The Importance of Being Exceptional

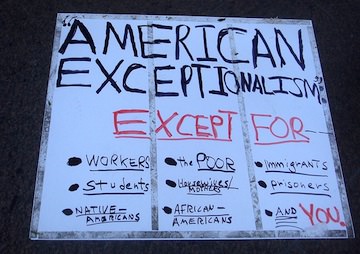

Why is it immoral for a person to treat himself as an exception? The reason is plain: because morality, by definition, means a standard of right and wrong that applies to all persons without exception. Yet to answer so briefly may be to oversimplify. Photo by Jagz Mario (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Photo by Jagz Mario (CC BY-SA 2.0)

By David Bromwich, TomDispatchThis piece first appeared at TomDispatch. Read Tom Engelhardt’s introduction here.

The origins of the phrase “American exceptionalism” are not especially obscure. The French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville, observing this country in the 1830s, said that Americans seemed exceptional in valuing practical attainments almost to the exclusion of the arts and sciences. The Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, on hearing a report by the American Communist Party that workers in the United States in 1929 were not ready for revolution, denounced “the heresy of American exceptionalism.” In 1996, the political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset took those hints from Tocqueville and Stalin and added some of his own to produce his book American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword. The virtues of American society, for Lipset — our individualism, hostility to state action, and propensity for ad hoc problem-solving — themselves stood in the way of a lasting and prudent consensus in the conduct of American politics.

In recent years, the phrase “American exceptionalism,” at once resonant and ambiguous, has stolen into popular usage in electoral politics, in the mainstream media, and in academic writing with a profligacy that is hard to account for. It sometimes seems that exceptionalism for Americans means everything from generosity to selfishness, localism to imperialism, indifference to “the opinions of mankind” to a readiness to incorporate the folkways of every culture. When President Obama told West Point graduates last May that “I believe in American exceptionalism with every fiber of my being,” the context made it clear that he meant the United States was the greatest country in the world: our stature was demonstrated by our possession of “the finest fighting force that the world has ever known,” uniquely tasked with defending liberty and peace globally; and yet we could not allow ourselves to “flout international norms” or be a law unto ourselves. The contradictory nature of these statements would have satisfied even Tocqueville’s taste for paradox.

On the whole, is American exceptionalism a force for good? The question shouldn’t be hard to answer. To make an exception of yourself is as immoral a proceeding for a nation as it is for an individual. When we say of a person (usually someone who has gone off the rails), “He thinks the rules don’t apply to him,” we mean that he is a danger to others and perhaps to himself. People who act on such a belief don’t as a rule examine themselves deeply or write a history of the self to justify their understanding that they are unique. Very little effort is involved in their willfulness. Such exceptionalism, indeed, comes from an excess of will unaccompanied by awareness of the necessity for self-restraint.

Such people are monsters. Many land in asylums, more in prisons. But the category also encompasses a large number of high-functioning autistics: governors, generals, corporate heads, owners of professional sports teams. When you think about it, some of these people do write histories of themselves and in that pursuit, a few of them have kept up the vitality of an ancient genre: criminal autobiography.

All nations, by contrast, write their own histories as a matter of course. They preserve and exhibit a record of their doings; normally, of justified conduct, actions worthy of celebration. “Exceptional” nations, therefore, are compelled to engage in some fancy bookkeeping which exceptional individuals can avoid — at least until they are put on trial or subjected to interrogation under oath. The exceptional nation will claim that it is not responsible for its exceptional character. Its nature was given by God, or History, or Destiny.

An external and semi-miraculous instrumentality is invoked to explain the prodigy whose essence defies mere scientific understanding. To support the belief in the nation’s exceptional character, synonyms and variants of the word “providence” often get slotted in. That word gained its utility at the end of the seventeenth century — the start of the epoch of nations formed in Europe by a supposed covenant or compact. Providence splits the difference between the accidents of fortune and purposeful design; it says that God is on your side without having the bad manners to pronounce His name.

