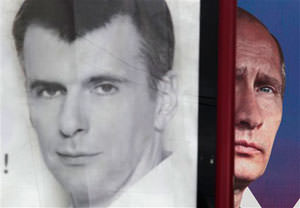

The Puzzling Presidential Candidacy of Mikhail Prokhorov

Representing oligarchs, playboys and the NBA, the billionaire is an unlikely candidate for president, but his and other campaigns may manage to embarrass Russia's most powerful man.The billionaire is an unlikely candidate for president, but his and other campaigns may manage to embarrass Russia's most powerful man.

Crowds in Moscow and St. Petersburg are still protesting against the irregularities of the Dec. 4 Duma elections. Russia’s political establishment, for its part, is turning its eye to the presidential elections of March 4. The candidacy of billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov in particular has caught the attention of political analysts and media outlets in Russia and abroad.

Prokhorov announced his candidacy in the wake of the Moscow protest on Dec. 10. He has presented himself as a “consolidator” of the liberal opposition, a capable candidate who could challenge Vladimir Putin. Referring to blogger and political activist Alexei Navalny’s popular characterization of the ruling party United Russia, Prokhorov said: “I am no swindler and no thief. I am a manager!”

The 46-year-old Prokhorov, with assets estimated at $18 billion, making him the third-richest man in Russia, is an unlikely candidate for president. He has a reputation for being a playboy and owns a 300-foot yacht, at least two custom-made private planes and the New Jersey Nets NBA team. In 2007, French police arrested him on suspicion of running a prostitution ring. He claimed that the women were just students and models, and the charges were dropped.

As one can imagine, “oligarchs” like Prokhorov are very unpopular in Russia. Their escapades fill tabloid magazines and their lifestyle is so radically different from those of other Russians that they might as well live on a different planet. The collapse of the Soviet Union — the reason for the impoverishment of the vast majority of Russians — made those with the right connections and business savvy extremely wealthy.

This was no different for Prokhorov. He made use of the economic opportunities that opened up during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika. He joined the Communist Party at a time when it was no longer a necessity — “purely for career reasons,” as he recently admitted in an interview with the Russian magazine Itogi. At the same time, he was a successful early Soviet businessman, earning his first car by dealing in jeans. He began working at the Soviet International Bank for Economic Cooperation in 1989 and made contacts with those actors in the Soviet government who would lead the transformation to a market economy merely two years later.

He also met Vladimir Potanin, today Russia’s richest man and a deputy prime minister responsible for the privatization of the state-run economy in the 1990s. The two founded one of the first private banks in Russia and began luring customers away from state banks. Within six months, they had accumulated capital equivalent to $300 million.

The early 1990s were a time of great opportunity for any Russian businessman with money. Soviet corporations were being privatized and, within the country, very little capital was available. Had the Boris Yeltsin government sold state corporations at their market value, Western companies would have inevitably bought them. Hence government officials sold them for a fraction of their real value to Russian businessmen they considered to be loyal. Whoever managed to make it into this select circle was guaranteed to become very, very rich.

Potanin and Prokhorov bought the company Norilsk Nickel for $170 million. This made them billionaires overnight. In 2007, the company was worth $60 billion. The economic and financial crisis in Russia in 2008, in which fears of the political fallout of the war against Georgia and a plunge in oil prices led to a crash of the stock market, cut this value in half. Prokhorov, however, sold his shares in time and was thus one of the only Russian billionaires who was relatively unaffected by the crisis. In his early 40s, he could have easily retired and focused on his hobbies (he is said to work out twice a day, and he loves kickboxing and heli-skiing).

Instead, Prokhorov decided to go into politics. As the case of Mikhail Khodorkovsky shows, this step is not without dangers for Russian oligarchs. When Khodorkovsky, then the richest man in Russia, began funding the opposition and publicly criticizing Putin on government corruption in 2003, he was arrested and has been in prison ever since.

Prokhorov was more careful. In the spring of 2011, he became the head of the pro-business party Pravoe Delo (“Right Cause”). According to Alexei Kudrin, the former finance minister under Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, this happened with the Kremlin’s explicit consent. The goal was to reposition the party under Prokhorov so that it would secure the Kremlin the votes of the business community and parts of the urban elite.

