The Case You Go to Law School For

Meet the woman who spent 22 years working alone and without pay to set free a convicted serial killer who, in all likelihood, is innocent.

Looking for the latest outrage from the American justice system after the execution of Troy Davis? Meet Bobby Joe Maxwell and get to know his lawyer, Pasadena attorney Verna Wefald.

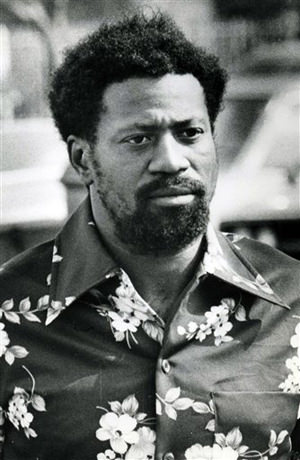

Now 63 and in his 32nd year behind bars, serving a sentence of life without the possibility of parole, Maxwell is an accused serial killer once known as the Skid Row Stabber of Los Angeles. Arrested in 1979, Maxwell’s trial was delayed until late 1983 by legal motions and wrangling over the publicity rights to his life story. When it finally commenced, the trial lasted nine months and was the stuff of L.A. noir, orchestrated against a media frenzy that portrayed Maxwell as a shadowy Satanist responsible for the deaths of at least 10 homeless men. The problem is, in all likelihood, he’s innocent.

Wefald, 58, runs a solo law practice specializing in criminal appeals. She operates on a shoestring budget primarily drawn from meagerly paid court appointments. I’ve known her since we were colleagues briefly at the Los Angeles branch of the State Public Defender’s office before the branch was closed down for budget reasons in the early ’90s, and I’ve often wondered how and why she does what she does. For the past 22 years, Wefald has represented Maxwell before state and federal courts, often for free, insisting to anyone who would listen that her client wasn’t guilty, that he’d been framed by perjured testimony and prosecutorial misconduct committed by the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office.

It’s never been easy. Wefald recently told me that when she first signed on to defend Maxwell on appeal in 1989, “I was young and thought this was the kind of case you went to law school for. About 10 years into it, I wished I had never gone.”

After another decade of failure, including a heartbreaking rejection by the California Supreme Court, Wefald finally won over a panel of three judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit who didn’t seem to realize that it had become politically unwise to side with criminal defendants challenging their convictions, especially when the defendants are black and poor. In November, the panel granted Maxwell a writ of habeas corpus, ordering him to be released or retried. The judges found that Maxwell’s conviction was based largely on trial testimony delivered by a notoriously unreliable and since deceased jailhouse informant named Sidney Storch—a transplanted New Yorker and a heroin addict who had a long and public history of dishonesty, starting with his discharge from the U.S. Army in 1964 for being a habitual liar.

Unbeknownst to the defense at the time, the DA had worked out a secret deal with Storch. In return for testifying that Maxwell had confessed his guilt while the two were briefly housed together at the county jail, the prosecution agreed to shorten Storch’s prison term on multiple counts of forgery and drug offenses from 36 months to 16. The prosecution also withheld from the defense Storch’s extensive record as a government informant.

Rather than accept the 9th Circuit’s ruling, the state of California has petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the circuit. The petition is pending. Should the high court accept the petition and issue a substantive decision in the case, Maxwell will almost assuredly spend the rest of his natural life in prison as there is next to no possibility that John Roberts and his activist conservative associates will rule in Maxwell’s favor. And even if the Supreme Court rejects the state’s petition and sends the case back to the original trial court and the district attorney, Maxwell won’t be out of the woods as the DA has indicated that he will retry Maxwell without Storch’s recorded testimony from the first go-round.

Even with Storch’s testimony in the original case, the prosecution was able to convict Maxwell of only two counts of murder. The trial jury hung on five murder charges and returned not-guilty verdicts on three.