Why is it immoral for a person to treat himself as an exception? The reason is plain: because morality, by definition, means a standard of right and wrong that applies to all persons without exception. Yet to answer so briefly may be to oversimplify. For at least three separate meanings are in play when it comes to exceptionalism, with a different apology backing each. The glamour that surrounds the idea owes something to confusion among these possible senses.

First, a nation is thought to be exceptional by its very nature. It is so consistently worthy that a unique goodness shines through all its works. Who would hesitate to admire the acts of such a country? What foreigner would not wish to belong to it? Once we are held captive by this picture, “my country right or wrong” becomes a proper sentiment and not a wild effusion of prejudice, because we cannot conceive of the nation being wrong.

A second meaning of exceptional may seem more open to rational scrutiny. Here, the nation is supposed to be admirable by reason of history and circumstance. It has demonstrated its exceptional quality by adherence to ideals which are peculiar to its original character and honorable as part of a greater human inheritance. Not “my country right or wrong” but “my country, good and getting better” seems to be the standard here. The promise of what the country could turn out to be supports this faith. Its moral and political virtue is perceived as a historical deposit with a rich residue in the present.

A third version of exceptionalism derives from our usual affectionate feelings about living in a community on the scale of a neighborhood or township, an ethnic group or religious sect. Communitarian nationalism takes the innocent-seeming step of generalizing that sentiment to the nation at large. My country is exceptional to me (according to this view) just because it is mine. Its familiar habits and customs have shaped the way I think and feel; nor do I have the slightest wish to extricate myself from its demands. The nation, then, is like a gigantic family, and we owe it what we owe to the members of our family: “unconditional love.” This sounds like the common sense of ordinary feelings. How can our nation help being exceptional to us?

Teacher of the World

Athens was just such an exceptional nation, or city-state, as Pericles described it in his celebrated oration for the first fallen soldiers in the Peloponnesian War. He meant his description of Athens to carry both normative force and hortatory urgency. It is, he says, the greatest of Greek cities, and this quality is shown by its works, shining deeds, the structure of its government, and the character of its citizens, who are themselves creations of the city. At the same time, Pericles was saying to the widows and children of the war dead: Resemble them! Seek to deserve the name of Athenian as they have deserved it!

The oration, recounted by Thucydides in the History of the Peloponnesian War, begins by praising the ancestors of Athenian democracy who by their exertions have made the city exceptional. “They dwelt in the country without break in the succession from generation to generation, and handed it down free to the present time by their valor.” Yet we who are alive today, Pericles says, have added to that inheritance; and he goes on to praise the constitution of the city, which “does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves.”

The foreshadowing here of American exceptionalism is uncanny and the anticipation of our own predicament continues as the speech proceeds. “In our enterprises we present the singular spectacle of daring and deliberation, each carried to its highest point, and both united in the same persons… As a city we are the school of Hellas” — by which Pericles means that no representative citizen or soldier of another city could possibly be as resourceful as an Athenian. This city, alone among all the others, is greater than her reputation.

We Athenians, he adds, choose to risk our lives by perpetually carrying a difficult burden, rather than submitting to the will of another state. Our readiness to die for the city is the proof of our greatness. Turning to the surviving families of the dead, he admonishes and exalts them: “You must yourselves realize the power of Athens,” he tells the widows and children, “and feed your eyes upon her from day to day, till love of her fills your hearts; and then when all her greatness shall break upon you, you must reflect that it was by courage, sense of duty, and a keen feeling of honor in action that men were enabled to win all this.” So stirring are their deeds that the memory of their greatness is written in the hearts of men in faraway lands: “For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb.”

Athenian exceptionalism at its height, as the words of Pericles indicate, took deeds of war as proof of the worthiness of all that the city achieved apart from war. In this way, Athens was placed beyond comparison: nobody who knew it and knew other cities could fail to recognize its exceptional nature. This was not only a judgment inferred from evidence but an overwhelming sensation that carried conviction with it. The greatness of the city ought to be experienced, Pericles imagines, as a vision that “shall break upon you.”

