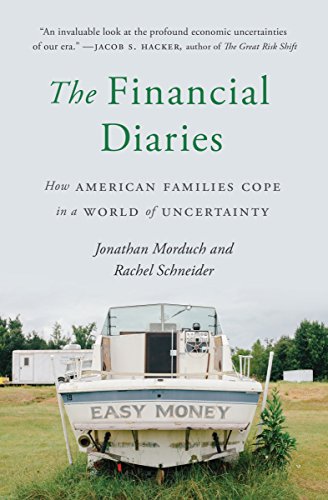

The Financial Diaries

A new book explores the lives of families dealing with financial uncertainty and volatility. Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press

“The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty”A book by Jonathan Morduch and Rachel Schneider To see long excerpts from “The Financial Diaries” at Google Books, click here.

Buying in bulk. Skipping a utility bill. Waiting for a tax refund. Borrowing cash from mom. If you’ve done one or more of these, you’re not the first to get creative with managing your money, or more specifically, the lack thereof. And if you think more and more people are having to find ways to deal with financial instability, you’re right. There’s more of us that live with uncertainty than ever before and even those who are not poor all the time sometimes experience months of living below the poverty line.

Our newly elected president has promised to create 25 million new American jobs in the next decade. Just for the record, that would be more jobs created than under any other president in history. Go bigly (or big league) or go home.

But until those 25 million jobs materialize, what are anxious Americans supposed to do? In their book “The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty,” Jonathan Morduch and Rachel Schneider explore this new world of volatility and reveal the different strategies families have developed to deal with the financial uncertainty that pervades their daily lives. The superrich may be getting even wealthier, and the destitute may be getting even poorer, but “the instability of families’ incomes has risen faster than the inequality of families’ income,” Morduch and Schneider write.

Collecting a financial diary is as laborious as it sounds. Rather than simply note a family’s annual income and spending, Morduch and Schneider created a detailed, comprehensive, day-to-day survey to record how money moves in and out of a household. They believe cash flow to be a crucial piece of the puzzle lacking in many economic studies. The breadth and the scope of the diaries required a level of participation from families that was akin to allowing a documentary film crew into one’s home. Researchers sat down and worked to earn the trust of families whose financial disclosures could often be embarrassing and difficult to reveal. Indeed, more than half of the families selected would drop out at some point. Yet by the end of the yearlong study, some families wished the researchers could stick around longer — the study had helped them focus their attention on their spending habits. By the time their year with the 235 remaining families was over, the researchers had collected a staggering amount of detailed data, “just under 300,000 cash flows over the course of 2012 and 2013, including everything from buying a pack of gum at the local convenience store to making a down payment on a newly purchased car.” Though names and certain details about the families have been altered for anonymity, the stories of the families provide the backbone of “The Financial Diaries,” and humanize what may otherwise be an increasingly depressing series of graphs and charts.

The story of Sarah and Sam Johnson typify the plight of many of the families in “The Financial Diaries.” They live in a three-story house in a relatively safe suburb of Cincinnati, with two kids in high school from previous marriages and their preschooler, Amy. Neither graduated college; they both work. But while “their jobs were steady, their expenses were unpredictable and volatile.” In the year of “The Financial Diaries,” “Their cars broke down on at least three occasions. [When] their two older children graduated high school … they threw a graduation party, then learned [their daughter] Ann had decided to marry her sweetheart — the following week.” And when it rains, it pours, sometimes literally: A couple of months later, a water pipe sprung a leak in their home, which cost them $1,400 to repair. To add insult to injury, “The water damage aggravated Amy’s asthma, which required a trip to the doctor and the pharmacy … [and] the leak caused a substantial bump in their water bill.”

So was it just this series of unfortunate events that led Sarah and Sam to skip utility bills and max out credit cards? And despite bad luck, isn’t it their fault for not saving up for unexpected expenses? Morduch and Schneider argue that despite being frugal spenders and even smart savers, people like Sam and Sarah will always be swimming upstream. The problem is that the social contract that used to help families like the Johnsons no longer exists, thanks to what the authors call The Great Job Shift.

