The Court Stacks the Deck

Affirmative action has opened doors for disadvantaged minorities and made this a fairer, more equal society. The Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts apparently wants no more of that. Shutterstock

Shutterstock

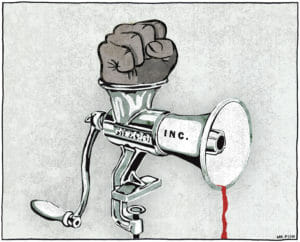

Affirmative action has opened doors for disadvantaged minorities and made this a fairer, more equal society. The Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts apparently wants no more of that.

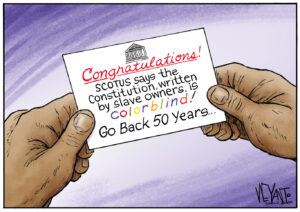

This week’s big ruling — upholding a Michigan state constitutional amendment that bans public universities from considering race in admissions — claims to leave affirmative action alive, if on life support. But the court’s opinion, ignoring precedent and denying reality, can only be read as an invitation for other states to follow suit.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s thundering dissent should be required reading. She sees what the court is doing and isn’t afraid to call out her colleagues on the disingenuous claim that the ruling in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action is limited in scope. It has implications that go beyond college admissions to other areas, such as voting rights, where majorities seek to trample minority rights.

By “rights,” I mean not affirmative action but the principle, upheld repeatedly by the court, that the political process should be a level playing field. In Michigan, with the high court’s blessing, anyone who wants to advocate for affirmative action is at a disadvantage. Instead of banning the policy outright — which would at least be honest — the court paints it with a bull’s-eye and strips it of defenses.

The case involves the University of Michigan, my alma mater, by the way, which has spent nearly two decades trying to defend taking race into account, as one of many factors, in deciding admissions.

The university is governed by an elected board of regents, some of whose members have campaigned on their views for or against affirmative action. Opponents of what they call “racial preferences” tried but failed to elect enough like-minded regents to end the practice, so they proposed an amendment to the state Constitution that says Michigan’s public universities “shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin.” Voters approved the measure in 2006 by a wide margin.

This may sound reasonable, even admirable, but here’s the problem: With the amendment, voters changed the political process in a way that unfairly burdens racial minorities.

There was, after all, an existing process for influencing the university’s admissions policies. You could lobby the regents. You could run ads to pressure the board. You could campaign for board candidates who shared your views. You could run to become a regent yourself.

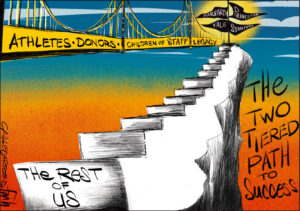

You can still do any of these things if you want to want to influence the university’s admissions policies in any other way — if you want, say, more places reserved for “legacy” applicants who are the sons and daughters of alumni. But if you want to influence the board in favor of race-sensitive admissions, you have only one option: an onerous, expensive and almost surely futile attempt to amend the state Constitution yet again.

As Sotomayor writes, “The effect … is that a white graduate of a public Michigan university who wishes to pass his historical privilege on to his children may freely lobby the board of that university in favor of an expanded legacy admissions policy, whereas a black Michigander who was denied the opportunity to attend that very university cannot lobby the board in favor of a policy that might give his children a chance that he never had.”

If stacking the deck in this manner is acceptable in university admissions, why not in voting rights? Sotomayor’s dissent recounts the long history of attempts by majorities to change the political process in order to deny racial and ethnic minorities the chance to achieve their goals. The court has recognized a duty to protect the process rights of minorities — until now, apparently.

Once she dispenses with the other side’s legal arguments, the court’s first Hispanic justice — Sotomayor is of Puerto Rican descent — gets personal.

Race matters, she writes, “for reasons that really are only skin deep, that cannot be discussed any other way, and that cannot be wished away.”

She goes on, “Race matters to a young man’s view of society when he spends his teenage years watching others tense up as he passes, no matter the neighborhood where he grew up. Race matters to a young woman’s sense of self when she states her hometown, and then is pressed, ‘No, where are you really from?’ … Race matters because of the slights, the snickers, the silent judgments that reinforce that most crippling of thoughts: ‘I do not belong here.'”

To young people of color, the Roberts court replies: Maybe you don’t.

Eugene Robinson’s e-mail address is eugenerobinson(at)washpost.com.

© 2014, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.