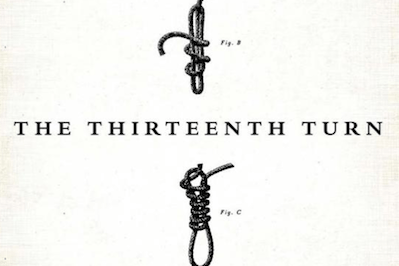

The Thirteenth Turn

“The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose” explores the little known history and symbolism of the noose and the role it played in crime, punishment and race in American society. Image by PublicAffairs

Image by PublicAffairs

Image by PublicAffairs

|

To see long excerpts from “The Thirteenth Turn” at Google Books, click here. |

“The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose” A book by Jack Shuler

My earliest memory of a noose and hangings was during Halloween. Neighbors would decorate their homes with zombies, skeletons and ghouls dangling from tree branches in their front yards.

It wasn’t until I watched the miniseries “Roots” that I learned how a noose was used to kill other humans as we discussed the show, slavery and lynchings in school. It was the scenes of nonstop whippings that made me run into the other room and cover my ears. I was unable to comprehend how people could treat one another in such inhumane ways.

Nowadays millennials and the post-9/11 generation are just a click away from a barrage of barbaric torture scenes, be it in horror movies or heinous images of dead babies and beheadings in the Middle East. I wonder how desensitized they are to such horrific violence.

Yet there was a time during the Middle Ages when swift decapitation by the sword was considered an honorable death, and prolonged hangings were an ignoble way to die.

“The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose” by Jack Shuler explores the little known history and symbolism of the noose, and the role it played in crime, punishment and race in American society. The title refers to the number of intricate twists necessary to transform a slipknot into a weapon of death.

Shuler’s narrative is framed by his in-depth reportage of significant lynchings, spanning from the Iron Age through the Revolutionary and Civil wars, to the early 20th century and the modern era with the hanging execution of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

Part of the first chapter is devoted to the technical aspects of knot making. Shuler visits a member of the International Guild of Knot Tyers who schools him in the fine but dying art of knot tying, and the patience and skill required to create a noose.

Many hangings were spur-of-the moment lynchings by angry mobs, roused by perceived injustice or hatred. A hangman’s knot was hastily crafted with whatever material was handy (twine, hemp or even chains) and tied to the nearest tree or light pole. In several cases, victims were dragged out of jail, brutally beaten, burned with torches, or shot before their corpses were left swinging in the wind.

“Hanging is crude, rough and wanton, the purpose of which is to tear apart the spine,” Shuler writes. “The body becomes a crude figure, eyes bug out, tongues protrude and necks stretch … their face contorting, body jerking and bowels evacuating.”

Shuler includes fascinating tales from the history of the hanged. The Tollund Man, the mummified corpse of a man (circa 4th century B.C.) discovered in a Danish bog in 1950, was found in well-preserved condition, with organs intact and a serene look on his face. A leather rope fashioned into a noose was still around his neck. At the Museum Silkeborg in Denmark, Shuler meets with an archeologist who explains that because other preserved bodies have been found in bogs, which were considered sacred space, the hangings were likely a ritual sacrifice or an offering to the God Odin. This explains their pristine condition.

The perception of hangings is inevitably linked to Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus then committed suicide by hanging. Judas died the ignominious death of a coward. Christ’s crucifixion, commonly juxtaposed in art with Judas’ disgraced limp body in the background, was a heroic and noble death.

Fourth-century writer Pacatus wrote that hanging “is a feminine death, unworthy of a man. … They were not supposed to dangle from a rope, they were to throw themselves onto their swords.”

Around the 4th century Emperor Constantine banned crucifixions, and hangings grew more common. Executions became a public spectacle intended to unite the community with religious fervor and reinforce the power of government. Villagers turned out in droves.

This contemptible tradition was carried over to the New World. In 1753 a young woman was hanged in Connecticut for the murder of her child in front of 10,000 onlookers. The prevalence of slave revolts in pre-revolutionary New York forced officials to move hangings to the inner harbor islands to accommodate the masses.

The culture associated with public hangings more closely resembled a carnival atmosphere than a religious assembly or community gathering. Notices and information about the condemned were well publicized, and music, dancing, food and drink were to be had. Relic hunters would scour the aftermath for pieces of rope, wood splinters from the gallows or strands of hair. Many believed these items had magical powers.

New York’s first slave revolt in 1712 lead to the Conspiracy of 1741, which resulted in the mass hangings of 34 men. The violent history of Lower Manhattan is detailed in Shuler’s walking tour, included in the book. Dead bodies once swayed from gallows on the same ground as modern day landmarks and buildings such as Zuccotti and City Hall parks. The vulgar display of bodies and heads on stakes failed to suppress rebellions. In 1776, Nathan Hale, a soldier and spy during the Revolutionary War, was hanged near present-day United Nations headquarters.The 50-foot granite sculpture Triumph of the Human Spirit in New York’s Thomas Paine Park is located on the site of a Colonial-era, African-American burial ground. Within walking distance is Ground Zero, a reminder of the evolving and deplorable ways in which humans conceive of violent mass deaths.

During America’s Age of Enlightenment, the literacy rate rose and the number of capital offenses dropped, which lead to conversations about penitentiaries, the banning of public executions, and the concept of human rights.

The well-known hanging of abolitionist and insurrectionist John Brown serves as an example of a “noble death,” as Brown calmly accepted his fate as a martyr, “hasten[ing] the extinction of slavery.”

Perhaps the most recognized hanging in popular culture is the 1930 lynching of Abram Smith and Thomas Shipp in Marion, Ind. The gruesome black and white photo of the incident was the first to be widely distributed around the country. The unaffected faces of the people in the crowd appear as if they were loitering around a Friday night football game. Appalled and inspired, a Jewish high school teacher wrote the protest song “Strange Fruit,” later recorded by Billie Holiday. Jazz singer Nina Simone, who lived five miles from where the innocent Dick Wofford was beaten and hung by an angry mob in 1894, remade her haunting rendition in 1965.

Interwoven with the numerous lynching tales are Shuler’s grief-tourist visits to execution sites. This is where he veers off course. Flowery descriptions of small town USA and random trivialities feel more like a travel journal. Snippets of inner dialogue and turmoil only distract from an already captivating discourse.

A heated exchange with a tribal historian on a reservation in Flandreau, S.D., does provide fresh insight from the Native American perspective. The bloody U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 ended in the mass hanging of 38 Dakota men. Pardoned by President Lincoln, a man named Caske was mistakenly hung with the others. The noose used to hang him is part of the archives at the Minnesota Historical Society, but the Dakota community refuses to let it be displayed. Even Shuler was denied access to the culturally sensitive material. The spirit of the executed is believed to be interconnected to the noose. Until it is destroyed, the Dakota community remains unsettled.

“The Thirteenth Turn” is a comprehensive, remarkable and necessary examination of our country’s ugly past and enforcement of capital punishment. The symbol of the noose has long been used to oppress certain groups or threaten harm if they don’t behave in a particular way. Shuler’s inclusion of several instances of nooses left on doors, hanging in the newly built One World Trade Center, and from trees on school campuses raises the questions: How much have humans really evolved? Have we learned anything from our past, or are we doomed to ride a merry-go-round of continuous conflicts and gruesome killings, steeped in racial and religious differences?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.