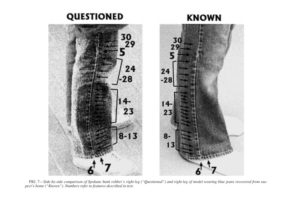

Storch was the prosecution’s prize witness and without him, the case against Maxwell was and remains extraordinarily weak. As the 9th Circuit’s opinion notes, “ … The prosecution’s best physical evidence linking Maxwell to any of the crime scenes was a palm print on a public bench found near the body of one of the victims. The bench, however, was located in an area Maxwell [who was himself a transient] frequented, and the prosecution was unable to isolate the age of the print.” There were also some muddy footprints found at one crime scene, and, although the prosecution’s forensic expert testified that they were consistent with Maxwell’s shoes, he also conceded they were too indistinct to prove anything.

Nor did the stabbings on Skid Row stop after Maxwell was taken into custody. Indeed, the court prevented the prosecution from claiming as much at trial.

So why not after so many years correct such an obvious injustice? The answer lies partly in the history of Maxwell’s particular case and partly in the general degeneration of the American criminal justice system into a game of might makes right.

Back in 1979, when Maxwell was arrested, Los Angeles was a city in fear, gripped by a surge in violent crime that had seen the murder rate skyrocket 84 percent over the course of the decade. At the same time, the city was rocked by the rise of criminal gangs — the Bloods, the Crips and the Mexican Mafia, among many others — fueled by years of official neglect of the area’s ghettos and an epidemic in the use of crack cocaine.Just a year before Maxwell was put on trial, the DA had secured a conviction in the Hillside Strangler case. The office was on a roll and on a mission. It wasn’t about to reconsider Maxwell’s guilt, even with the threadbare evidence against him.

By the time Wefald agreed to take on his case, Maxwell had languished for five years without appellate representation. From the start, it was a lonely job. Since Maxwell’s jury had voted to spare him the death penalty, Wefald had no ready-made network of like-minded lawyers and activist abolitionist groups like Death Penalty Focus that often provide assistance and moral support in capital cases. Many of Wefald’s peers, myself included, thought there was little that could be done for Maxwell short of an outright reversal of his conviction. And that, we thought, bordered on fantasy.

But there was a small opening in the darkness. In 1988, another notorious jailhouse informant—Leslie White—whose relations with the DA had soured, went public. White demonstrated to sheriff’s deputies and later on CBS’ “60 Minutes” how he and other informants like Storch were able to obtain confidential information and then fabricate confessions of fellow prisoners.

White’s revelations prompted the state’s attorney general to appoint a special counsel and convene a grand jury investigation. Over the next two years, the grand jury heard under oath from more than 120 witnesses, including White and Storch, who was looking for leniency after he had been caught lying in another unrelated criminal case. In all, the defense bar estimated that White, Storch and other informants had trumped up testimony in Los Angeles County over a 10-year period against some 225 defendants accused of murder and other serious felonies. Storch’s signature method, used to “book” high-profile defendants, was to gain proximity while in jail and then, as the 9th Circuit noted, “get information about the case from the media, usually a newspaper, and then call the district attorney or law enforcement and offer to testify.”

Wefald seized on the grand jury’s final report, released in 1990. She pursued Storch, who had wound up imprisoned in New York, where he died in 1992. She pursued his long-lost estranged brother, who confirmed Storch’s sordid background and character. She also tracked down and interviewed dozens of law enforcement officials, probation officers and prison inmates who knew Storch and his modus operandi and were willing to talk.

As Wefald’s work moved forward, other lawyers, investigators and researchers began looking into the misuse of jailhouse informants, not only in Los Angeles and California, but nationwide. What they found was ugly and chilling—that testimony from snitches was the leading cause of wrongful convictions in death penalty cases in the U.S., and that in California, 20 percent of wrongful convictions stemmed from perjured informant statements. Spurred by such findings, this past August, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a bill that bans judges and juries from convicting defendants based solely on the uncorroborated testimony of jailhouse informants.

Given the current hard-right ideological orientation of the U.S. Supreme Court and the rigid posture of the L.A. County District Attorney, the new legislation and all the horrifying revelations about jailhouse informants will be of little avail to Bobby Joe Maxwell. The Supreme Court used to be a place where good cases went for vindication. Not anymore.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.