The Controversial Legacy Behind Chris Christie’s Budget Claims

The New Jersey governor closed budget gaps by borrowing, shifting money from trust funds and paring back tax credits.

By Cezary Podkul, ProPublica, and Allan Sloan, The Washington Post

This story was co-published by ProPublica and The Washington Post.

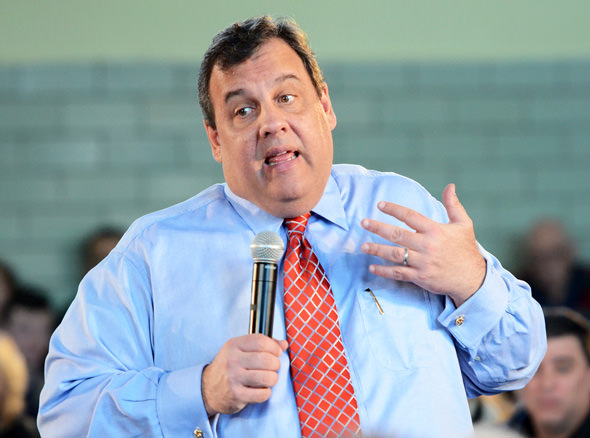

TRENTON, N.J. – In his “tell-it-like-it-is” tour of New Hampshire this week, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie said the country needs a president who isn’t afraid to be honest about the tough fiscal choices needed to overhaul entitlement programs and keep deficits from ravaging the Treasury.

He pointed to progress in his own state.

“When I took over as governor of New Jersey, my predecessor, Governor Jon Corzine, had left us a mess – record deficits … the highest top tax rates and overall tax burden in America,” the Republican governor said. “People said New Jersey could never be turned around. But we took action.”

Christie’s remarks, laced with blunt criticism of President Obama’s record, were reflective of the image that he has spent years cultivating – that of a bipartisan broker dedicated to fixing long-standing fiscal problems once and for all. That image is also one that would serve as the centerpiece of a 2016 run by Christie for the White House.

An examination of Christie’s record by The Washington Post and ProPublica, however, paints a more complicated story of his fiscal stewardship of one of the biggest state budgets. It’s a story that will probably face far greater scrutiny should he declare himself a presidential candidate.

Although Christie has balanced the state budget for five years – as required by New Jersey law – he has resorted to many of the financial maneuvers used by some of his predecessors: reducing state payments to pension plans, shifting money out of trust funds dedicated for specific purposes and borrowing to patch chronic budget gaps.

And despite overcoming a multibillion-dollar deficit that Corzine left him, Christie has seen the nation’s three biggest rating agencies downgrade New Jersey’s credit a total of nine times on his watch. Only Illinois ranks lower.

In New Hampshire, Christie laid out ambitious proposals to sustain entitlement programs in the face of looming deficits.

On Social Security, for instance, he has billed his proposed changes – which include phasing out benefits for retirees with $80,000 or more in other income – as an effort to protect the program for future seniors who need it most. In New Jersey, however, his policies have shifted financial hardships to less-wealthy residents.

He has both pared back income tax credits for the working poor and reduced or deferred subsidies that help lower- and middle-class homeowners cope with the highest per capita property taxes in the nation.

Christie’s economic legacy is not yet final. He had success early on with a high-profile deal that sharply reduced the state’s chronic pension shortfalls. Now he’s pushing an even more ambitious plan that would require unions and municipalities to take over financial responsibilities currently borne by the state, dramatically increasing their own risks.

Christie declined to be interviewed for this article. His spokesman, Kevin Roberts, said, “The governor confronted an almost unprecedented set of fiscal challenges when he took office, and he wrapped his arms around that and found solutions that didn’t involve raising taxes on already-overburdened New Jerseyans.”

Roberts didn’t dispute a list of one-time budget fixes compiled by ProPublica and The Post.

“If you’re not going to raise taxes, then it means that you have to work within the constraints that you have, and that means making choices,” Roberts said. “And that’s what we’ve done.”

There’s no doubt New Jersey was a fiscal basket case when Christie took office in 2010. The financial crisis had slashed income tax receipts from state residents, including high earners who worked on Wall Street. Employers were cutting payrolls. And the decline of Atlantic City’s gambling business was gathering speed.

“Fiscal responsibility in New Jersey can no longer wait,” Christie said just a few days after his election.

One of his first major steps in 2010 was to cancel a proposed $8.7 billion rail tunnel under the Hudson River to New York City, a move that brought him national prominence.