The Great Job Shift can be thought of as the shift of risk and cost from large institutions like governments and corporations to families and individuals, who have a profoundly weaker ability to absorb those risks. Starting in the ’70s, finding a job “that pays a predictable and living wage has become increasingly difficult to find.” Technology is an obvious contributor to the shift; many manufacturing jobs gave way to automation and jobs disappeared. Technology is also responsible for software that can “estimate precisely how many workers [a company] will need, down to the day and time. This can lead to dramatic swings in the number of hours that employees work, depending on the season, month, week and even the day.” The result: workers with wildly unsteady hours, sometimes with fluctuations that “average almost 50 percent. … Schedules were not just volatile but unpredictable, even a week in advance.”

Technology isn’t all to blame. When it comes to higher education, funding for public universities dwindled as state governments shifted a greater amount of the cost to families: “According to the College Board, college costs are rising four times faster than income and two and half times faster than federal Pell grants.” Less access to education means less access to decent wages.

But companies are the biggest contributors to The Great Job Shift, as “employers that had once provided their workers with pensions and comprehensive health insurance and folded the costs of risk management into their business plans had begun to shift more of those costs onto workers.” Sarah and Sam both had health insurance through their jobs, but Sam’s was a low-premium, high-deductible plan and when he needed care, the costs rose. For their family, health care was debilitating:

In the previous five years, medical bills had piled up: $2,800 for surgery for Sam; $1,000 for MRIs for Sarah; $700 for an emergency room visit for [their son] Mathew; and the largest bill, $3,800, for a company that offers a credit card for health expenses.

Add to that the stagnation of wages, and families nowadays are “hit with a double whammy: they have to shoulder the extra costs and are then less prepared for other challenges.” The Great Job Shift has ushered in a time of great volatility and given rise to a class of new citizens whose name belongs in a post-apocalyptic novel: the precariat (a combination of precarious and proletariat), those suffering from precarity. Precarity, of course, describes the condition of living a precarious existence.

The precariats in “The Financial Diaries” do all they can to smooth out what is otherwise a roller-coaster financial life, marked by spikes and dips in income and spending. Becky became a couponer and stockpiled “toothpaste, shampoo, body wash and razors. … She also had a buffer of canned goods in the pantry and frozen food in the freezer.” Robert takes full advantage of anything he can get for free: “Most things I do, I do for free. I can get free movie tickets online, so I don’t have to pay for the movies.” He also pays only $100 a month to stay on his mother’s couch. Sandra withdrew money from an IRA, rather than go down the difficult road of credit card debt she had suffered through before, sacrificing long-term savings for immediate needs. Taisha was “forced to use her rent money toward the utilities.” Mateo and his wife participate in tandas or “Roscas (rotating savings and credit associations),” informal but binding sharing and saving agreements within a community.

Some smoothing methods create more problems. Janice, a card dealer at a casino, resorted to payday loans during a particularly bad offseason. Now, she puts her savings in a bank 35 miles away, without an ATM. Out of sight, out of mind.

But despite their best efforts, it becomes painfully clear that for the families in the “Diaries,” “insufficiency of resources is accompanied by instability. … Insolvency is accompanied by illiquidity.” This is the double-whammy of The Great Job Shift. Morduch and Schneider expose what ails families today, and their diagnosis is equally grim:

In today’s America, families bear a larger share of economic risk than ever before. Employers have pushed the costs of business ups and downs onto their workers, banks and other financial institutions have left families unprotected, and the government safety net has failed to meet the challenges of people experiencing ups and downs.

Morduch and Schneider mention a few potential cures throughout their discussion, like apps that automate saving, and other possible solutions, from better jobs to better financial tools, but their intent with “The Financial Diaries” is not simply to provide a backdrop for the important discussion of public policy. To them, the backdrop is the story. In “The Financial Diaries,” they seek to pull away from the big numbers and focus on the people behind those annual reports and government spreadsheets, bringing much-needed perspective and nuance into the economic discussion. For me, “The Financial Diaries” was a reality check: I’m fortunate, and in the more literal sense of the word than I often choose to acknowledge.

Many American families must choose between saving and surviving. “The Financial Diaries” makes it agonizingly clear just how difficult it is for many of our fellow Americans. And yet, despite the difficulties and seemingly endless setbacks, the “Diaries” families continue to find ways to support their families, to give their kids a Christmas, to help other family members in need. They rarely sought to be wealthy, only to struggle a little bit less, to breathe a little easier, to maybe start to save. But as a nation, this is not enough. We should not be satisfied that families simply cope. More must be done to allow hardworking families to achieve the financial security we all deserve.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.