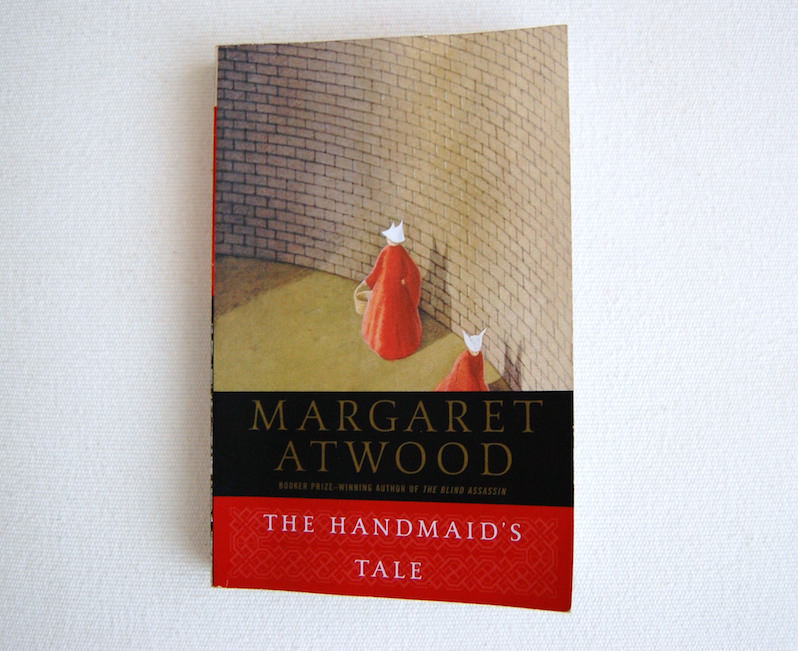

The Handmaid’s Tale

Margaret Atwood's classic dystopian novel is a recipe book for how to create a hellish society. It's also a recipe book for how to resist. Flickr / CC 2.0

Flickr / CC 2.0

|

To see long excerpts from “The Handmaid’s Tale” at Google Books, click here. |

“The Handmaid’s Tale” A book by Margaret Atwood

If there is an urtext of modern feminism, especially for those of us who prefer it in the form of juicy dystopian novels instead of lofty essays, then Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” is probably the closest thing we’ve got. It’s one of those books that people believe can tell a lot about another person based on what that other person thought of it.

Is your new boyfriend woke enough? Has he read “The Handmaid’s Tale”?

Is your new book club smart enough? How do they discuss “The Handmaid’s Tale”?

The Handmaid’s Tale

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

The Handmaid’s Tale

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Has your relationship with your repressed Protestant mother festered for so long that you have never considered her as a complex woman with a rich inner life and her own unrealized desires and fears? Pour her a merlot and give her “The Handmaid’s Tale.” That ought to get you somewhere, even if it’s somewhere you later wish you hadn’t gone.

It means something to people — deeply, politically and almost spiritually. The new Hulu adaptation (starring Elisabeth Moss and Alexis Bledel) is a lot of things, but mostly it’s validation for those fans among us who don’t do cosplay as a rule, but who understand exactly the symbolism and the power of red capes and white bonnets.

READ: “‘The Handmaid’s Tale’: A Harrowing Warning From a Fictional Future to a Tense Present“

Like a lot of good speculative fiction, describing the plot ends up short-selling the story, but for those who haven’t read it we’ll try: In a near-future universe of rising sterility and falling birthrates, the United States has been taken over by a right-wing theocracy. To rebuild the population, the new government has reintroduced the biblical practice of forced surrogacy (Remember Rachel and Leah and their fertile handmaids in Genesis?).

Rich women get to be wives to “Commanders.” Other women, if they can still bear children like the book’s heroine, Offred, are made into handmaids. Sent to training centers to learn obedience. Made to wear red. Not allowed to control finances or read. All told in spare, ironic prose with not an extra ounce of flesh on it.

The book was published in 1985 to near-glowing acclaim, winning the Arthur C. Clarke prize, nominated for a Booker Prize and a Nebula Award. One exception was the review written by Mary McCarthy, herself a famous novelist, who criticized “Handmaid’s Tale” for simultaneously being too unbelievable and not creative enough. “Nothing like the linguistic tour de force, ‘A Clockwork Orange,'” she sneered in The New York Times.

Which — thank God, because some of us can’t stand that book. And which, moreover, elaborately misses the point. “The Handmaid’s Tale” didn’t need linguistic cartwheels to transport its readers to an unfathomable new world. “Handmaid’s” world was meant to be fathomable — same technology, same cities, same fretting over women’s bodies — and its horrors were not all that new.

Over the years, it’s been assigned in college literature classes, yanked out of school libraries, celebrated and denigrated and feared and loved. Legions of women first found it on their mothers’ bookshelves, or on the bookshelves of cool aunts or babysitting clients, an introduction to the messiness of womanhood.