The planned rail tunnel had its problems – critics noted that it terminated more than 20 stories underground. Proponents said it had the potential to make New Jersey a more desirable place to live, raise property values and spur development.

Christie said he nixed the tunnel as a matter of fiscal responsibility, arguing that cost overruns would have cost the state billions more than initially projected. The federal government had promised $4.5 billion toward the cost and was so eager to get a “shovel-ready” project going to create jobs that it offered cheap loans to cover possible overruns. Christie’s office said the offer was insufficient.

The decision allowed Christie to restructure the budget in a manner that has become his signature. In this case, he shifted $3 billion in highway tolls and other money originally earmarked for the tunnel to plug various budget holes – the biggest one-time fix of his administration.

Records show that $1.25 billion in Jersey Turnpike and Garden State Parkway toll increases enacted to cover New Jersey’s tunnel contribution made its way into the coffers of the state Transportation Trust Fund. And as New Jersey continued to miss targets for tax revenues, the money was soon transferred to the state’s operating budget.

The shift caused collateral damage: The Transportation Trust Fund had to borrow $1 billion more than would otherwise have been the case, according to the nonpartisan New Jersey Office of Legislative Services. The fund is approaching its credit limit and is now routinely described as “insolvent” or “going broke,” including by Christie’s transportation commissioner.

State Treasurer Andrew Sidamon-Eristoff, a Christie appointee, said in an interview that the toll money transfer was appropriate because it replaced state subsidies to New Jersey Transit, the state-owned rail and bus carrier. And while the trust fund had to borrow more, he said, it did so more responsibly than past administrations by avoiding risky debt structures such as “capital appreciation bonds.” These bonds require no regular payments and let interest pile up for years or decades until a huge payment comes due at maturity.

Critics say the shuffle broke a Christie pledge to use “pay as you go” funding rather than debt for transportation needs.

“He was going to reduce borrowing, but he didn’t,” said Martin Robins, who headed the cross-Hudson tunnel project from 1994 to 1998. “This debt is going to be around for decades.”

The remainder of Christie’s tunnel windfall came from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates bridges, tunnels, a subway and airports in the region. The authority had agreed to cover $3 billion of tunnel expenses. After the cancellation, it decided to give Christie $1.8 billion.

Now that money is being used to refurbish New Jersey’s Pulaski Skyway, a rusty old elevated roadway, and two other projects that Christie’s budget would otherwise have had to cover.

The Port Authority, meanwhile, is again considering a cross-Hudson tunnel among various options to boost badly needed commuting and freight capacity.

New Jersey is renowned for its high property taxes – the largest state tax that many residents pay. For years before Christie took office, property taxes had risen rapidly.

“Today, that comes to an end,” Christie declared in May 2010, when he proposed limiting the annual increase that municipalities and school districts can impose.

The annual 2 percent cap, with exceptions for items such as health care and pension costs, was enacted that year.

At a recent town hall in Somerville, Christie said his property tax cap has made the state a more affordable place to live. Property taxes had been rising by about 7 percent a year versus less than 2 percent under the cap, Christie said – a statement he has frequently made.

That claim, however, does not take into account Christie’s moves to help his budget by cutting and delaying a popular property tax offset. That offset, known as New Jersey’s Homestead Benefit, helps seniors and disabled people with less than $150,000 in annual income and people below 65 with less than $75,000.

Thanks to repeat deferrals, nothing was paid out in 2014, compared with $2 billion at the program’s peak in 2007, when more than 1.7 million households received rebates.

Accounting for those cuts, New Jersey’s net residential property taxes have risen about 4 percent a year under Christie, more than the governor has claimed.

Sidamon-Eristoff acknowledged delaying payouts under the Homestead Benefit to save cash. But he blamed the bulk of the reduction in the program on eligibility restrictions enacted by Corzine.

The precise reason for the delays might not matter to New Jersey homeowners who have benefited from the program. Many, though, are painfully aware of how their tax break has shrunk over the past few years.

Angelo Brito, a 72-year-old homeowner in Kearny, an industrial town across the Hudson from New York City, said he and his wife get by on $60 a month in food stamps and $21,000 a year in Social Security. The property tax bill for their modest home is nearly $8,000.

The Homestead Benefit is supposed to lessen the burden, but the last benefit Brito received, $663, was in August 2013 for the 2011 tax year. His 2012 benefit isn’t scheduled to be paid until next month.

“You get a little Social Security check, everything goes for the taxes,” Brito said.

