The Californian Ideology Personified

The Silicon Valley mashup of countercultural, libertarian and neoliberal values is on full display in the memoir of John Perry Barlow, who knew Timothy Leary, Jerry Garcia, Steve Jobs, Dick Cheney and JFK Jr. Crown Archetype

Crown Archetype

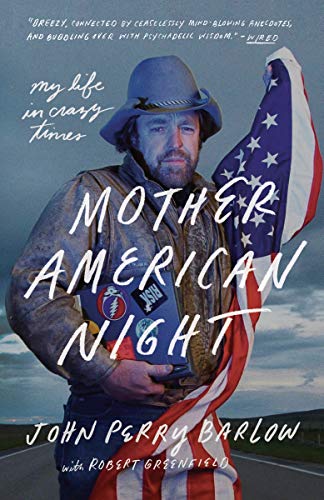

“Mother American Night: My Life in Crazy Times”

A book by John Perry Barlow with Robert Greenfield

John Perry Barlow, who died this year at age 70, led an extraordinary life. The son of a Wyoming rancher and politician, Barlow befriended a young Bob Weir at a Colorado boarding school and met Timothy Leary while studying in Connecticut. Soon after the Grateful Dead became popular, Barlow reconnected with Weir and wrote several songs with him. He took over the family ranch, married and fathered three daughters. He was also active in Wyoming politics; in the late 1970s, he coordinated Dick Cheney’s congressional campaign in Sublette County.

Eventually Barlow contributed to dozens of Grateful Dead songs. Only lyricist Robert Hunter, who entered the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame with the band, outproduced him. The Dead’s reputation, especially in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, opened other doors for Barlow. Through the Dead, for example, he developed an interest in Apple computers and eventually came to know Steve Jobs. An early internet enthusiast, he also wrote for Wired magazine, which was described at the time as “the Rolling Stone of technology.”

In 1990, Barlow cofounded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which defends civil liberties in the digital world. He also popularized the term cyberspace, which he lifted from “Neuromancer,” the 1984 science fiction novel. In 1996, the year after the Grateful Dead dissolved, he wrote “The Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” a libertarian manifesto that reached a broad online audience. For these and other efforts, fellow EFF co-founder Mitch Kapor dubbed Barlow “the uncrowned poet laureate of cyberspace.”

Barlow’s memoir, “Mother American Night: My Life in Crazy Times,” guides readers through his various worlds. Author Robert Greenfield—whose previous works include biographies of Leary, Jerry Garcia, and Owsley Stanley—also receives a writing credit. Greenfield’s assistance was almost certainly indispensable. As the memoir notes, Barlow failed to deliver on two early book contracts and was in poor health for the last several years of his life.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Mother American Night” at Google Books.

Barlow’s cast of characters is broad and diverse, and the tone is conversational, even homespun, despite his increasingly cosmopolitan life. As in many real conversations, little effort is made to smooth out inconsistencies or explore paradoxes. On one page, Barlow prides himself on not judging people; on the next, he says the best way to judge people is by their children. He describes Leary as the least spiritual person he knew, then suggests that no one since Jesus Christ introduced more people to the spiritual dimension. Rather than probe or reconcile these claims, Barlow turns to the next topic.

Occasionally he slows down to showcase a romance or friendship. As expected, he features Weir, Leary, Jobs and Grateful Dead guitarist Garcia. He also showcases his relationship with John F. Kennedy Jr., who spent a summer on Barlow’s ranch as a teenager. Barlow says he taught Kennedy how to fly and later maintained a “psychoactive” friendship with him. Along the way, we hear about Cheney, Alan Simpson, Owsley Stanley, Andy Warhol, Daryl Hannah and a host of other notables in entertainment, politics and technology.

For Barlow, these relationships are badges of honor, even when his anecdotes don’t show him to advantage. The passages about Garcia, for example, suggest not only a prickly relationship, but also that Garcia had his number. Barlow says that Hannah, who was Kennedy’s girlfriend at the time, didn’t trust him. “I am not an untrustworthy person at all,” Barlow says, “but for some reason people often feel that I might be, especially if they are not terribly sophisticated.”

Barlow didn’t seem to fit a type, but he exemplifies what two British sociologists call the Californian Ideology, a term they coined in the mid-1990s to describe the Silicon Valley mashup of countercultural, libertarian and neoliberal values. That blend is on full display in the memoir. Barlow’s Grateful Dead connection and long-standing interest in psychedelics established his standing among hippies. He was also active in the Stewart Brand strain of the Bay Area counterculture, which produced the Whole Earth Catalog, Wired, and the WELL, an early virtual community co-founded by Brand in 1985.