It’s been banned. Of course it’s been banned, appearing on the American Library Association’s list of the top 100 banned books of the decade, for both the 1990s and 2000s. People said it was anti-Christian (it’s not, just anti-crazy fundamentalist) — or had too much disturbing sex. Astute readers might point out that anyone who singled out the sex as the disturbing element wasn’t paying enough attention. The true terror of the book isn’t the acts people commit, but the mindset — the brainwashed masses lulled into accepting the unthinkable as the ordinary — that allows people to commit them.

And what does Margaret Atwood, the creator of this world, think of all of this?

We met with her, recently, sitting on straight-backed chairs in the sort of generically opulent hotel suite that could have been one of the Commanders’ parlors, but which today had been repurposed as an interview room. Next door, cast and crew of the series are in their own interview rooms; outside, a long line of journalists — all female, all appearing to be in their 30s — await their own time slots to ask Atwood the same questions she has patiently answered over and over in the course of three decades.

“Could it happen? How close are we?” says Atwood, 77, sharing what those questions typically are. “Especially, ‘How close are we?’ Especially that. When the book first came out in England, people said, ‘Jolly good yarn,’ because they’d already had their religious civil war. The Canadians, who are quite diverse, might not be able to gain the critical mass required to attain a monolithic theocracy. But Americans, it was either, ‘It can’t happen here, don’t be silly,’ or ‘How close are we?'”

She doesn’t know the answer. She doesn’t know how close we are, as a society, or if we’re close at all. She doesn’t know what happens to Offred at the end of the novel. She doesn’t even know Offred’s real name. Over decades, readers decided it was “June” based on contextual clues — June is the only character name, introduced in a roll call, who is not otherwise accounted for — but it was never Atwood’s original intent.

“I created a vacuum and it was filled,” she says. “Not in an inappropriate way, but it wasn’t my idea.”

She wrote the book on a typewriter in 1984, and it happened in fits and starts because she just kept worrying it was too weird to present to an editor. Then she showed a draft to a trusted friend and said, “I think I’m going to get a lot of hate mail,” and the friend said, “I think you’re going to be rich,” and both of them were right. And decades passed, and the book kept growing.

“Some books escape from the book itself, and this is one of them,” she says. “It’s been a film. It’s been an opera — a really good opera. It’s been a ballet. It’s being a graphic novel right now. It turns up as memes in elections. It’s about to be a television series. It’s recently been proposed to me that it should be a video game. Although I cannot begin to imagine what that would be like.”

She wafts a hand. “It’s out of the box. I feel as though it’s no longer something I have control over. Not that you ever have control over the book.”

Our time is up. We were given only 20 minutes! We wanted to know so much more! But she has other people to see. That night we will go see Atwood sit on a panel presented by the Smithsonian Associates, in which all of the questions we thought to ask are asked yet again, by all of the devoted fans.

There was an essay a few years back by feminist comedian Lindy West about the television show “Law & Order: SVU,” and why so many women are compelled to watch a show in which week after week, bad things happen to women. “Watching SVU is like pressing a bruise,” West wrote — a way to exorcise one’s deepest fears in the safe confines of television.

One wonders if “The Handmaid’s Tale” presses that same bruise. Because the book is essentially a page-turning tour through every conceivable female nightmare. Loss of independence. Subjugation at the hands of men. Rape. Violence. Losing a child, or being thought of as less-than for being childless. All of it state-sanctioned.

This is what lead actress Elisabeth Moss remembers about her first reading of the book, back when she was a teenager. We talk about it with her, when we are shuffled over to her hotel suite. After her first reading, she didn’t hang on to the plot specifics, she says, so much as she was affected by the sense that she could be going about her business in a modern, everyday society, and then the next day be stripped of her rights and place in the world.

“And,” she says, “nobody would come to help you.” She thought about that for years. She thought about whether she was worthy to play a character that had impacted her so intensely.

It’s inevitable that classic works are repurposed and reinterpreted in current contexts. A few weeks ago, a group of women walked purposefully into the Texas state legislature building wearing red capes and bonnets — handmade handmaids — protesting what they saw as the restriction of women’s reproductive rights. Around the same time, some right-wing viewers who saw the show’s trailer online criticized it in the comments as “anti-Trump propaganda.” This led another commenter to respond, “If you see ‘The Handmaid’s Tale,’ written over 30 years ago, as a subtweet at your political movement, what does that say about your movement?”

Go ahead and read it as social commentary — Atwood doesn’t mind if you do. She knows “The Handmaid’s Tale” belongs to the world now. Or go ahead and read it just as a thought experiment, divorced from current events, for what it would look like to have a world upended and for how to maintain sanity when that happens.

But just as it is a recipe book for how to create a hellhole, it’s also a recipe book for how to resist one — whether that resistance happens by flouting the rules, or by learning how to work them for one’s own benefit, or whether the resistance happens only in the quietude of one’s mind. Free thoughts, in an un-free space.

It’s a really good book.

©2017, The Washington Post

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.