The Egg and I

Not only does the story testify to the power of humor to sustain a real-life parable celebrating the ingenuity of a man hoping to escape the mundane, but it is also proof that the scenic, circuitous route through life may be preferable to the more direct.When I was in the eighth grade, I was arrested for throwing eggs at a pedophile’s house.

As a teenager, world-renowned Oscar Wilde/Cindy Brady genius hybrid Truman Capote worked as a copy boy in the art department at The New Yorker. This was in the early 1940s, and one of his responsibilities, in addition to sorting cartoons for Saul Steinberg and William Steig and George Price, was to deliver the famously ill-tempered and blind humorist James Thurber to his mistress’ apartment at the end of the day. Capote would wait in the living room while the couple engaged in the sort of rowdy lovemaking that he later described as the sound of hogs being butchered. He would then dress Thurber and return the satiated lecher home, oftentimes fall-down drunk, to his wife, who would undress him for bed. The helplessness of his ward made Capote feel servile and invisible, like a nanny hired to mollycoddle a spoiled rotten baby with the same exact daily routine, Monday through Friday, that began with a few drinkie-poos, followed by a walkie-poo, then an obstreperous ejaculation into a homely secretary, then a changing, then another walkie-poo and then beddy-bye.

Finally bored beyond tolerance by the scut work, Capote decided, while dressing Thurber one afternoon, to put the old man’s socks on inside out. Predictably, Thurber’s wife, who had dressed her husband in the morning, demanded an explanation as to why it had appeared he needed to remove his socks during the day, to which the celebrated wit is rumored to have quipped, “That fucking little queer.” (Pause to allow Eustace Tilley the Walter Mitty-esque daydream of believing that he is not really just Alfred E. Neuman in silk pantaloons and a $300 hat.) Needless to say, as a result of the inverted socks, Capote was immediately relieved of his professional obligation to Thurber’s vas deferens and, 70 years later, the artfulness of his extrication can still be enjoyed as thoroughly as if it were an exquisitely rendered poem designed expertly for repeated recitation.

Specifically, not only does the story testify to the power of humor to sustain a real-life parable celebrating the ingenuity of a man hoping to escape the mundane, but it is also proof that the scenic, circuitous route through life may be preferable to the more direct. Had Capote merely decided to end his association with Thurber by complaining privately to Harold Ross, the magazine’s editor at the time, or by quitting, not only would the delectability of the original story have been lost forever, but so too would the example that the human experience could, at times, be lived with grace and artistry.

When I was in the eighth grade, I was arrested for throwing eggs at a pedophile’s house. Let’s say that her name was Deloris Keating, not true, and that I was NOT chew-my-own-foot-off jealous that my 14-year-old friend, Richie, was the one having sex with her and not me, also not true, though both details are necessary for the streamlining of the narrative. She was old, real old, maybe 31, and freshly divorced with three young children. Richie was her baby sitter, and every Tuesday and Thursday night he would use a hair pick to inflate his North Jersey wopfro into a Don Henley, comb the porn star prototype mustache resting on his upper lip with a dry toothbrush, slap on enough Brut Cologne to bruise the air and walk to her house around the corner like he was Youngblood Priest in “Super Fly.” He would then watch television and drink chocolate milk with Deloris’ kids, feed them macaroni and cheese on plastic Hanna-Barbera plates, get them into their pajamas and tuck them into their beds. Then, sometime around 11 o’clock, his employer would come home and take off her pants, open her blouse, turn on a porno film and rub up against her hire, stinking of Long Island Iced Teas and cigarette smoke. Minus the diseased and psychotic manipulation of a minor, plus the inexplicable preference for Betamax over VHS, it was a real Romeo and Juliet romance. That is, until Richie thought that it would be a laugh-riot to take the 17-inch zucchini she had in her bedside table, bake it at 350 degrees for an hour and return it back to its drawer as soft as a gargantuan green alien stool sample.

“What do you mean, what did she say?!” he barked back at me with watery eyes, momentarily forgetting that anybody with whom an adolescent boy is having sex is not so much a sex partner as an interloper encroaching on the magnificent love affair he is already having with his own genitalia. “She was pissed off — said that I was too fucking immature for her! Can you believe that shit?” he said, trying to keep the contents of his “Spider-Man” Trapper Keeper from spilling out all over the bus stop.

Five days later, on the night before Halloween, he and I, along with my big brother, Jeff, a guy named Philhower and a guy named Danny, crept out of the woods on the other side of the street in front of Deloris’ house, the pockets of our jackets and hooded sweatshirts loaded with eggs, our claustrophobic blood pounding in our ears, our nervous systems overrun with something like electric spiders. I don’t remember much following the order to FIRE! except that the one and only egg I threw missed its target completely and sailed over the roof. Then I remember, almost immediately, somebody yelling RUN! amid the mayhem of yolks exploding against shingles and shutters, at which point we ran, not for the woods, but as a sloppy disparate mob set zigzagging down the street like morons trying to outrun eyesight.

