The Ghost of Giuliani’s Political Past

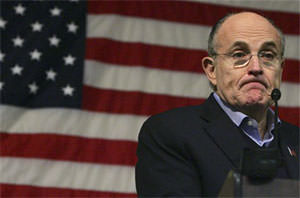

Rudy Giuliani is often presented as a political moderate whose thriving presidential campaign need only negotiate the hurdle of a conservative primary, but his pre-9/11 record as New York's mayor -- particularly his policies toward working-class and minority residents -- should greatly alarm progressives.

According to the latest Quinnipiac poll, if the 2008 election were held today Rudy Giuliani would be our next president. Given his stature as a media celebrity, the numbers are not surprising. A fixture on the cable talk shows, Giuliani in fact announced his candidacy on Larry King.

In New York City, the former mayor is regularly and shamelessly promoted by Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post, which recently featured Giuliani kissing his former mistress and now wife, Judi Nathan, on its cover.

Based on the poll numbers and flattering media coverage, you might think there indeed is some kind of national love affair going on between Giuliani and the American people. But rest assured that there is one place where the former mayor is truly despised: the streets of working-class New York.

The school where I teach, Metropolitan College of New York, is a commuter school made up of the city’s working-class students, the vast majority of whom are blacks and Latinos from the outer boroughs. Recently, I showed my classes the 2006 documentary “Giuliani Time,” which is now available on DVD.

Before starting the film, I received a flurry of hostile reactions — e.g., “Is this going to make me sicker than I already feel?” and “This is going to make me angry!” When the documentary ended, not one of my 35 students had a kind word for Giuliani. In fact, the most frequent question asked was a fearful one: “Do you really think he could win?”

Why is there such contempt for the man who never tires of reminding audiences of how he “saved” the city after 9/11? As “Giuliani Time” makes abundantly clear, it’s because in the eight years he reigned as New York City mayor leading up to 9/11, Giuliani ruled as a petty tyrant. And the most frequent target of his animosities was the city’s black population.

After defeating the city’s only black mayor, David Dinkins, in 1993, Giuliani made it crystal clear that he was not interested in a dialogue about race relations. During his first month in office, Giuliani ended the city’s affirmative action program established under Dinkins. For most of the next eight years, he conspicuously refused to meet with any of the city’s black political leadership.

In the documentary, Giuliani’s one high-ranking black political appointee during his two terms, schools Chancellor Rudy Crew, voices his displeasure with his former boss. Crew recalls his surprise when Giuliani announced that he would pursue a school vouchers program, a policy that promised to further deprive the city’s many poor students of color of educational resources. It was during the Amadou Diallo controversy, Crew says, when he realized that there “is something very deeply pathological” about Giuliani’s views of race.

During his two terms, Giuliani’s two biggest policy initiatives — reducing welfare rolls and fighting crime — also antagonized the city’s low-income populations of color. His much-touted Workfare initiative amounted to an increase in the numbers of the city’s working poor, undercutting better-paying city jobs in the process. And as Village Voice reporter and Giuliani foe Wayne Barrett says in the film, “No one knows what happened to the 600,000 people” who disappeared from the welfare rolls during the Giuliani years.

In terms of crime, Giuliani’s overzealous “quality-of-life” policing effectively amounted to a full-fledged crackdown on young men of color, as documented by the NYPD’s record number of wrongful “stop-and-frisk” encounters. Prior to his post-9/11 “heroics,” Giuliani was best known for having “cleaned up New York.” But as Columbia University’s Jeffrey Fagan and others make clear in “Giuliani Time,” crime dropped even more dramatically in other major cities during the 1990s — and many of those cities did not employ the racially biased quality-of-life approach of Giuliani’s NYPD.

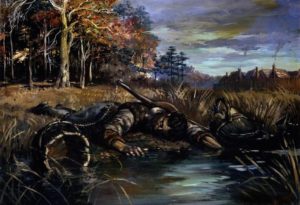

In 1999, after four undercover white police officers shot Diallo, an unarmed African immigrant, 41 times, Giuliani described the thousands of pro-Diallo protesters as “silly” and the “worst in society.” A few months later when Patrick Dorismond, an unarmed black man, was killed by an undercover officer, Giuliani said that the victim was “no choirboy” and ordered his juvenile arrest record to be unsealed. Dorismond, in fact, had been a choirboy.

By Sept. 10, 2001, Giuliani had pissed off wide swaths of New York City’s population, including free speech advocates, artists and middle-class liberals of all kinds. If we judge him based on his actions during his two terms in office, rather than by the two weeks after 9/11, the thought of Rudolph Giuliani becoming president should alarm most progressives. And for people of color in New York City and elsewhere, the prospect is terrifying.

Theodore Hamm is the founding editor of The Brooklyn Rail and an associate professor of urban studies at Metropolitan College of New York.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.