, a former employee of the FBI and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, that the operation was proper. The next day, a federal judge ruled that it was almost certainly unconstitutional. It’s worth noting that David Rhodes, president of CBS News since 2011, rose through the ranks at Murdoch’s Fox News Channel, which shills for the GOP and isn’t known for its investigative work. But Starkman’s point isn’t about partisan bias at corporate news outlets. The real shift isn’t from left to right, but rather from accountability to access.

Starkman argues that both kinds of journalism are necessary, but only one is in danger of extinction. The business world will always have its access reporting, which targets a motivated audience and is profitable to produce. But far from exposing faulty lending practices and unregulated derivatives trading, that reporting effectively masked those problems with its business-as-usual approach. Television programs were even more counterproductive. CNBC’s histrionic “Mad Money,” for example, touted stocks to personal investors right up to the moment Wall Street imploded. Meanwhile, the business model for newspapers and magazines was crumbling. Changes in technology and advertising practices led to mass layoffs and the “hamsterization” of reporters who managed to keep their jobs, which Starkman describes in an essay for Columbia Journalism Review titled “The Hamster Wheel”: “It’s motion for motion’s sake … volume without thought. It is news panic, a lack of discipline, an inability to say no.” Pressured to generate click-bait, they’ve had little choice but to embrace access reporting at the expense of investigative work.

Starkman’s experience makes him a reliable guide to this institutional landscape, but even he could widen his horizons. In its selection and emphasis, business journalism is always ideological in the broad sense: It assumes and reinforces a set of culturally constructed ideas about what’s worth doing and why. Starkman never quite addresses the implications of that insight. It seems normal to him that news organizations cover capital markets around the clock but give labor issues short shrift. Nor does he trace the problems he explores to the fact that American journalism itself is a for-profit venture. For that reason, we see a lot about Rihanna’s two-piece and rather less about political repression in Egypt.

Starkman laments the decline in investigative reporting, but he doesn’t propose an alternative to the way we fund it. Economists maintain that political journalism is a public good (like education, national security and law enforcement) and should be funded as such. Media historians tell us that such journalism has always been subsidized, in one way or another, both here and elsewhere. Yet more than any other industrial democracy, the United States leaves journalism to the vagaries of the marketplace. Instead of following the lead of the publicly supported BBC, for example, we continue to search, almost certainly in vain, for political journalism’s elusive new business model.

These cavils aside, Starkman has made an important contribution to our understanding of America’s media ecology. There’s more work to do, starting with the journalists themselves. Felix Salmon, a financial blogger at Reuters, has defended the business press’ failure to warn the public of the financial meltdown. “There’s a reason why these things only come out after crashes,” Salmon said in 2012. “If you do the journalism beforehand, nobody cares.” Besides, he added, most people don’t read business journalism. “If you want public-interest journalism, if you want to interest the public, you don’t want to put it in the business section,” Salmon said. “The business section is the first section that they throw away.” Perhaps Salmon is right that the business press should remain a watchdog-free zone. If so, Dean Starkman’s work can be safely ignored.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.