The Reinvention of Malcolm X

Malcolm X's life has inspired filmmakers, writers, painters, rappers and dramatists, yet much about his murder has remained a mystery Now we have Manning Marable's "Malcolm X," a groundbreaking piece of work .

This review is from a syndication service of The Washington Post.

Malcolm Little had a tragic childhood. His father, Earl, died in 1931 in a streetcar mishap that was quite possibly racially motivated. In 1939, when young Malcolm was 14, his mother, Louise, was taken away and confined to a mental hospital. The boy soon found himself in a foster home.

By the time he relocated to Massachusetts in 1941, his jagged spiral had begun. For several years he roamed, wolf-like, between Detroit, Washington, Harlem and Boston. His activities varied: selling dope, pimping, breaking into homes, hawking snacks on trains. In 1946, the doors of the Charlestown State Prison in Massachusetts clanged behind him, putting an end to the foolishness. He would remain there for six years.

The reinvention of Malcolm Little — soon to become Malcolm X — began behind bars. “I don’t think anybody ever got more out of going to prison than I did,” he would later say. Shortly after being freed, he became a rising star in the Nation of Islam, sent by its leader, Elijah Muhammad, up and down the East Coast to open mosques. Malcolm imbued blacks with pride and offered an ultimatum to white America: Either “the ballot or the bullet” would transform American injustice. After hearing him, many blacks, fed up with living under the American system of apartheid, joined the Nation.

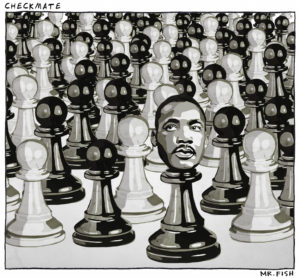

But Malcolm X uncovered proof that Muhammad had impregnated at least half a dozen young Muslim women. Malcolm’s decision to confront him set in motion their inevitable and dangerous split. Nation of Islam members believed that Malcolm had been usurping Muhammad’s popularity and plotting his own rise; Muhammad believed that Malcolm was cozying up to mainstream civil rights leaders. Malcolm’s celebrated visit to Mecca, which forced him to rethink his separatist leanings, further antagonized many Nation members. He had embarked on the path that led to his murder by Nation of Islam members on Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom, just outside Harlem.

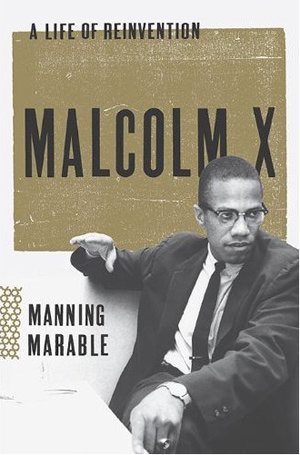

Malcolm X’s life has inspired filmmakers, writers, painters, rappers and dramatists, yet much about his murder has remained a mystery. Now we have Manning Marable’s “Malcolm X,” a groundbreaking piece of work. Marable, a historian who died on the eve of this book’s publication, convinced people who had been silent for decades to sit for interviews. He also drew upon oral histories, dusty police reports, and FBI and CIA documents. The result is not just a biography, but also a history of Muslims in America and a sweeping account of one man’s transformation — and of the conspiracy, abetted by police inattention, that took his tumultuous life. The tension toward the book’s end, when Malcolm is trying to figure out who might murder him, is so gripping it nearly soaks through the pages.

Toward the end, many Nation of Islam members had ceased calling him “Brother Malcolm”; Malcolm X was now a “heretic.” His house in Queens was firebombed, an event that Marable re-creates with chilling effect. His murder was plotted — though not with the approval of Muhammad, Marable points out — a year in advance. Marable examines the evidence against a number of suspects and abettors, including informers, inefficient NYPD officials and the murderers themselves. This is tragic and shocking material: Some of the killers apparently remain at large, while two of the convicted may have been innocent.

It will be difficult for anyone to better this book. It’s deeper and richer than a mere homage to Malcolm X. It is a work of art, a feast that combines genres skillfully: biography, true crime, political commentary. It gives us Malcolm X in full gallop, a man who died for his belief in freedom, a man whom Marable calls the “fountainhead” of the black power movement in America.

Wil Haygood, a Washington Post reporter, has written biographies of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Sammy Davis Jr. and, most recently, Sugar Ray Robinson.

(c) 2011, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.