The Limited Reach of the Supreme Court’s Gay Marriage Rulings

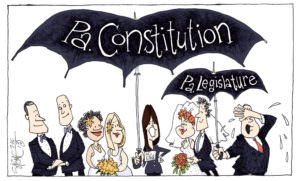

How proponents of marriage equality and progressives generally proceed from this point depends on understanding exactly what Wednesday’s decisions on DOMA and Proposition 8 said and didn’t say. To do that, we must look beyond the headlines. Given the narrow reach of the court’s rulings in the DOMA and Proposition 8 cases, here are three takeaways for marriage equality proponents.

From Greenwich Village in New York to West Hollywood and the Castro District in California, the LGBT community is celebrating, and for good reason. In two landmark rulings handed down Wednesday, the Supreme Court overturned a key section of the Defense of Marriage Act in the case of United States v. Windsor and paved the way for same-sex marriages to resume in California in Hollingsworth v. Perry.

But as the parades, rallies and public displays of pure giddiness wind down, let’s hope that a more sobering realization sets in that despite Wednesday’s triumphs, the court’s decisions fall far short of establishing marriage equality as a federal constitutional right. The decisions may have advanced the ball significantly in that direction, but they were, in fact, narrow and bitterly divided 5-4 rulings issued by a deeply conservative tribunal that erect stiff barriers to further progress, both for the cause of marriage equality and the broader goals of social justice extending beyond the issue.

How proponents of marriage equality and progressives generally proceed from this point depends on understanding exactly what Wednesday’s decisions said and didn’t say. To do that, we must look beyond the headlines.

Of the two rulings, Windsor has the wider nationwide application. Authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy and joined by the court’s four liberals, the majority opinion held that Section 3 of DOMA, which defines marriage for purposes of more than a thousand federal laws and benefit programs as the union of one man and one woman, violated the basic principles of due process and equal protection of the U.S. Constitution’s Fifth Amendment. In heartfelt prose that spoke of the sanctity and dignity of same-sex unions, Kennedy reasoned that the section’s only purpose was to impose a “separate status and so a stigma” upon same-sex couples, and that such purpose was unconstitutional.

Threaded within Kennedy’s heartfelt prose, however, was a narrative of states-rights and old-fashioned federalism, whereby he and the majority recognized that with few constitutional exceptions (pertaining, for example, to now-defunct state laws prohibiting interracial unions), the definition of marriage is by historical tradition and the weight of constitutional law left to the states. The majority opinion did not alter that tradition with regard to gay marriage. To the contrary, the opinion ends with the stark admonition that “its holding [is] confined to those lawful marriages” in states that have opted to recognize same-sex unions.

In those fortunate jurisdictions, currently comprising 13 states and the District of Columbia, LGBT couples may now enjoy the same federal benefits for Social Security, medical coverage, income tax filing and other programs as heterosexual married partners. For the rest of the country, a regime of separate and unequal will still persist, legally untouched by the Windsor ruling.

The decision also left unresolved the thorny issue of what will happen to a same-sex couple’s federal benefits when they relocate from a state where same-sex marriage is legal to one where it’s not recognized. Rather than answering this question once and for all, the Windsor majority invites a new and costly round of needless litigation, the outcome of which is uncertain.

The majority opinion in the Hollingsworth case fell even wider of the mark of establishing a nationwide right for gay couples to wed. The opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts — and joined by liberal Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer and the increasingly unhinged Antonin Scalia, who had railed against the dangers of homosexual sodomy in his Windsor dissent — dismissed on highly technical federal “standing” grounds the appeal that had been brought by the proponents of California’s Proposition 8, the ballot initiative that voters passed in the 2008 election outlawing gay marriage. Justices Kennedy and Sonia Sotomayor dissented, along with Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, preferring a decision on the merits of the measure’s constitutionality.

The dismissal, while not unexpected, represented a lost opportunity to establish marriage equality as a fundamental right for all. As I wrote in a Truthdig column posted after oral arguments were heard in the case in March, a dismissal would have the effect of reinstating the ruling handed down in 2010 by former U.S. District Judge Vaughn Walker, who invalidated Proposition 8 on equal protection grounds as lacking any rational legal basis. That has now happened.

Although the net result of the dismissal will be the resumption of same-sex marriages in California — possibly within the next 30 days — the Hollingsworth opinion, like the Windsor ruling, will have no legal force and effect in other states. Indeed, Roberts was clear in stating that the court majority did not question California’s sovereign right to maintain an initiative process, or by extension the right of other states to maintain their own processes. But for the courage of Walker, whose own sexual orientation was outrageously raised as an issue during the course of the litigation, California would be faced with a continuing ban on gay marriage that the Supreme Court likely would have left intact.

Given the narrow reach of the court’s rulings in Windsor and Hollingsworth, here are three takeaways for marriage equality proponents:

1. Even the most conservative court operates in a political context and can be moved in a liberal direction by broad and irreversible shifts in public attitudes and values. Ten years ago, even the limited victories of Windsor and Hollingsworth would have been unthinkable.

2. Despite Windsor and Hollingsworth, the Roberts court remains the most conservative Supreme Court since the early 1930s, consistently ruling on behalf of business interests and often at the expense of long-established civil liberties under the guise of an alarming states-rights canon. In fact, just the day before the Windsor and Hollingsworth opinions were announced, the court followed that canon and ripped the heart out of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in its Shelby County v. Holder decision.

3. Above all: The most effective way to achieve full marriage equality is to join that fight with broader struggles for social justice. It’s a cliché, I know, but it bears invocation: United we stand, divided we fall.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.