The New Permanent Campaign

In 1976, a young political consultant named Patrick Caddell sent a memo to Jimmy Carter telling the president-elect to wage "a continuing political campaign" that fuses public policy and political goals. This doctrine became known as the permanent campaign, and it is now changing from a White House tactic into a national grass-roots organizing strategy.In 1976, a young political consultant named Patrick Caddell sent a memo to Jimmy Carter telling the president-elect to wage “a continuing political campaign” that fuses public policy and political goals. This doctrine became known as the permanent campaign, and it is now changing from a White House tactic into a national grass-roots organizing strategy.

Today’s permanent campaign aims to ensure that the recent surge in Democratic voter turnout becomes the foundation of a lasting political infrastructure for progressives, rather than a momentary boomlet of presidential election euphoria. That means “creating mechanisms for people to remain engaged in politics between elections,” as Thomas Bates says.

He co-founded Democrats Work, a nonprofit group whose mission was on display when 12 volunteers of varying ages gathered last week to prepare dinner for residents at a Denver homeless shelter. The participants were not just giving back to their city — they were becoming Democratic Party activists.

“Lots of folks want to do community service but are not political,” says Erin Egan, who runs the 500-member Colorado branch of Democrats Work. “But when they volunteer with us, they see the Democratic Party’s values and often become committed political volunteers.”

For many activists already involved in Democratic politics, the permanent campaign is an extension of their enthusiasm for Howard Dean’s reformist presidential candidacy in 2004. But the emergence of another organization named Blue Tiger Democrats shows that the new efforts actually hearken back to Tammany Hall.

That 19th century New York political machine may be known for corruption, but it drew its true strength from being a service organization.

Tammany Hall built Democratic loyalty by running everything from soup kitchens to job banks. Blue Tiger, which takes its name from Tammany’s feline symbol, supports the same kind of “civic engagement,” as founder Bill Samuels calls it. And unlike Democrats Work, which is an outside group, Blue Tiger emulates Tammany Hall by working directly inside the Democratic Party.

“People only see the Democratic Party at election time, and that has to change,” says Mark Brewer, the Michigan Democratic chairman who, along with New York party officials, is employing Blue Tiger’s methods. In the forgotten corners of both states, Blue Tiger sponsors food drives, roadside cleanups and computer training seminars — all under the banner of the Democratic Party.

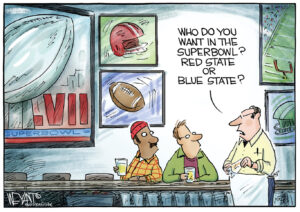

Democrats Work and Blue Tiger Democrats are merely two examples of Democrats’ renewed focus on turnout and base participation — a more logical priority than the party’s old “swing” strategies that concentrate exclusively on winning independents. After all, Republican strongholds like Colorado, Nevada and Ohio contain overwhelmingly Democratic population centers. A sustained turnout boost in those cities could easily tip statewide results — and thus, alter the national political map.

But changing red states to blue states is only one objective of the permanent campaign. Deepening the hue of existing blues is another.

Just weeks ago, progressive activist Donna Edwards crushed Maryland Rep. Al Wynn in a Democratic primary. She attacked the more conservative incumbent for supporting lobbyist-written legislation that helps banks gouge consumers. Edwards won her underdog race thanks, in part, to two other wings of the permanent campaign: Liberal blogs helped her raise money, and groups like the Service Employees International Union aided her get-out-the-vote operations.

The support, along with the presidential primary hype, doubled the district’s turnout over the last election. Edwards, who lost the contest two years before, won the same race by a wide margin and is now the presumptive general-election winner. In other words, the rise in Democratic turnout helped the more progressive candidate win. Such a dynamic could be replicated in other down-ballot races if the permanent campaign succeeds in raising voter turnout for good. And over time, that would move the Democratic Party in a more populist direction.

“We had a message saying we have to divorce ourselves from corporate special interests,” Edwards says. “And [Democratic leaders] are going to have to get comfortable with that message.”

When Caddell originally wrote to Carter, Democrats needed a permanent campaign to combat an ascendant Republican Party and a conservative movement learning to exploit the country’s economic concerns. Now, with America in a similarly anxious mood, today’s permanent campaign could bring about a Democratic era and a powerful progressive movement. Throughout history, those two factors have been the key prerequisites for positive change.

David Sirota is a best-selling author whose newest book, “The Uprising,” will be released in June. He is a fellow at the Campaign for America’s Future and a board member of the Progressive States Network — both nonpartisan organizations. His blog is at www.credoaction.com/sirota.

© 2008 Creators Syndicate Inc.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.