The NBA Presents an Instant Rivalry for the Age of Hyper-Engagement

In the past, sports rivalries -- notably in baseball -- evolved and played out over decades. The rise of the NBA shows how much things have changed. Stephen Curry, left, of the Golden State Warriors knocks the ball loose from the Cleveland Cavaliers' LeBron James in the first half of an NBA game on Jan. 18 in Cleveland. (Tony Dejak / AP)

Stephen Curry, left, of the Golden State Warriors knocks the ball loose from the Cleveland Cavaliers' LeBron James in the first half of an NBA game on Jan. 18 in Cleveland. (Tony Dejak / AP)

Rivalries are to sports what a triple shot of espresso is to breakfast: You can have a nourishing meal without it, but it’s not the same.

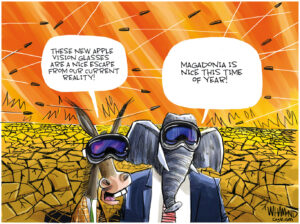

Unlike politics in which rivalries spring up overnight — such as Donald Trump versus Jeb Bush, Rand Paul, Chris Christie et al. — those in sports are traditionally organic, developing over years as opposed to being something capable of being manufactured at league offices’ convenience.

Authentic rivalries like Lakers versus Celtics and Yankees versus Red Sox call on something deeper than fandom, like regional pride and cultural self-image, selling them.

Attempts to hype lesser matchups in the absence of memorable play are DOA.

If baseball officials greeted the Royals-Mets World Series as a classic matchup of East Coast megamarket and heartland village, it turned out to be a humdrum event, even with the wrong New York team.

The Mets are the players that few outside Gotham give any thought to, as opposed to the Yankees, whom the rest of America has loved to hate since the 1950s when there was a Broadway play about that national animus (titled, of course, “Damn Yankees”).

With the Royals dispatching the Mets in five games, the series drew an 8.7 TV rating, the fourth in a row under 10.0.

Of course, baseball is handy for looking at traditional patterns — which is the sport’s problem with its storied past, recalled by its aging audience as it struggles to attract young viewers, or even get them to play the game (cue the MLB’s RBI program, or Reviving Baseball in the Inner Cities).

These days young viewers flock to the NBA, once the runt of U.S. leagues, dismissed by old-line columnists who largely worked their way up off the baseball beat as a “YMCA league.”

Now a league that’s 74.4 percent African-American, according to Richard Lapchick’s Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, is second only to the NFL, as measured by annual network dollars.

The NFL, which took over Sunday from organized religion, as the Albert Brooks character notes in the movie “Concussion,” harvests $9 billion annually in network rights fees.

The NBA will go to $2.7 billion next season, from its current $930 million. Baseball gets $1.55 billion from its deals, which went into effect in 2014.

The NBA’s value lies in its appeal to the youth demographic, since its marquee telecasts are only slightly higher-rated, with the last five Finals averaging a 9.5 to the last five World Series’ 8.7.

In 2013 Paulsen of Sports Media Watch noted that no game of the World Series between the Red Sox and Cardinals — two of the most storied franchises — got more than 25 percent of its audience from the 2-34 age group.

The 2013 NBA Finals between Miami and San Antonio went seven games, each of which got at least 37 percent of its audience from the 2-34s.

This makes the NBA handy for looking at modern hyper-penetration, because young fans follow on myriad platforms — notably mobile phones, the be-all and end-all of modern commerce, as well as social networks.

It’s like the Apple ad that says, “The only thing that has changed is everything.”

Rivalries that took decades to develop before the Internet age, when fans waited until 11:30 p.m. to get scores from the sports segment of the local TV news show, now take months.

Under the old rules, last spring’s Golden State-Cleveland matchup would have been little noted nor long remembered.

The Warriors had only recently risen from their niche as have-nots, making their first Finals appearance in 40 years.

The Cavaliers had LeBron James, a ratings magnet to be sure but less of a villain after going home to Cleveland, which he had betrayed to (all together now) take his talent to South Beach.

The series was relatively one-sided, although it lasted six games — a feat for the Cavaliers, who dragged it out with Kevin Love missing it all and Kyrie Irving going out in Game 1.

It nevertheless drew a boffo 10.3 rating, the highest Finals since Michael Jordan’s heyday in Chicago in the 1990s, the NBA’s zenith.

The NBA built its Christmas package around the Warriors and Cavs, suddenly partners in a marquee matchup as if they were from Los Angeles and Boston instead of Oakland and Cleveland, and got its third-highest TV rating for a regular season game since 1999.

The Warriors, widely dismissed as defending champions — Clipper Coach Doc Rivers, speaking for the rest of the league, noted how “lucky” they were to miss his team, not to mention the Spurs — showed everyone with their NBA record 24-0 start.

If nothing of consequence in the NBA is won in December (or, indeed, before June), the Warriors are so big, Jay Crawford apologized for talking about them so much on “SportsCenter,” noting ESPN is aware there are other NBA storylines.

The Warriors’ Steph Curry, who plays wonder tyke to Bron’s bionic man, now outsells James’ jersey and everyone else’s.

With the NBA’s following in China, an outgrowth of Yao Ming’s time, the San Francisco Chronicle wasn’t exaggerating by much when it noted in a headline, “Warriors’ popularity sweeping nation, world.”

The new-age NBA is confident enough to air ads with Steph Curry, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul and Joakim Noah advocating gun control during its Christmas games. Even with an audience that skews Democratic, it’s unprecedented daring for a U.S. sports league.

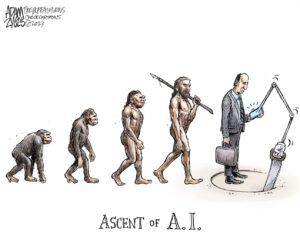

Not that hyper-penetration is merely a sports phenomenon. In anything the media touch, things that were small are now big. Things that were big now blot out the sun.

In the hyperventilating coverage of the runup to the 2016 presidential primaries, social media are as much a part of the environment as Politico, Daily Kos and RedState. Pew Research Center found 52% of people on Twitter and 47% of those on Facebook use the platforms as sources for news.

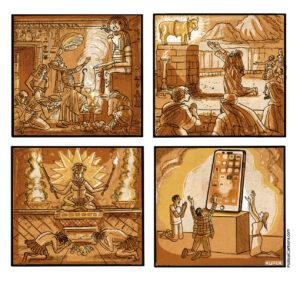

The result is a preoccupation with the immediate and the loss of the bigger picture, ignoring the lessons of history.

The New York Times’ Paul Krugman marvels at GOP candidates who continue to advance failed policies, such as putting boots on the ground in the Middle East, as if they haven’t resulted in national debacles so recently. Whatever else is involved, modern media make it seem as if everyone starts fresh every day.

Whether it’s wiser or dumber, it’s a hyper-world. As Sgt. Phil Esterhaus in “Hill Street Blues” used to tell his people, “Hey, let’s be careful out there.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.