‘The Social Network’: Your Life in Pixels

The 1970s were branded the “Me Decade” long ago, but whatever shadowy committee makes such important temporal pronouncements might want to reconsider that call in light of the last 10 years.Stripped of its particulars, "The Social Network" is a classic fable about love and betrayal and the outsider wanting in so badly he ends up destroying what he desires the most.

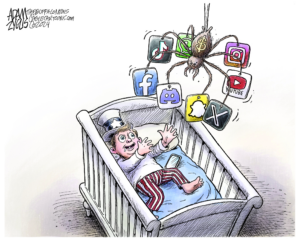

The 1970s were branded the “Me Decade” long ago, but whatever shadowy committee makes such important temporal pronouncements might want to reconsider that call in light of the last 10 years. Even the most cursory survey of the favorite pastimes, entertainment products and guilty pleasures of “the Naughts” adds up to a study of unfettered (and commodified) narcissism, at once the fodder and the inevitable byproduct of a generation spoon-fed “reality” from every lit screen and given to frequent fits of cyber-disclosure, their lives uploaded and exposed from the biggest revelation down to the grittiest pixel.

Another reviewer of “The Social Network,” David Fincher’s new film about the making of the time-sucking vortex that is Facebook, enthusiastically crowed — or tweeted, fittingly — “It’s the movie of the year that also brilliantly defines the decade.” Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers is laying it on a bit thick there, as the film falls short of its own outsized ambitions, but he’s onto something when it comes to “The Social Network’s” dominant theme and mood. Call it anomie for the digital age — the interpersonal whiplash that we’ve all no doubt felt, largely thanks to Facebook, when we’ve “liked” and “shared” more moments online than off, and been in electronic contact with more fervor and frequency than face to face, our fingers all the while only really touching our own keyboards, if you will.

By now, most readers inclined to investigate this far have probably gathered that “The Social Network” tells the origin story, maybe a fictional version, of Facebook mastermind Mark “I’m CEO, Bitch” Zuckerberg and his astounding ascendance from social-misfit computer whiz at Harvard to social-misfit billionaire — the youngest billionaire, the film reminds us, in the history of the hyper-rich. However, as Rashida Jones’ empathic rookie attorney Marylin Delpy puts it, “every creation myth needs a devil,” and Zuckerberg, played with a fascinating, simmering kind of kinetic restraint by Jesse Eisenberg, initially seems to be this tale’s top candidate to wear the horns.

However, screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s a lot smarter than that, and he has been known to draw even his least heroic characters in less blatantly infernal tones. Granted, Sorkin’s mythical Zuckerberg is clearly not someone skilled at making real friends, and he sells out, buys out and potentially steals from just about everyone whose orbit crosses his own at some point in the film. It’s no mistake that the plot intercuts scenes showing the hatching of Facebook, featuring Zuckerberg, his “only friend” and business partner Eduardo Saverin (the unforgettable Andrew Garfield, by far the film’s standout, flashing rare and raw emotion through his eyes), and a host of fellow nerd geniuses and the women whom they’d love to love them had they the game or the money or both, with later scenes in which Saverin is suing Zuckerberg for ruining both their friendship and Saverin’s slice of the company in one fatal, stock-diluting swindle.

But here we are looking at a highly unusual case involving big brains, bigger aspirations and amounts of money that would boggle even the most expensively trained minds at the elite Harvard social clubs with which dorky sophomore Zuckerberg is obsessed but to which he is not granted entry. (That’s fine — he’ll just blast his way in through a computer screen.) The film certainly invites judgment about Zuckerberg’s character, especially by explicitly depicting him all “lawyered up” in various face-offs with former partners. And although Zuckerberg’s real-life contribution of $100 million to the Newark public school system within days of the film’s release would appear to signal his own nervousness about moviegoers’ opinions about him, it never comes close to a simple verdict.

That’s partly because that’s really not the point of “The Social Network.” Stripped of its particulars, this is a classic fable about love and betrayal and the outsider wanting in so badly he ends up destroying what he desires the most. The core romance happens between Zuckerberg and Saverin, who take their relationship status, translated for the Naught (Naughty?) set, from “bromance” to “it’s complicated” to “it’s litigious” over the course of the movie. And it’s only fitting that if Facebook is where all good relationships go to die, then the creation myth of Facebook itself should also involve a few key casualties, beginning with the formative death of the highly unromantic dating interaction between Zuckerberg and the object of his erotic attentions, Erica Albright (gamely played by rising starlet Rooney Mara) and eventually endangering Zuckerberg’s standing with Saverin, the snob-jock Winklevoss twins (handled with hunky aplomb by solo actor Armie Hammer) and Napster founder-turned-professional-d-bag Sean Parker (OMG JT!!!), among others.

Ultimately, “The Social Network” is also about too much staggering success too fast and too soon, and since many in the Facebook generation apparently struggle to process life without the aid of either a gadget or a pop-cultural reference, here’s one of the latter: As Cyndi Lauper sang in a (cover) single she released in 1984, the year Mark Zuckerberg was born and back when MTV carried music videos rather than reality shows, money changes everything. It changes Zuckerberg and his team, too — and who can blame them? These are kids who can’t even binge-drink without the help of technology, and whose communication is overwhelmingly mediated — in this case, by social media, computers and/or legal representatives — to the degree that any direct expression is startling and always fleeting. And although Sorkin and Fincher make a sophisticated show of a saga that gestures at bigger ideas than the film is able to access, what shows up in the eyes and on the faces of Eisenberg and Garfield sustains the movie’s life and keeps the plot from imploding into a sleek heap of zeroes and ones without real connective tissue. But that’s the risk we run by meeting more often through screens than in our own skins.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.