The Fat Line Between Free Speech and Defamation

When criticized, many followers of one faith or another mistakenly perceive a personal attack, and tend to elevate the sacredness of their own individual beliefs at the expense of universal free expression, thus sullying the discourse before it can even begin.

This article was originally featured on The Huffington Post.

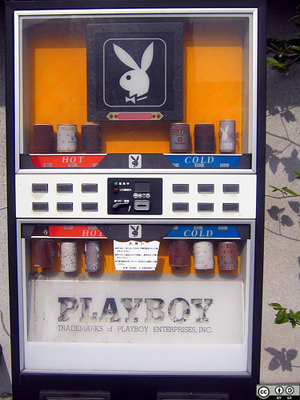

For many religious believers around the world, the credulity with which they defend their faith is oftentimes only matched by the incredulity with which they receive ridicule. The latest example is the response to a campaign by the Atheist Agenda on the campus of the University of Texas in San Antonio called “Smut for Smut,” wherein anyone who wishes may exchange a religious text for print pornography, such as Playboy or Penthouse. [Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article misidentified the campus involved. As a reader pointed out, it is the University of Texas in San Antonio, not in Austin.]

Atheist Agenda’s most obvious goal is to make a scene through a bold and inflammatory — but legally accorded — display of its right to free speech. The message is that modern forms of pornography are equally as perverse, depraved and misogynist as portions of traditional, mainstream religious texts. (Judges 19: 25 – 28 comes to mind.)

The immediate religious counter-response in Texas and around the nation — though self-indicting — is that AA is unfairly cherry-picking from religious texts. According to the school paper, The Paisano, throngs of religious — mostly Christian — believers showed up to form a counter-protest, shrilly condemning the perceived insult to their holy book, and playing right into AA’s hands. Also, interestingly, a faction of professed “agnostics” arrived to stand as a voice of reason separately between the two groups, both of whom they consider equally guilty of intolerance.

The Smut for Smut campaign tactic resembles that used recently by others of a similar ilk, whereby the goal is to make light of what seems so obviously ridiculous to the average nonbeliever. Good examples are Bill Maher’s 2008 film, “Religulous,” and Ariane Sherine’s bus advertising campaign in the United Kingdom, about a year ago, where the message, “There’s probably no God. So stop worrying and enjoy your life,” was plastered across the side of a number of London city metros.

The reaction from religious groups to Maher and Sherine — as on the Texas campus this week — was predictable. Many felt offended, violated — and, notably, discriminated against — that others would make jest of that which they hold so sacred. Meanwhile, the atheists were presumably only more amused by the widespread sprint to indignation. For the taunting atheists, this is good, clean fun. But for some of the faithful, such messages are perceived as an almost existential attack — one where defense mechanisms kick in.

In the mild version of such altercations, we get what happened in Austin this week. Some of the protesters maintained full respect for AA’s right to speak its piece. One student reportedly carried a sign that read, “Jesus loves the Atheist Agenda.” Others were less lenient, and deemed Smut for Smut “inappropriate” and “offensive,” with one reportedly ripping down a Smut for Smut campaign banner. Another student, Adam Zepada from nearby Saint Mary’s University, told The Paisano, “I wanted to call up some homeboys and be like ‘hey dawg, I wanna go up there and take care of it real quick.’ But, because I’m saved and I gave my life to Christ in 2007, I don’t live like that anymore.”

Fair enough, Zepada has chosen restraint in his actions; but his kneejerk instinct to “take care of it real quick” resonates eerily with other recent events. Just ask Kurt Westergaard, the Danish cartoonist who has remained more or less in hiding since his inflammatory depiction of Muhammad in 2005. [Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article erroneously referred to Westergaard as being Dutch.] Or British columnist Johann Hari, who provoked riots and death threats a year ago when he called out the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights for prioritizing Islam’s delicate immunity from criticism above free expression.

In the U.S., though the reaction is usually less violent (but not always), its nature is still the same. A good example is the off-with-his-head cries sportswriters hear anytime they criticize Tim Tebow for participating in Evangelical Christian message campaigns.

The outspoken Zepada from the anti-Smut for Smut protest, incidentally, almost sets a good example for strict religious belief. But his reaction still reveals the inherent defensiveness that comes with being an unquestioning believer — a defensiveness that, for some, can hew towards obstinacy and militancy. When criticized, many followers of one faith or another mistakenly perceive a personal attack, and tend to elevate the sacredness of their own individual beliefs at the expense of universal free expression, thus sullying the discourse before it can even begin.

Though the boilerplate issue here is the dispute between religious defamation and freedom of expression, the core operative element is a profound but generally unaddressed double standard between some form of religious faith and none at all. If you are a Christian, Jesus was God’s one and only son; if you are a Muslim, Jesus was just the second-to-last prophet before Muhammad. But if you are a professed atheist who criticizes either of these opinion-based notions, then you can be accused of just being judgmental and offensive, even though taking a position on this is no different to the nonbeliever than taking a position on gun control laws or cap-and-trade.

As long as the fundamental divide between adherents to the numerous world faiths and those who adhere to none remains irreconcilable, the area where we all can — and must — converge is on how we go about actually having the conversation. Violence or terror, most obviously, are unacceptable. But the milder form so often practiced by believers — a puerile refusal to allow one’s ideas to be criticized at all — can be just as prohibitive to the conversation. Atheist Agenda’s jab was at a few ancient texts, not at any person. If ideas and sources are not open for criticism, then nothing is.

Some nonbelievers, surely, can go too far when ridiculing religion, and there is plenty of room to censure them in this regard. But they do it because they rightfully can. When the religious response moves from condemning a rhetorical tactic to condemning the very act of criticism — as if the notion of faith falls under some arbitrary plafond of immunity — fair discourse is effectively blocked. This subtle but monumental distinction has remained far more pronounced elsewhere around the world, especially in predominantly Islamic states, but whiffs of it can always be sensed here as well when groups like the Atheist Agenda stir the pot.

In a free society, shrill reactions to religious criticism will invite only more of the same. Religious believers should develop a sense of humor with which to respond to secular ridicule. Up till this point, many are still just asking for it.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.