The Teaching Brain

This book asks the questions at the root of education: What is teaching? How does it take place? What is the process? And the question at the heart of the matter: How does teaching differ from learning?

The New Press

“The Teaching Brain: The Evolutionary Trait at the Heart of Education” A book by Vanessa Rodriguez with Michelle Fitzpatrick

The American public, for the past 10 years at least, has been besieged by endless reports in all mediums about legions of bad teachers mis-educating or under-educating the nation’s children and sabotaging America’s future in the new global economy. Most, if not all, of these reports are based on the views of non-educator “reformers.” Most are multimillionaires and several are billionaires. They are all ideologically rather than pedagogically driven. They all find the answers to problems of education in the magic of the free market. Diane Ravitch has dubbed them “The Billionaire Boys’ Club,” but with Oprah Winfrey and a couple of the Walton daughters elbowing their way into the party, it’s time, perhaps, for a new, more inclusive name like, say, The Overlords. Theirs are the voices that have utterly dominated education policies in America for a decade at least, with no sign of letting up.

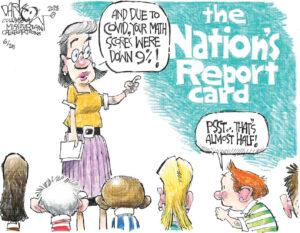

These reformers never bother to define what teaching is and what teachers actually do. Incredibly, they simply do not talk about the issue, concentrating instead on raising expectations and implementing magical standards and the like. The nearest thing I’ve ever seen regarding what the reformers believe occurs in a classroom can be seen in a cartoon clip in the much ballyhooed charter school propaganda film “Waiting For Superman”: A cartoon teacher lifts the conveniently placed lids on the heads of cartoon students and pours knowledge or information or data — whatever it is the reformers think teachers are depriving kids of — directly and effortlessly into the students’ brains. That’s as far as I’ve seen or read or heard of the reformer idea of teaching. Instead, the reformers have used their limitless fortunes to circumvent the discussion of what teaching is and what teachers do by focusing, reductio ad absurdum, almost exclusively on the results of standardized test scores. Good teaching leads to high test scores. Bad teaching is revealed in low test scores. That, for the reformers, is the beginning and the end of teaching. What else is there to talk about?

Given all this, it is more than refreshing to read a work by a veteran educator who happens also to be a researcher and sets out not merely to ask the question of what teaching is and what teachers do, but to discuss it within a radically human paradigm that is based as much on neuroscience as it is on educational theorists like Piaget and Dewey. “The Teaching Brain: An Evolutionary Trait at the Heart of Education,” by Vanessa Rodriguez with Michelle Fitzpatrick, is an ambitious work that covers an extraordinary amount of ground in little more than 200 pages. It dares to ask the simple questions at the root of education: What is teaching? How does it take place? What is the process? And the question at the heart of the matter: How does teaching differ from learning?

“[D]espite mountains of books and research on pedagogy,” Rodriguez and Fitzpatrick write, “no one has ever truly bothered to understand specifically how the teaching process and its corollary, the teaching brain, are separate and distinct from the learning process and the learning brain.”

Rodriguez and Fitzpatrick take dead aim at the “unidirectional focus” and “one way street” of “student centered” pedagogy that has saturated the country and that they find “incomplete. Everyone suffers when only the interests of the students seem to matter. Half of the equation is lost.”

The half of the equation that is lost, the authors write, is what they call the teaching brain. Rodriguez refuses to bow before the altar of reformer propaganda that insists teaching must be a selfless act and that teachers should be nothing less than missionaries for children, as if any self-worth detracts from “being in it for the kids.” This, to the authors, is nonsense.

It is also music to many a teacher’s ears.

What, for Rodriguez and Fitzpatrick, is teaching?

Teaching is nothing less and nothing more than a “human, evolutionary skill.” Their arguments are at times jolting:

“To be blunt, our current models of teaching are outdated and unsophisticated. Their deterministic and rigid criteria stand in the way of fully integrating current research from the learning sciences and what we know of how the brain works. As counterintuitive as it may seem, there is quite a bit of evidence that we have structured our system of education on animal behavior experiments, utilizing definitions of how animals teach.”

Therein are words guaranteed to get a teacher’s attention.

The authors take square aim at teaching models derived from B.F. Skinner’s behaviorism and all “animal rooted ideas about teaching formed in the 1960s,” as well as the current fads of “distance learning” in which students sit at computers listening to a “teacher” through a computer screen.

In their stead, Rodriguez and Fitzpatrick believe that teaching is an innately human, evolutionary skill available to all of us, but a skill that one must become conscious of to improve and master. One component of such consciousness emerged from the cognitive psychology work of David Premack and Sidney Strauss, who wrote that teachers, like all humans, “demonstrate a theory of mind (ToM) which refers to a person’s ability to understand what is going on in the mind of another human,” which they hold to be a necessary characteristic of human teaching.Working from ToM, the authors derive what they call a “new foundation of teaching”:

“Teaching is a process: It is an interaction that occurs between humans who express a desire to connect with each other and join their knowledge. Both people benefit from the collective knowledge and the interchange, and this kind of interaction can and does happen everywhere: within and without classrooms, with or without formally trained teachers.

Teaching is a natural human act: Teaching is a uniquely human endeavor that we employ when we want to join together and become of one mind.”

These ideas are, to my mind, profoundly beautiful and true. “The Teaching Brain” is filled with such beauty. The problem is in implementing such thinking across a school system that is now firmly in the hands of people who hold such ideas in total contempt.

Even as Rodriguez and Fitzpatrick are aware of many of the policies and programs that reformers have succeeded in implementing — Teach For America, Value Added Measures, the Common Core, charter schools, to name a few — my sense is that, like most who have not been in a classroom in a while, they have no idea of the relentlessness of the assaults nor the scrutiny that is part and parcel of the new pedagogical prescriptions. In short, they have no idea of the damage to the central nervous system of the average American teacher who, demoralized and depleted, has worked the last few years in constant survival mode.

The lessons from “The Teaching Brain” demand self-reflection and self-awareness. These things are hard to achieve in the best of circumstances, never mind for people in a permanent state of induced crisis. As much as I’d love to see ideas from “The Teaching Brain” incorporated into American pedagogy, they require a level of psychological health and stability rare in any profession at any time, but that much more so in a teaching profession under siege. Under today’s working conditions, it is hard for me to imagine many teachers having the psychological resources needed to practice and integrate Rodriguez and Fitzpatrick’s ideas, valuable though they may be. And that is a tragedy.

Perhaps, in time, that will change. Meanwhile, “The Teaching Brain” is a work that every teacher in America can benefit from reading. Part research, part theory, part manifesto, part self-help, part survey, and filled with vignettes of interaction with students, “The Teaching Brain” is a structural curiosity that somehow works, largely because, despite all the academics, Rodriguez is a teacher who never loses sight of teaching.

Whether you agree with the authors’ conclusions or not, it’s hard to imagine any teacher reading this work without being forced to rethink or confront his or her own preconceived notions. That, in any profession, is always a good and healthy, if difficult, exercise.

Patrick Walsh teaches in a public school in Harlem in New York City. He is also a chapter leader for the United Federation of Teachers and a musician. He blogs here.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.