Though Christie has stuck by his pledge not to raise income tax rates, he has reduced New Jersey’s earned income tax credit, which offsets taxes and pays cash refunds to the working poor.

The decrease, to 20 percent of the federal credit from the previous 25 percent, cut the maximum benefit by $300 to about $1,200, affecting about 500,000 low-income families.

Roberts, Christie’s spokesman, said the governor offered three times to restore the 25 percent credit, most recently as part of a proposed deal with Democrats to keep a minimum wage increase provision out of the state’s constitution. The Democrats declined, and voters approved the wage boost in 2013.

The property tax cap and another Christie budget fix have had other consequences.

At the same time the cap took effect, Christie’s administration slashed municipal aid by about 17 percent, to $1.3 billion a year – a boon for the state budget, but one that has put the squeeze on many of New Jersey’s cities.

In Kearny, for example, Mayor Alberto Santos said he’s stuck cutting services “to the bone” to make ends meet.

Santos, a Democrat, said Kearny now has only one fire truck in service rather than the minimum of two the city needs. Although he gave Christie credit for new rules to help curb police and fire pay, he said the governor has given mayors like him few tools to stay inside the 2 percent cap.

“The continual shifting of the cost of government services to the property homeowner has continued even under his administration,” Santos said.

Sidamon-Eristoff said Christie administration policies had “imposed long-overdue discipline on local government units” and that the governor’s reforms to pensions and health benefits provided cost savings that more than offset the reduced aid.

Christie hasn’t shied from another budget fix his predecessors embraced: reducing pension payments for public employees.

In 2011, he negotiated a groundbreaking package of reforms with Democrats and their union allies. It eliminated annual cost-of-living increases for pensioners, reduced future benefits and increased contributions from current workers. The compromise was hailed as a model fix.

As part of the bargain, Christie agreed to substantially raise New Jersey’s contributions to the funds. But last year, he refused to make the full payment, saying the state didn’t have the money.

That embarrassed Democrats who had agreed to the benefit cuts and made future cooperation more difficult. It also triggered union lawsuits that resulted in a judge’s ruling in February that requires an additional $1.57 billion pension payment by June 30. The state is appealing.

In a February budget address, Christie proclaimed that by June 2016, he will have “contributed more in total to the pension system than any other administration in New Jersey history.”

“By nearly double,” he added.

That estimate, however, fails to count a $2.75 billion pension contribution made during the administration of Republican Gov. Christine Todd Whitman in 1997, according to an analysis by ProPublica and The Post. Overall, Whitman contributed $3.7 billion to the pension funds. Christie has contributed $2.2 billion thus far and promised another $2 billion by June 30 of next year.

The $4.2 billion projected Christie total is far from “nearly double” Whitman’s $3.7 billion.

“He’s right to say he inherited a problem; I just wish he’d get the facts right,” Whitman said in an interview.

Sidamon-Eristoff says that the $2.75 billion shouldn’t count because it came from proceeds of a state pension bond issue and therefore isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison. In fact, the bonds have been a bad deal for the state because they carry interest rates above what the funds have earned.

Nevertheless, the borrowing helped the pension funds, because the $2.75 billion and 18 years of returns have added about $9.5 billion to the funds’ assets, according to a Post/ProPublica estimate based on state treasury numbers.

Like some of his other fixes, Christie’s latest proposal to control the cost of public employee pensions and health care also would shift the state’s financial risks to other parties.

Christie has eagerly embraced a proposal, put forward by a commission he appointed, that would freeze current pensions and provide less-generous “cash balance” plans for new retirees. Its success depends on achieving large reductions in health-care costs for public employees and retirees. Unions, cities and school districts would take on obligations the state now covers.

Much of the presumed health care savings would flow to the state, which would use the money to make annual payments to the frozen funds.

The state’s obligation would be locked into the state constitution under a measure Christie wants on the November ballot. The crux of the proposal is that unions – which would take over managing the funds – would be responsible for any future pension shortfalls.

“If we’re able to get this off the books, our credit rating will go up,” Christie said at his Somerville town hall meeting.

Two days after his budget address, Moody’s credit analysts took stock of the judge’s ruling on pensions as well as Christie’s proposed fix.

The agency gave New Jersey a negative credit outlook. And on Thursday, it completed the process by dealing the state its ninth downgrade.

Disclosure: Co-author Allan Sloan owns New Jersey Transportation Trust Fund bonds. The market value of those bonds is determined largely by interest rates.

Email Allan Sloan at [email protected].

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for their newsletter.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.