The Story of Autism

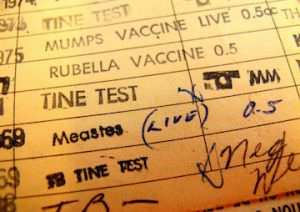

From midcentury institutions where children deemed feebleminded were committed to live in dark corners covered with their own excrement, to the millennial vaccine mania that corrupted autism research and set health policy back years, a new book paints the story of autism in sweeping, cinematic bursts.

“In a Different Key: The Story of Autism” A book by John Donvan and Caren Zucker To see long excerpts from “In a Different Key” at Google Books, click here.

I was on Page 86 of John Donvan and Caren Zucker’s magnificent opus, “In a Different Key: The Story of Autism,” when I began casting the movie.

This is when the gentle, spry Leo Kanner — a psychiatrist who first used the word “autism” to describe the childhood disorder in 1943 — turns on the mother he’s been encouraging and mentoring to care for her odd and special child.

Up until this point, Kanner had a close relationship with Mary Triplett, whose son Donald’s story bookends “In a Different Key.” Donald was autism’s “Case 1,” so Mary’s information was critical to Kanner’s research. In letters, the doctor assured her that she was an excellent mother, admirable and capable, and that Donald’s peculiarities were not her fault.

But in 1949, Kanner recanted all of it, writing a major article about the “coldness,” “obsessiveness” and “maternal lack of genuine warmth” he’d observed in the vast majority of mothers of autistic children — including Mary Triplett. “Refrigerator mothers” is the term he used to describe them.

Why would he do such a cruel thing? The answer, according to Zucker and Donvan, is ambition. Kanner (who should be played by Ben Kingsley) seized on a darkly provocative theory — also espoused by Bruno Bettelheim — because it elevated his work. When Kanner could offer no scientific explanation for autism, he got little attention and respect. But finding a witch to burn set fire to his career.

Kanner’s betrayal is the centerpiece of this spellbinding book — a universal fable about greed, power and betrayal told through the lens of autism.

Don’t worry that I’ve ruined the drama. “In a Different Key” is chock-full of suspense and hairpin turns. This is a story of violence, avarice, politics and valor. From mid-century institutions where children deemed feebleminded were committed to live in dark corners covered with their own excrement to the millennial vaccine mania that corrupted autism research and set health policy back years, Donvan and Zucker paint the story in sweeping, cinematic bursts.

In one riveting section, for instance, they tell the story of 16-year-old Betsy Wheaton, who became a lightning rod in the debate over facilitated communication (FC), a technique in which a nonverbal individual communicates by typing on a keyboard or pointing at letters, images or other symbols. In 1993, using this method with the help of a facilitator named Janyce Boynton, Betsy revealed a terrible secret: “The words spelled out by Betsy’s pointing finger turned decidedly dark and lurid. It started with curse words and a few relatively benign complaints about her father. Then, a few sessions later, in blunt and harsh language, explicit references to Betsy’s father emerged.” The girl’s family splintered following these revelations. But later experiments cast doubt on them, suggesting that Boynton had unwittingly created the story and guided Betsy to spell it out (Boynton eventually apologized to the family). Some years later, Betsy’s brother committed suicide after killing his wife; he was “never the same” after the family’s temporary breakup, Donvan and Zucker report.

Donvan and Zucker, both television journalists, have not only a flair for drama but also a sense of history. Hitler’s Germany, in particular, plays a crucial role in their narrative. There’s Kanner, a lucky Jew who left Europe before the war started; Bettelheim, a survivor of Dachau and Buchenwald, with a big Bernie Madoff personality and equally sinister flaws; and Hans Asperger, the German researcher who developed his theory of autism nearly simultaneously with Kanner’s but may have been a Nazi collaborator, studying disabled children before sending them off to be euthanized. (It’s worth noting that these are very different characterizations from those presented in Steve Silberman’s “NeuroTribes,” a similar epic about autism published last year.)And there are crucial omissions in this far-reaching book. Despite a nearly 80-page section on Ivar Lovaas and his breakthrough behavioral approach (called ABA) for children with autism, Donvan and Zucker fail to mention that Lovaas used the same sort of psychological conditioning to “normalize” young boys suspected of being gay or transgender. Nor do they acknowledge the predatory cottage industry that sprung up among parents, selling the ABA services they claimed had “cured” their own kids.

In fact, parents get very loving, Hallmark television treatment from the two authors (one of whom has an autistic child). The only families who come under fire are the anti-vaxxers, along with researcher Andrew Wakefield, whose vaccine studies — later discredited as fraudulent — unleashed epidemic disease.

Truth is mutable. Writers take a perspective that is influenced by their place and time. Much as I think Donvan and Zucker tried to be objective, “In a Different Key” reads not like a history but a story (hence, the subtitle), with drama and narrative, heroes and villains, a beginning, middle and end.

But listen: This is precisely the magic of Donvan and Zucker’s extraordinary book. Because a story can lift and inspire and center you. It delivers meaning, illuminating truth in a way that lists and quotes never could.

I have been the mother of an autistic son since 1988. I was 21 when he was born; I have grown up with him, surviving through a quarter-century of autism’s history. So I came to “In a Different Key” braced for a tedious lecture. Who were these authors to tell me about autism?

Yet this book does what no other on autism has done: capture all the slippery, bewildering and deceptive aspects. Finally, so much that had happened to my family made sense: The six different diagnoses my son received as a child, not because he was changing but because the diagnostic criteria were. The whipsaw of trends and therapies such that I felt I was never doing enough or getting it right. The famous expert who was cold and accusatory when I called him because he was embroiled in a battle between warring factions. The older relative who took one look at my mute, rocking 3-year-old and said curtly, “You have ruined that beautiful child.”

One of the most compelling threads in this book is the argument that autism has not suddenly appeared or surged. People with autism have been with us for centuries. They were regarded as fools or holy men; they were wild vagabonds; they were beaten and killed. Until the late ’70s — just a decade before my son was born — they were routinely institutionalized, especially in wealthy or educated families. It is only now that autism is out in the open that we see it everywhere.

I wept and laughed and raged while reading “In a Different Key,” all the while thinking, Yes! This is my experience, including the raw and dirty parts, but also the wonder and joy. It’s the bones of a screenplay about what it’s like to be human in this particular, vulnerable way. More important, this is my son’s story, his whole strange, endearing clan brought to life with dignity and affection on the page.

Ann Bauer is the author, most recently, of the novel “Forgiveness 4 You.”

©2016, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.