Prokhorov invested $100 million of his own money in the party. However, after only four months, an intraparty coup removed him. Although the reasons for this coup remain unclear, Hans-Henning Schröder, a political scientist at the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik in Berlin, and numerous other analysts believe it was the Kremlin that toppled Prokhorov because he became too unpredictable and independent.Prokhorov’s personal and political background makes his rationale as a candidate for the presidency all the more puzzling. Some, like Russian political scientist Stanislav Belkovsky of the National Strategy Institute, believe that the Kremlin orchestrated Prokhorov’s candidacy. Belkovsky called it “the Kremlin’s answer to Bolotnaya Square,” referring to the large protests in Moscow. There are certainly indicators for this thesis: Vladislav Surkov, Kremlin mastermind and “father” of the political philosophy of Sovereign Democracy, stated in an interview Dec. 6 that Russia needed a new liberal party that could give a political home to “annoyed” city residents. Furthermore, Putin could be interested in an opposition candidate to lend the presidential elections, which he is sure to win, more legitimacy.

Prokhorov has always denied any explicit agreements between himself and the Kremlin. He has, however, stated that criticism of Putin would be no more than 10 percent of his program. Putin said that Prokhorov was a worthy competitor with many ideas that were right for the country. Prokhorov has even acknowledged that the Kremlin wanted to use his candidacy to bolster the legitimacy of the elections: “They want to play with democracy so that people have ‘some kind of a choice.’ The authorities want to use us for their own understandable goals, but we will use them.”

All that this set of facts proves, however, is that the Kremlin does not consider Prokhorov’s candidacy an immediate threat — especially because of the unpopularity of oligarchs in Russia. The pollsters agree: In all recent surveys, Prokhorov’s potential is estimated at 5 to 10 percent of the electorate.

On the other hand, “Prokhorov is a glamorous oligarch and he’s got plenty of money to spend on promoting himself,” said Sergei Markov, a professor of political science at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations. Running for president without a powerful party in the background takes some resources indeed. Prokhorov needs to collect 2 million signatures before Jan. 18 in order to submit his candidacy. The theory that Prokhorov’s campaign is motivated mainly by his idiosyncratic personality is also corroborated by the fact that it appears rather improvised. An anonymous member of the billionaire’s campaign staff told The New Times that Prokhorov’s decision had been “spontaneous,” and that there had been “no preparations.”

One thing that is clear at this point is that the Kremlin could use its “administrative resources” to stop Prokhorov’s candidacy if this was politically desired. The Central Election Commission did ban the candidacy of Eduard Limonov, the head of the controversial National Bolsheviks. So far, nothing indicates that Prokhorov will be banned. He is not expected to demand any radical reforms, he does not have an interest in changing the distribution of wealth in the country, and he has so far not attacked the government very harshly. Of the demands he put forward, the release of Khodorkovsky and the reduction of the presidential term by one year have been the most radical.

To what extent Prokhorov manages to attract the support of the Russian opposition that is not represented in the Duma remains to be seen. Navalny said that he might run for president himself, and liberal opposition leader Boris Nemtsov considers Prokhorov to be in cahoots with Putin. The candidate himself has been very careful not to get too involved with the non-systemic opposition. Prokhorov participated in the large rally Dec. 24 in Moscow, but he did not address the crowd.

One effect Prokhorov’s candidacy has had, however, is to enliven Russia’s political landscape. There are now seven candidates who will compete with Putin, all of whom are expected to get between 5 and 10 percent of the vote. Mikhail Vinogradov, head of the St. Petersburg Policy Foundation, thus considers it possible that the current prime minister will not receive the absolute majority of votes in the first round of elections. Having to go into a second round would be a humiliation for the most powerful man in Russia, who is struggling with waning popularity. It could foreshadow a time when Putin is not the default winner of Russian presidential elections.

Ivo Mijnssen is a Russia scholar who specializes in youth movements in contemporary Russia, Soviet patriotism and the memory of World War II. In the spring, his book on the youth movement Nashi will be published by the ibidem-Verlag in Germany.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.