Guilty Past, Innocent Future

To come closer to twenty-first-century America, consider how, in the Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln gave an exceptional turn to an ambiguous past. Unlike Pericles, he was speaking in the midst of a civil war, not a war between rival states, and this partly explains the note of self-doubt that we may detect in Lincoln when we compare the two speeches. At Gettysburg, Lincoln said that a pledge by the country as a whole had been embodied in a single document, the Declaration of Independence. He took the Declaration as his touchstone, rather than the Constitution, for a reason he spoke of elsewhere: the latter document had been freighted with compromise. The Declaration of Independence uniquely laid down principles that might over time allow the idealism of the founders to be realized.

Athens, for Pericles, was what Athens always had been. The Union, for Lincoln, was what it had yet to become. He associated the greatness of past intentions — “We hold these truths to be self-evident” — with the resolve he hoped his listeners would carry out in the present moment: “It is [not for the noble dead but] rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”

This allegorical language needs translation. In the future, Lincoln is saying, there will be a popular government and a political society based on the principle of free labor. Before that can happen, however, slavery must be brought to an end by carrying the country’s resolution into practice. So Lincoln asks his listeners to love their country for what it may become, not what it is. Their self-sacrifice on behalf of a possible future will serve as proof of national greatness. He does not hide the stain of slavery that marred the Constitution; the imperfection of the founders is confessed between the lines. But the logic of the speech implies, by a trick of grammar and perspective, that the Union was always pointed in the direction of the Civil War that would make it free.

Notice that Pericles’s argument for the exceptional city has here been reversed. The future is not guaranteed by the greatness of the past; rather, the tarnished virtue of the past will be scoured clean by the purity of the future. Exceptional in its reliance on slavery, the state established by the first American Revolution is thus to be redeemed by the second. Through the sacrifice of nameless thousands, the nation will defeat slavery and justify its fame as the truly exceptional country its founders wished it to be.

Most Americans are moved (without quite knowing why) by the opening words of the Gettysburg Address: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers…” Four score and seven is a biblical marker of the life of one person, and the words ask us to wonder whether our nation, a radical experiment based on a radical “proposition,” can last longer than a single life-span. The effect is provocative. Yet the backbone of Lincoln’s argument would have stood out more clearly if the speech had instead begun: “Two years from now, perhaps three, our country will see a great transformation.” The truth is that the year of the birth of the nation had no logical relationship to the year of the “new birth of freedom.” An exceptional character, however, whether in history or story, demands an exceptional plot; so the speech commences with deliberately archaic language to ask its implicit question: Can we Americans survive today and become the school of modern democracy, much as Athens was the school of Hellas?

Teacher of the World

Athens was just such an exceptional nation, or city-state, as Pericles described it in his celebrated oration for the first fallen soldiers in the Peloponnesian War. He meant his description of Athens to carry both normative force and hortatory urgency. It is, he says, the greatest of Greek cities, and this quality is shown by its works, shining deeds, the structure of its government, and the character of its citizens, who are themselves creations of the city. At the same time, Pericles was saying to the widows and children of the war dead: Resemble them! Seek to deserve the name of Athenian as they have deserved it!

The oration, recounted by Thucydides in the History of the Peloponnesian War, begins by praising the ancestors of Athenian democracy who by their exertions have made the city exceptional. “They dwelt in the country without break in the succession from generation to generation, and handed it down free to the present time by their valor.” Yet we who are alive today, Pericles says, have added to that inheritance; and he goes on to praise the constitution of the city, which “does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves.”

The foreshadowing here of American exceptionalism is uncanny and the anticipation of our own predicament continues as the speech proceeds. “In our enterprises we present the singular spectacle of daring and deliberation, each carried to its highest point, and both united in the same persons… As a city we are the school of Hellas” — by which Pericles means that no representative citizen or soldier of another city could possibly be as resourceful as an Athenian. This city, alone among all the others, is greater than her reputation.