Barlow’s politics emerge most clearly in his discussion of Simpson, a family friend and former senator from Wyoming. “For many years, I described myself as an Al Simpson Republican,” he writes. “He was a conservationist, a fiscal conservative, and a social liberal.” Barlow regrets Simpson’s role in the GOP effort to destroy Anita Hill’s reputation during the Clarence Thomas hearings. Simpson, he says, “just got caught up in the mob, as one sometimes can.” Simpson’s key contribution to American public life may have been his co-chairmanship of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, whose primary goal was federal debt reduction. For his part, Simpson never tired of warning Americans that popular social insurance programs would burden future generations.

After his 18-year Senate stint, Simpson taught at Harvard, where he directed the Institute of Politics. “I’d actually had something to do with helping him get the appointment,” Barlow writes, “and the two of us had a fine time there.” It was during this period, he says, that he had three dates with Anita Hill. He was also a fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, which was founded in 1998. That affiliation burnished Barlow’s credentials as an expert on digital culture.

If Barlow’s politics grew out of his Wyoming experience, he also mapped his libertarian views onto the emergent cyberculture. It’s no accident that the word “frontier” figures in the name of the organization he co-founded. In his memoir and elsewhere, Barlow compares the internet to the American West of the 19th century. In particular, the internet was “vast, unmapped, culturally and legally ambiguous … and up for grabs.” It was also, he claims, “a perfect breeding ground for both outlaws and new ideas about liberty.” It’s a rich simile, but not only for the reasons Barlow cites. In the 19th century, massive government investments fueled westward expansion. Once settled, the American West was quickly dominated by corporate monopolies, especially the railroads. Likewise, cyberspace flowed not from private-sector visionaries but from federally funded research that quickly spawned today’s monopolies, most notably Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon.

The EFF, which Barlow calls “one of the major achievements of my life,” has reflected his libertarianism since its inception. It is quick to join legal fights over government surveillance and crackdowns on free expression. Julian Assange and Edward Snowden, both of whom appear in the memoir, received EFF support. The watchdogs are more docile, however, when Silicon Valley corporations routinely breach user privacy for profit. April Glaser, a former EFF employee, has wondered why the digital crusaders were keen to challenge the surveillance state but less concerned about reining in Facebook after the Cambridge Analytica affair. Yet that posture is consistent with the Californian Ideology that Barlow personifies.

Both in the memoir and elsewhere, Barlow is given to sweeping pronouncements rather than policy specifics. Kapor once noted his colleague’s need for the occasional “hyberbolectomy.” The memoir, too, is dotted with stretchers. Barlow claims that samurai founded a Japanese firm that acquired (and then shut down) a biotech company he backed. My online check showed that the firm was founded toward the end of the samurai period, but I saw no mention of samurai. Yet Barlow barrels on, describing the firm’s corporate culture today in samurai terms.

Barlow also claims that Garcia “always had overwhelming personal charisma. Saint Thomas Aquinas and the original Scholastics defined charisma as unwarranted grace. Unearned, undeserved, completely gratuitous grace. So that was yet another burden he had to carry with him, both onstage and off.” It is unclear from this passage how Garcia’s charisma was a burden, or what the theological reference adds to an otherwise routine observation. (Charisms were thought to be gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as piety, not connected to divine grace as such or personal charisma in the modern sense.) As with the samurai, perhaps, Barlow thought it sounded cooler to name-check Aquinas.

The memoir frequently lapses into cliche. Simpson, we learn, would have won re-election to the Senate unless found in bed with a live man or a dead woman. For Jobs, “design was something that went all the way to the core, and he knew there weren’t many people who understood that. It’s hard to say where that came from, but what I do know for certain is that we will never see his like again.”

Although Barlow is forthcoming about his love life, he is relatively tight-lipped about his marriage to Elaine Parker Barlow. “Even though I was not completely faithful to Elaine during this period,” he says, “it was always my strong intention to stay married to her. So I made sure that whatever I did was a one-night stand that would not come back to affect our marriage.” They divorced in 1995. Recounting his time with Leary and his wife Barbara, Barlow says, “Tim basically gave me permission to be her lover.” Basically? We also learn that Barlow and Grateful Dead manager Jon McIntire tried to have sex; that effort failed somehow, and they resumed their friendship. Barlow’s most serious romance was with a married woman—he was also married at the time—but she died unexpectedly. Readers may wonder why the memoir includes the text of his eulogy or the fact that it went viral.

There is something deeply American about Barlow. Leary introduced him as the most American person he knew. “It was intended to be both a compliment and an insult,” Barlow recalls. “Here’s Barlow. He’s an American.” The book’s cover photograph plays to that image. We see him in high cowboy drag, literally wrapped in an American flag, with a laptop tucked under his arm. Barlow’s unremitting self-invention, thinly masked by his studied nonchalance, is nothing if not American. He concludes his memoir by reassuring readers of its unprecedented veracity. “To the best of my knowledge,” he writes, “a completely true work of nonfiction has never been written before. But now at long last it finally has.”

He was an American, all right—perhaps more Buffalo Bill Cody than Mark Twain.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.