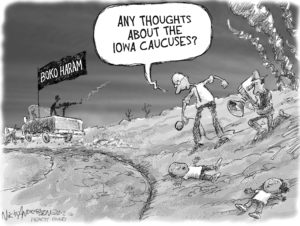

‘The Failed State Chick’ on Boko Haram

"The abduction of the girls is, of course, an extremely grave crime," journalist Corinne Dufka says. "But to focus exclusively on the girls lacks an appreciation of the wide and systematic crimes committed by Boko Haram in recent years, and also by the Nigerian army since the state of emergency was declared almost a year ago.""To focus exclusively on the girls lacks an appreciation of the wide and systematic crimes committed" in recent years, journalist Corinne Dufka says.

The New York Times carried a poignant blog post last week about Camille Lepage, a 26-year-old photojournalist killed earlier this month in the Central African Republic. The chief Africa photographer for The Associated Press, Jerome Delay, paid Lepage the ultimate insider’s compliment, calling her “this very discreet yet inquisitive and incredible journalist” in the tradition of Corinne Dufka.

Dufka is the most famous journalist you never heard of. She denies that women do journalism differently, but her persona suggests otherwise. Dufka is a quiet iconoclast who belies the tradition of the pompous foreign correspondent who boasts about the bullets he’s dodged and the dictators he’s known, a club that until recently has been mostly, but not exclusively, male.

Dufka, for example, would never mention her 2003 MacArthur “Genius” Grant, although she’s competitive enough to be annoyed that she missed out on a Pulitzer because her photographs were deemed too negative.

Nearly 20 years ago, Dufka left journalism to join Human Rights Watch, becoming its senior researcher in West Africa. Last week, she found herself in the midst of a breaking news story again, as an international furor arose over the kidnapping of nearly 300 girls by the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram. After the story went viral — complete with a frowning Michelle Obama holding up a sign with the hashtag #bringbackourgirls — a counter-furor arose. Jumoke Balogun, an American born in Nigeria and a correspondent for The Guardian, charged that the campaign would provide a pretext for further U.S. military involvement in Africa.

Instead of going all Kony2012 on Michelle Obama, I called Dufka. She began her career as a social worker in El Salvador, worked as a photojournalist in Bosnia, and joined the Reuters bureau in Nairobi, Kenya, in the early 1990s. For the next decade, the “dirty wars” in West Africa were her beat. After joining Human Rights Watch, she took a year’s leave of absence to work for the Special Court for Sierra Leone investigating war crimes and human rights abuses.

Susan Zakin: Let’s start with the girls kidnapped by Boko Haram in Nigeria. What is the press getting wrong?

Corinne Dufka: They’re not getting anything wrong, it’s just an incomplete picture. The abduction of the girls is, of course, an extremely grave crime. But to focus exclusively on the girls lacks an appreciation of the wide and systematic crimes committed by Boko Haram in recent years, and also by the Nigerian army since the state of emergency was declared almost a year ago. There have been scores of attacks on towns and villages, and well over 1,000 people killed, hacked to death, dragged out of their cars and murdered. Scores of boys and young men have been killed in school attacks.

SZ: Have schools been a particular target?

CD: The name “Boko Haram” means Western education is sin. They have opposed Western education from the very beginning, and schools are among their main targets. They’ve attacked and burned schools of all different levels, from primary and secondary schools to technical and academic colleges. As recently as March, 43 students were hacked to death in a government college. The abduction of the girls is just one of many attacks against educational institutions.

SZ: What has the government of Nigeria done to stop them?

CD: In response to death threats by Boko Haram, the Nigerian army has set up widespread and arbitrary detention, in horrible conditions that have led to the deaths of many men without court proceedings to determine their guilt or innocence. There could be a campaign “Bring Back our Boys” led by the mothers of boys and men who are arbitrarily detained. Many have died. We met with numbers of these women. It was heartbreaking. Both sides have committed violations. It’s important to keep that in mind.

SZ: Is there something unique about Boko Haram?

CD: Boko Haram seems to be a disturbing fusion between the Sierra Leone rebel movement in the 1990s and al-Qaida. The tactics used in Sierra Leone were designed to terrify. The RUF — the Revolutionary United Front — compensated for their low numbers by terrifying the population and swelling their ranks as people joined them out of fear. Boko Haram is also using sheer terror to intimidate and ultimately control the population. They profess to be grounded in Islam but an Islam that, as many scholars have pointed out, is against the principles of Islam.

SZ: You’ve worked in a number of countries known as failed states. What have you learned about the causes of state failure?

CD: Rapid population growth is one factor. Some West African countries have the highest population growth in the world. No country can keep up with that. Climate change, desertification, economic factors and, lastly, endemic corruption. But Nigeria is not a failed state. It has very strong institutions, a strong central government, a strong media, a strong electoral process. The problem with Nigeria is not that it’s a failed state but a deeply corrupt state. Boko Haram started out years ago preaching against corruption. Followers gravitated toward a group that seems to offer them more than the state does.

SZ: Boko Haram has been expanding its violent activities for several years. We weren’t paying much attention to Nigeria before the girls were kidnapped, were we?

CD: Not enough. We shouldn’t only zoom in on places where the conflict is already surfacing. The fact that Mali, which essentially collapsed two years ago, was considered a success story by the West is an indictment of development policy. It’s a culture of low expectations. As long as there are elections that are not characterized by extreme violence, as long as there is not overt armed conflict, then a country stays out of the problem category.SZ: What are the signs we should be looking for?

CD: The growth of fundamentalist religion happens for a reason. In Africa, it’s rooted in the failure of ethnic and tribal structures, as well as the government, to address the basic needs of the population: health, education, clean water. I would include the opportunity to flourish as necessary for a healthy society. Into that vacuum creeps what I call the meddlers. In past decades the meddlers were rebel groups like the ones we saw in Sierra Leone and Liberia. They were supported by Moammar Gadhafi, Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso and others who benefited from resource exploitation by the meddlers. The modern day meddlers are drug traffickers from South America, who are using West Africa as a route to sell their wares in Europe, as well as religious fundamentalists.

SZ: Critics are charging that #bringbackourgirls is an excuse to expand the U.S. military presence in Nigeria, one of the world’s largest oil producers.

CD: Business interests are already involved. I think the U.S. is more concerned about the security implications.

SZ: Speaking of security, how closely allied to al-Qaida is Boko Haram?

CD: The extent to which they are allied with al-Qaida isn’t really clear. That’s a work in progress; it’s gone back and forth.

SZ: Boko Haram has been fairly tough to characterize until now, partly because it’s been too dangerous for journalists to travel to the north. In general, covering wars is more dangerous now. Is that why we’re becoming fascinated by the people who do this work?

CD: It’s a manifestation of the cult of personality that infects our society. But it’s true that the conflicts are getting more dangerous.

SZ: Is there a personality type for people attracted to the work?

CD: They’re all fucked up [laughs]. No, not really.

SZ: Samantha Power called herself “the genocide chick,” which helped make her a star. Aren’t you the original genocide chick?

CD: Wouldn’t Martha Gellhorn be the original genocide chick?

SZ: So you’re the failed state chick.

CD: I’m the failed state chick.

SZ: It’s a great sound bite, the chick thing, but what’s the reality? When French photographer Camille Lepage died [this month] in the Central African Republic, The New York Times compared her photographs to yours because of their emotional impact. We need to be careful about attributing differences to gender, but is there something different about the way women cover war?

CD: It was very sad. But in terms of differences, I don’t think so. I really don’t. I’ve never bought into that. Women do not have a monopoly on paying attention to emotional issues.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.