We Athenians, he adds, choose to risk our lives by perpetually carrying a difficult burden, rather than submitting to the will of another state. Our readiness to die for the city is the proof of our greatness. Turning to the surviving families of the dead, he admonishes and exalts them: “You must yourselves realize the power of Athens,” he tells the widows and children, “and feed your eyes upon her from day to day, till love of her fills your hearts; and then when all her greatness shall break upon you, you must reflect that it was by courage, sense of duty, and a keen feeling of honor in action that men were enabled to win all this.” So stirring are their deeds that the memory of their greatness is written in the hearts of men in faraway lands: “For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb.”

Athenian exceptionalism at its height, as the words of Pericles indicate, took deeds of war as proof of the worthiness of all that the city achieved apart from war. In this way, Athens was placed beyond comparison: nobody who knew it and knew other cities could fail to recognize its exceptional nature. This was not only a judgment inferred from evidence but an overwhelming sensation that carried conviction with it. The greatness of the city ought to be experienced, Pericles imagines, as a vision that “shall break upon you.”

Guilty Past, Innocent Future

To come closer to twenty-first-century America, consider how, in the Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln gave an exceptional turn to an ambiguous past. Unlike Pericles, he was speaking in the midst of a civil war, not a war between rival states, and this partly explains the note of self-doubt that we may detect in Lincoln when we compare the two speeches. At Gettysburg, Lincoln said that a pledge by the country as a whole had been embodied in a single document, the Declaration of Independence. He took the Declaration as his touchstone, rather than the Constitution, for a reason he spoke of elsewhere: the latter document had been freighted with compromise. The Declaration of Independence uniquely laid down principles that might over time allow the idealism of the founders to be realized.

Athens, for Pericles, was what Athens always had been. The Union, for Lincoln, was what it had yet to become. He associated the greatness of past intentions — “We hold these truths to be self-evident” — with the resolve he hoped his listeners would carry out in the present moment: “It is [not for the noble dead but] rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”

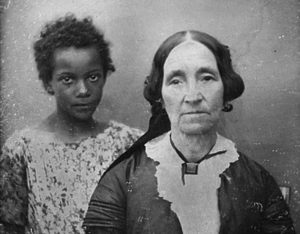

This allegorical language needs translation. In the future, Lincoln is saying, there will be a popular government and a political society based on the principle of free labor. Before that can happen, however, slavery must be brought to an end by carrying the country’s resolution into practice. So Lincoln asks his listeners to love their country for what it may become, not what it is. Their self-sacrifice on behalf of a possible future will serve as proof of national greatness. He does not hide the stain of slavery that marred the Constitution; the imperfection of the founders is confessed between the lines. But the logic of the speech implies, by a trick of grammar and perspective, that the Union was always pointed in the direction of the Civil War that would make it free.

Notice that Pericles’s argument for the exceptional city has here been reversed. The future is not guaranteed by the greatness of the past; rather, the tarnished virtue of the past will be scoured clean by the purity of the future. Exceptional in its reliance on slavery, the state established by the first American Revolution is thus to be redeemed by the second. Through the sacrifice of nameless thousands, the nation will defeat slavery and justify its fame as the truly exceptional country its founders wished it to be.

Most Americans are moved (without quite knowing why) by the opening words of the Gettysburg Address: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers…” Four score and seven is a biblical marker of the life of one person, and the words ask us to wonder whether our nation, a radical experiment based on a radical “proposition,” can last longer than a single life-span. The effect is provocative. Yet the backbone of Lincoln’s argument would have stood out more clearly if the speech had instead begun: “Two years from now, perhaps three, our country will see a great transformation.” The truth is that the year of the birth of the nation had no logical relationship to the year of the “new birth of freedom.” An exceptional character, however, whether in history or story, demands an exceptional plot; so the speech commences with deliberately archaic language to ask its implicit question: Can we Americans survive today and become the school of modern democracy, much as Athens was the school of Hellas?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.