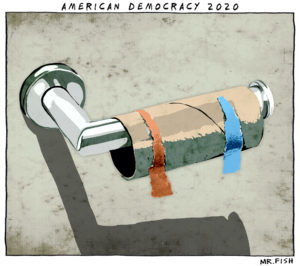

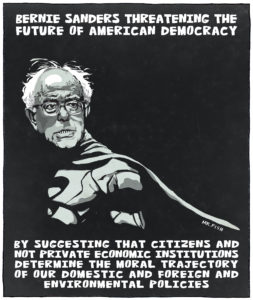

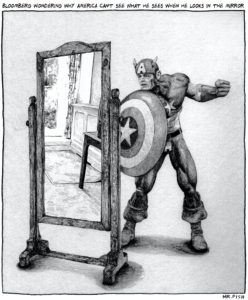

The thing about art, and I include folklore to be part of that discipline, is that it will always deepen the historical record that defines our moral and immoral certitude by insisting that the human heart, with all its contradictions and inarticulate universality, be present at the existential committee convened for the comprehension of life itself. Straight journalism, for example, or the rote memorization of theocratic balderdash or the cataloging of scientific data are certainly insufficient compilers of all that comprises the complicated identity of the whole species. Consider how unremarkable and ineffectual the 1950s and ’60s would’ve been had the only commentary available to us been that of Walter Cronkite, Bishop Sheen and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Or try processing the great Dante-esque calamity that was the Second World War without such books as “The Naked and the Dead,” “Catch-22” and “Slaughterhouse-Five.” Additionally, no one would even know that there was ever a labor movement in this country that was vibrant and effective in teaching people how to organize and to gain both civil and workers rights had there never been Woody Guthrie, John Steinbeck or Thomas Hart Benton.

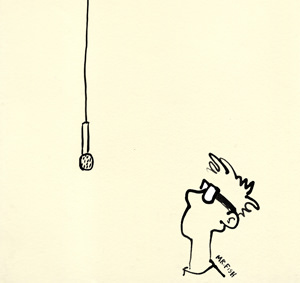

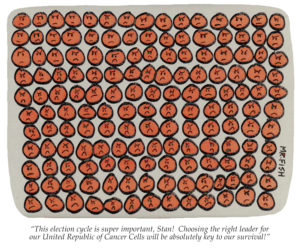

“I worry because I don’t see any significant artwork being produced nowadays to help deepen our understanding of recent historical events beyond whatever sound bites we’re given by the 24-hour news cycle,” I said, standing behind a commie-red podium in front of a crowd at Revolution Books in lower Manhattan after a presentation of my cartoons. This was on the night before the night before the NYPD was covertly scheduled to dismantle the Occupy Wall Street encampment at Zuccotti Park and to wage the only sort of war that the U.S. power structure seems willing to fight anymore, both domestically and internationally. That is the sort launched against the defenseless and, preferably, the sleeping, the heroism of the cops and soldiers involved typically being determined by how squarely they’re able to shoot their target in the back.

“There’s no poetry in the retelling or re-examination of what we’ve been through over the last decade because there is no artistry in the way the memory has been rendered,” I said, locking eyes with a kid in the front row who had just gotten into town from Duluth to join the fledgling OWS resistance movement as a photographer. “What source material will our children have access to when it comes to making sense of 9/11, for example? Who are they going to quote, the great Wolf Blitzer? ‘In My Time’ by Dick Cheney? It’s fucking ridiculous and we’re running out of time! Nothing will be remembered if we don’t feel like retelling the story!”

“Are you going to let him burn alone or are you going to stand up like men?” asked Officer Von Schmidt, gesturing toward a rather sullen-looking Richie while strutting back and forth in front of us in his jackboots and breeches, the brim of his policeman’s cap hiding his eyes. We had been picked up by a pair of squad cars just a few blocks away from Deloris’ house and returned, with egg on our shoes, to her front yard for positive identification. Nobody said a word. “You gonna act like a bunch of girls and let your buddy hang?!” Again, silence. “You call these assholes your friends?” he asked Richie, chuckling. “These aren’t your friends! They don’t care about you!” This from a full-grown adult who would in an hour’s time respond to a 14-year-old’s tearful retelling of how a mother of three children invited him to see how many of his fingers he could fit inside her at one time by saying, “Aw, come on! Don’t be a baby about it! Count yourself lucky — you’re a man! So how many fingers was it?”

“Yes, sir, I did it,” said Philhower, looking at the ground, while another officer approached to read him his rights.

“How about you?” said Von Schmidt, moving down the line and going nose to nose with Danny, who was beginning to hyperventilate.

“Yeah,” exhaled Danny, “I did it.”

Von Schmidt took another step to the left. “And how about you?”

I nodded and stared at my shoes.

“You?” said Von Schmidt, stopping in front of my big brother.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Jeff, shrugging his shoulders slightly and shaking his head in bewilderment.

“All right, get lost!” ordered Von Schmidt.

Watching Jeff casually round the corner with his hands in his pockets, not a care in the world, we all learned, perhaps too late, how the truth is sometimes way too important to be limited by the facts.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.